Perhaps more than any other part of schooling, making a school feel safe, welcoming, and uplifting to students really hinges on the principal.

It’s the principal, after all, who sets the tone for a school’s culture by his or her everyday actions and interactions with teachers, families, and students, and who sets into motion the core elements of school climate work: Social-emotional learning, youth voice and leadership programs, and restorative practices.

Now principals face the added challenge of doing that across remote and hybrid learning systems, not just for in-person learning.

While the logistics are trickier, experts say, the core tenets of school climate work are unchanged. 69��ý will still need to feel safe and connected to their schools even when they are only there a few days a week—or only connected through technology.

“Whether or not you feel safe, whether or not you feel engaged and connected and cared about, by the people who are teaching you and working around you, and are experiencing some level of challenge and support to meet the challenge—those are things that matter whether you are learning virtually or in school, whether you’re in the middle of a pandemic, or on vacation,” said David Osher, vice president and institute fellow at the American Institutes for Research, who consults with school districts on school climate efforts.

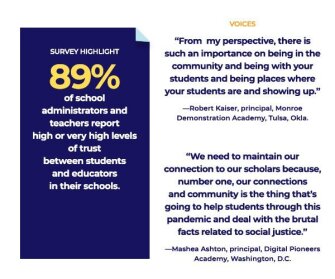

In fact, principals say the uncertainties of COVID-19 and its stress on families, added to the ongoing protests against systemic racism unleashed this summer, make school climate work more critical than ever.

“We needed to maintain our connection to our scholars because, number one, our connections and community is the thing that’s going to help students through this pandemic and deal with the brutal facts related to social justice,” said Mashea Ashton, the principal of Digital Pioneers Academy, a computer-science charter middle school in the District of Columbia that serves an almost entirely Black student population. “And number two, it sends the message that they can still learn, even in the most crazy of circumstances.”

Education Week spoke with Ashton, Osher, and two other leaders who have committed to improving school climate even as COVID-19 reshapes the fundamentals of American schooling in 2020-21—and beyond. Here are five recommendations for principals.

Stay visible, communicate religiously, and enlist parent feedback.

Visibility is one of the most powerful tools in the principal’s climate arsenal: Greeting students as they enter the building, being a presence in the hallways, and being available to parents.

“The principal’s first job is to make everyone feel safe, and the way you make people feel safe is being really present and really listening to people. It’s the equivalent of being at the bus stop every morning,” said Suki Steinhauser, the chief executive officer of Communities in 69��ý of Central Texas. Her group works with 96 schools in the state, offering both case management to individual students and whole-school efforts to improve school climate.

As schools put some or all teaching online, that will mean going beyond emails, web updates, or the newsletter sent home every Thursday. At Digital Pioneers, Ashton calls it KLR, or building a “known, loved, and respected” community shared equally by parents and students.

So far, the school has done virtual home visits with about 80 percent of its students. It’s also put in place an adviser structure in which each adult in the school checks on about eight families twice a week to share academic and behavioral progress and answer any questions they have.

“We ask them, ‘What are your hopes and dreams? What are things you’re worried about being virtual?’ We want our scholars to be respected, and we want our adults to be respected,” she said.

So far this year, these engagement strategies have yielded a 95 percent attendance rate, defined as attending all three main synchronous blocks of instruction, in part. Ashton attributes that in part being clear about the format and expectations for remote learning.

“The number one feedback from families that participated is that one thing that is going well is communication, which is incredibly important,” Ashton said. “We’ve been very consistent with building the known, loved, respected community.”

During the final weeks of the spring semester, Ashton hosted several open-ended community forums on Zoom. Some parents were tentative at first, unsure if administrators were really interested in hearing their unvarnished feedback. But over time, Ashton said, they have been more comfortable sharing feedback. Some of the forums have included more than 200 parents and community members.

“Now our parents are our role models,” Ashton says. “They just jump right in, and so [the newer parents] are like … ‘Oh, that’s how we do it?’ ”

It can sometimes be challenging to have such an open forum. Parents found the first week of the 2020-21 school year rocky and let Ashton know in no uncertain terms. But, she said, “it’s very easy to listen when things are good. It is most important to listen when things are tough, and that is part of our values, and we’ve done it as part of our culture.”

Steinhauser, too, says COVID-19 has highlighted the power of parent engagement as a necessary component in climate work in the schools her group has worked in. She saw a different level of engagement from those parents who had regular, personal contact with a principal or staff member.

“We began hearing, ‘We wouldn’t have been able to make it back if you had not stayed in contact with us,’ ” she said.

For those principals in schools that have returned at least part of the time, there is also an opportunity to be visible in new ways as the school moves to unfamiliar policies, like staggered cafeteria times, one-way hallways, and or temperature checks with the school nurse.

“It’s a chance to start the day well, to be there with whoever is doing those temperature checks,” Steinhauser said.

Focus on the essentials in data collection.

Most school-climate efforts begin with some regular way of surveying students about how they feel about schooling, particularly about their relationships with their teachers and with their peers. Not only do these tools allow for a cycle of feedback and revision, but they also allow schools to set a baseline and track progress over time.

There are literally dozens of freely available tools, including some, like the U.S. Department of Education-created , that come with web-based platforms that can be easily used in a remote-learning context.

The problem is that most of those tools have been designed and validated in regular, in-person environments. So when a survey asks a question like, “Do you feel safe at school?” principals will need to be mindful that safety in a remote-learning setting at home means something different from safety during normal school operations.

“There are items in [those surveys] right now that work, probably, and can be made to work, because you want to know whether or not they’re in a chat room [where] they feel safe, since you can have virtual bullying,” noted Osher. “Or when they’re in a Zoom class, do they feel engaged? That’s emotional engagement, cognitive engagement. And you want to know whether or not people feel that the teacher is recognizing them and responding to them,” he said.

Osher suggests principals may want to consider slimming down the number of questions on surveys, keeping them focused on engagement, relationships, and academics.

School leaders will need to be careful in how they interpret the results. It may mean establishing a new baseline, since data collected during remote learning won’t be strictly comparable with former data collections.

Create dedicated times for students to share how they’re feeling.

Ideally, school-climate efforts are woven through different content areas throughout the normal schedule. That level of coherence is harder to achieve in remote learning, or in a hybrid setting, where different groups of students are attending in person on different days.

One solution is to put dedicated time on the school calendar for advisory periods or check-ins with students that help to build connections with teachers and peers that undergird school climate.

At Digital Pioneers Academy, “community meeting” kicks off each morning. It’s the only course alongside math and literacy that students receive every day. Every community meeting includes two adults to about 25 students.

“Community meeting is probably the most joyful part of the day for many of our scholars. For the first two weeks of school, they researched and selected class names, after colleges and universities with strong computer-science programs, to create a community they feel a part of,” Ashton said.

Now that the year is well under way, community meeting has settled into a reassuring routine. The first 15 minutes or so are “warm welcome,” a greeting and a warmup question to get students in the mindset of learning. There’s a quick two- to three-minute mindfulness activity, like a breathing exercise. And there’s “temperature check,” where students respond in the chat box on how they’re feeling, using a color-coded system that corresponds to moods like high energy and pleasantness, to feeling down or despairing.

During community meeting, teachers can open a private breakout room to chat with students who are struggling for whatever reason, heading off anything that could get in the way of the day’s academic lessons.

Meet families where they are.

While the pandemic has exposed deep inequities in public education, it has also challenged the notion that some parents aren’t invested in the quality of schooling. Instead, parents have been at the forefront, demanding more synchronous instruction and higher-quality learning activities, and school leaders are often more attuned to the challenges that they face with work, child care, and transportation.

With those realities in mind, some principals are setting up innovative ways to make it easier for working families to connect to their schools. In Tulsa, Okla., the principal of Monroe Demonstration Academy, a middle school serving some 850 students, has led an innovative approach to bringing school to where families actually live.

The school serves many students who live in four nearby public housing developments. With the help of the Tulsa Housing Authority, the school now offers “satellite office hours” each Monday through Thursday at one of the complexes, staffed by Principal Robert Kaiser, assistant principals, tech support staff, and the dean of students.

Many parents stop by with tech-related questions about the district-distributed learning devices, others to collect distance learning supplements, others to apply for aid programs or scholarships. Sometimes, parents and students stop by just to say hello.

“From my perspective, there is such an importance on being in the community and being with your students and being places where your students are and showing up,” said Kaiser. “Our goal here at Monroe is to continue to build trust, to build consistency, and showing up for our students and families.”

Distribute leadership—for staff and for students.

Now is not the time to lone-wolf leadership, the experts said. Not only does distributing leadership make processes more efficient and new policies less burdensome, it can help build buy-in for the new schedules and duties.

“You distribute leadership for at least three reasons. The more people who are involved, if it’s an efficient process, the more perspectives you have to make whatever you do better. The second is because of the fact that you want to distribute the burden. Third is that you want buy-in, and part of buy-in is people being cheerleaders,” said Osher.

“In a situation where people’s bandwidth is so stripped, I might say to my colleagues, ‘I would love to have you involved in this process. Do you want to be involved? If you don’t, I still want you to give me input. It’s important for me for you to really want this as well,’” he added.

Kaiser’s school in Tulsa has instituted what it’s calling alignment teams, which will operate like work groups to tackle problems. The teams will focus on climate and culture, professional learning, and wellness, among others. Teachers from different content areas will apply to join the committees; eventually, so will community members. The idea is to avoid the common problem where just one person is viewed as the sole point person on an initiative, Kaiser said.

For all of its disruptions, the pandemic also affords the chance to give new leadership opportunities to a group that’s often overlooked: students. For example, they can help to inform school climate survey data by conducting some qualitative, follow-up research with peers, and then formally weighing in on the results to the school leadership team.

“I would try to find some way of mentoring and collaborating with young people where they could help do data collection virtually,” Osher said. “I think you probably get higher-quality work if it’s youth-to-youth, and higher response rates. There’s a whole literature on youth-led participatory research, and I think that young people often like doing it.”

“I admire principals who deputize the students to carry the water, perhaps with a leadership council of students or a leadership group of students,” Steinhauser said. “There are always kids who show resilience or leadership qualities who haven’t been noticed or had an opportunity to lead.”