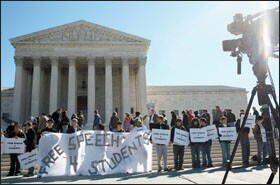

The U.S. Supreme Court appeared sharply divided last week on whether a student’s banner proclaiming “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” outside an Alaska high school was protected speech or a message that school authorities could suppress because it ran counter to their policies against the promotion of illegal drugs.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer seemed to capture the court’s concerns as it heard arguments in Morse v. Frederick (Case No. 06-278) on March 19.

“It’s pretty hard to run a school where kids go around at public events publicly making a joke out of drugs,” Justice Breyer told Douglas K. Mertz, the lawyer representing former high school student Joseph Frederick, whose suspension for 10 days in 2002 stemmed from the incident.

Justice Breyer said he worried that if he took the student’s side, “we’ll suddenly see people testing limits all over the place in the high schools. But a rule that’s against your side may really limit people’s rights on free speech. That’s what I’m struggling with.”

Kenneth W. Starr, the lawyer representing Deborah Morse, who was the principal of Juneau-Douglas High School, in Juneau, at the time of the incident, argued that Mr. Frederick’s 14-foot banner was an assault on the district’s anti-drug policies.

“Illegal drugs and the glorification of drug culture are profoundly serious problems for our nation,” Mr. Starr told the justices.

When his turn came, Mr. Mertz, the Juneau lawyer representing Mr. Frederick, told the justices: “This is a case about free speech. It is not a case about drugs.”

Was It Disruptive?

The arguments came nearly two decades after the Supreme Court upheld the right of secondary school students to wear black armbands to protest the Vietnam War. In that landmark 1969 decision in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the court upheld such political expression as long as school was not substantially disrupted.

Based on the oral arguments, the decision in the Alaska case is likely to be a close one. There appeared to be some sentiment among the justices for carving out an exception to Tinker’s protections when the student speech in question runs counter to school anti-drug policies or when it advocates violent or any illegal activity.

Another possibility is that the justices could decide that Mr. Frederick’s banner was not student speech at all—but protected public speech—because it occurred off campus and he had never arrived at school that day before he showed up at the parade at which he and other students displayed the banner.

But through most of the argument, the justices treated the case as one involving school speech.

Several justices wanted to know from Mr. Starr just what about Mr. Frederick’s banner was disruptive to his high school, since it was displayed across the street from the school during a corporate-sponsored event to celebrate the carrying of the Olympic torch. The event was attended by members of the general public in addition to Juneau-Douglas High students, who had been dismissed from classes for the event. (“Rights at Stake in Free-Speech Case,” March 14, 2007.)

“I can understand if he unfurled the banner in a classroom that it would be disruptive, but what did it disrupt on the sidewalk?” Justice David H. Souter asked.

The banner disrupted the school’s educational mission, Mr. Starr said.

Justice Souter, who was the most aggressively pro-free-speech member of the court in his questioning, replied: “Then if that’s the rule, the school can make any rule … on any subject restrictive of speech, and if anyone violates it, the result is, on your reasoning, it’s disruptive under Tinker.”

Mr. Starr, a former U.S. solicitor general and the independent counsel who investigated the Whitewater matter during the Clinton administration, said the school board has considerable discretion to identify the educational mission and “to prevent disruption of that mission, and this is disruptive of the mission.”

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Antonin Scalia seemed most receptive to that argument—with the chief justice suggesting that even if students were engaging in political speech, which the court traditionally gives the highest level of protection, it could be considered disruptive of that mission.

“I mean, why is it that the classroom ought to be a forum for political debate simply because the students want to put that on their agenda?” Chief Justice Roberts asked. “Presumably, the teacher’s agenda is a little bit different and includes things like teaching Shakespeare or the Pythagorean theorem, and just because political speech is on the student’s agenda, I’m not sure that it makes sense to read Tinker so broadly as to include protection of … that speech.”

But Mr. Starr resisted such a blatant curbing of student speech, noting that the Supreme Court has not aimed “even in the public school setting” to “cast a pall of orthodoxy to prevent the discussion of ideas.”

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy asked about students who expressed “a particular view on a political issue—No Child Left Behind, or foreign intervention, and so forth?”

What is needed, Mr. Starr replied, is “restoration, frankly, of greater school discretion” in deciding whether the speech is disruptive or not, with less intervention by the federal courts.

A ‘Disturbing Argument’

Representing the Bush administration on the side of the 5,063-student Juneau school district, Deputy U.S. Solicitor General Edwin S. Kneedler said the court should be guided by two of its later student-speech decisions that reined in Tinker.

Those are Bethel School District v. Fraser, a 1986 case that upheld the discipline of a student who had made a sexually suggestive speech at a student assembly, and Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, the 1988 ruling that clarified the authority of school administrators over speech that could be construed as school-sponsored, such as in a school newspaper that is part of the school’s academic program.

“A school does not have to tolerate a message that is inconsistent with its basic educational” mission, Mr. Kneedler said.

“I find that a very, very disturbing argument,” said Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., because under such an interpretation, schools “can define their educational mission so broadly that they can suppress all sorts of political speech and speech expressing fundamental values of the students, under the banner of getting rid of speech that’s inconsistent with their educational mission.”

Justice Alito’s comments echoed concerns by conservative religious-advocacy groups, which in an unlikely alliance have joined with the American Civil Liberties Union in supporting Mr. Frederick in the case because they fear the effects the case may have on student religious expression in public schools.

As a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit, in Philadelphia, Justice Alito wrote several opinions backing students’ rights to religious expression in public schools, including one that struck down a school district’s anti-harassment policy because it prohibited “a substantial amount of speech that would not constitute actionable harassment under either federal or state law.”

Mr. Mertz argued that, based on Tinker, a school district could control a student’s speech only if it caused “a substantial disruption of what the school is trying to achieve legitimately, whether it’s a classroom lesson or a lesson on drug use.”

Mr. Mertz said, for example, that the wearing of a “nondisruptive pin” by a student would have to be tolerated. However, he said, authorities would not have to tolerate a student’s interruption of an anti-drug presentation.

Qualified-Immunity Issue

The one issue on which the justices seemed to be in agreement was that Ms. Morse, the principal of Juneau-Douglas High in 2002, deserved immunity from personal liability in the lawsuit that Mr. Frederick filed against her.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, in San Francisco, held that Ms. Morse was not immune from the lawsuit because the violation of the student’s rights was clear. No amount for Ms. Morse’s damages has been set.

The student was “certainly willing to negotiate a minimum settlement,” Mr. Mertz said.

“But there’s a broader issue of whether principals and teachers around the country have to fear that they’re going to have to pay out of their personal pocket whenever they take actions pursuant to established board policies that they think are necessary to promote the school’s educational mission,” Chief Justice Roberts said.

Justice Souter suggested that Ms. Morse could not have been expected to know she was violating Mr. Frederick’s rights when she disciplined him for a banner that she interpreted as violating the school’s policies against promoting illegal drugs.

“We’ve been debating this in this courtroom for going on an hour, and it seems to me, however you come out, there is reasonable debate,” Justice Souter said to Mr. Mertz. Should the principal have known, “even in the calm deliberative atmosphere of the school later, what the correct answer is?”

A decision is expected by the end of the court’s term in June.