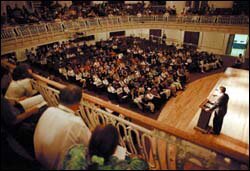

With a subtle drawl and a preacher’s cadence, Eric J. Smith is talking about beliefs. “What do we believe?” he prompts. “WHAT DO WE BELIEVE?!” His amplified voice booms through the high school auditorium, where some 600 educators, mostly principals and other administrators, are gathered on a Wednesday morning in mid-August.

“All children can learn,” he says, lowering his voice. “Do you believe that? Anyone doesn’t believe that?”

The Anne Arundel County school district’s one- day leadership conference, held each summer, always kicks off with an address by the superintendent. Typically, it’s a brief welcome-back speech. The previous schools chief rarely spoke for more than five minutes. But Smith, who took over the superintendency here six weeks earlier, delivers a soul- searching, 45-minute sermon. He speaks in terms of moral obligations about teaching all kids to read by the end of 3rd grade and preparing all students for college.

“All children can learn,” he repeats, slowly chopping his hand through the air as he speaks. “The critical difference on whether they do or don’t is us.”

|

To his critics, Eric J. Smith, the superintendent of Anne Arundel County, Md., public schools, is uncompromising, which is also what his fans say. |

It’s the first time many in the assembly have been in the same room with Smith, and there’s a range of reactions. Brenda Hurbanis, a middle school principal and 30-year veteran of the district, puts herself in the category of those thinking, “Hallelujah! Here’s someone to move us forward.” Others, she says, wondered “What are we in for here?” And many withheld judgment. But no one left the meeting doubting that the 2002-03 school year would bring big changes to the 75,000-student Maryland district.

Big change is exactly what Smith was hired to make. Ten years ago, Anne Arundel County’s overall results on state assessments placed it sixth among Maryland’s 24 school systems. Now it ranks 17th. The county’s 120 schools reflect a classic bell curve. Income level and race are the best predictors of performance. So after the last superintendent announced plans to retire, the school board set out to find someone who could narrow the achievement gap while raising the bar for everyone.

Smith is one of the few superintendents in the country to have accomplished both feats in a large, urban system. Under his watch, from 1996 to 2002, the 100,000-student Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C., district saw significant improvement among all subgroups of students, and the achievement gap between black and white students began to close. Smith’s formula for success included expanding preschool, standardizing curricula, and pushing more students to take the most rigorous high school courses.

Anne Arundel lured Smith with a salary of $197,000, plus about another $100,000 in benefits and potential bonuses. “The pool for this kind of talent is shallow,” says school board member Carlesa Finney. “We were determined to get the best for our children.”

In the 12 months after his arrival, the district will undergo more change than it went through in the previous decade. But it won’t come easy. For the first time, Smith, 53, is operating in a state with strong unions. He faces new budget constraints. And most of all, many in the local school community aren’t yet convinced of the need for major upheaval.

Although he has an evangelical side, Smith’s mind is scientific. He’s most comfortable when pondering test scores and the levers that can yield organizational change. He’s a constant wellspring of ideas. The joke in Charlotte was that no one wanted to ride the elevator with Smith, because the people who did were sure to be assigned three new projects by the time they reached their floors.

|

Smith quickly switches gears as he finishes a call to return to a meeting with leaders of the local teachers’ union. |

To his critics, he’s uncompromising, which is also what his fans say. Nora Carr, who served as his communications director in North Carolina, says Smith’s strong determination makes him stand out. “There are many superintendents who know what the problems are,” she says. “But they’re not willing to take it head on, and roll about with it, and get muddied and bloodied.”

Smith is also highly ambitious. He was in his 20s, teaching middle school in Florida, when he made up his mind to become a superintendent. His office walls are plastered with awards, including one from the Council of the Great City 69��ý naming him the country’s top urban superintendent. He intends to make a national mark in Anne Arundel by seeing whether what worked in Charlotte and similar places can produce results in a mostly suburban, albeit diverse, school system. For his fast pace, he makes no apologies.

“Superintendents who intend to help a system become stronger aren’t given a lot of time in America,” he says in an interview. “So you have a relatively brief window of opportunity to work.”

He starts the job in July 2002 by demanding data. After a few days of number-crunching, his top administrators hand him a data book with each school’s reading and mathematics scores, for each grade, broken down by race and gender. It confirms the wide disparities in Anne Arundel, which encompasses farm land, subsidized housing, blue-collar towns, and some of the region’s most affluent enclaves along the inlets of the Chesapeake Bay. At the 4th grade, 63 percent of the county’s white students scored at or above the 50th percentile on the reading portion of the Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills, compared with 35 percent of black students.

|

Generous quantities of coffee help fuel Smith throughout the day. The superintendent is known for leaving a trail of coffee mugs behind him on his travels throughout the county. |

But Smith also sees ample room for improvement at the high end. On average, Anne Arundel is one of the wealthiest counties in Maryland, and yet in 2002 it had just eight National Merit Scholarship semifinalists, an honor bestowed on students based on their scores on the pretest for college admissions known as the PSAT. Two nearby Maryland counties— Howard and Montgomery—had 30 and 118 semifinalists, respectively. As Smith repeatedly tells staff members: “We need to raise the floor and the ceiling.”

The data prompt Smith to make some early executive decisions. He decrees that all 9th, 10th, and 11th graders will take the PSAT in October. The results, he hopes, will identify more students capable of Advanced Placement coursework. In the past, a mix of student initiative and teacher recommendations largely determined who took AP classes.

He orders far more dramatic changes in the lower grades. In late July, he mandates that starting this school year, 14 low-performing elementary schools will adopt two commercial, highly scripted instructional programs: Saxon Math and the Open Court reading curriculum. The decree means training some 300 educators in a whole new way to teach in the waning days of summer. “If they can’t read by the end of 3rd grade, you might as well go out of business,” Smith says. “And there’s no time to lose. It’s just like a crisis.”

As it soon becomes clear, the whole system is in store for major retooling. At a September school board meeting, Smith presents eight performance targets, including the pledge that by June 2007, 85 percent of students in all tested grades will meet the state’s standard of “proficient” performance. By comparison, just 48 percent of 5th graders achieved satisfactory scores in math in 2001. He also promises to narrow the achievement gap between all racial and ethnic groups to within 10 percentage points in four years. At the meeting, board member Tony Spencer recounts what he told a reporter who asked whether “we were going to kick Montgomery County’s butt.”

The board member’s reply: “We’re going to kick butt all over the country.”

Smith peels off his suit jacket and hangs it on the back of a chair on a mid-November day. Behind the seat that he takes at one end of a long table hangs a neatly framed article about him from The Washington Post. Before him sit eight executive-staff members, including his assistant and associate superintendents, his governmental liaison and business manager, and his public information officer. Together, they are the nerve center of Smith’s campaign to restructure the district’s operations. “OK, let’s get started,” he says.

|

Janet S. Owens, Anne Arundel’s county executive, meets with Smith to discuss the school district’s budget. The county government ends up giving the schools half the increase he seeks. |

The topic is next year’s budget. The superintendent is planning for a host of new initiatives, including dramatic increases in AP offerings, expansion of Open Court to all elementary schools, and new magnet high schools based on the rigorous International Baccalaureate program. He also wants to buy $12 million worth of new textbooks. He complains that the current textbooks lack coherence, and that some classes have no books.

At the same time, he wants the budget’s bottom line to reflect one of the smallest increases in recent years. In part, that’s because he knows the dollars are scarce. In Anne Arundel—where the County Council must ultimately approve the district’s budget—public finances are constrained by a strict cap on local tax revenue approved by voters in 1992. But Smith also wants to make a statement about fiscal responsibility his first year. He’s told his senior staff to set priorities for all spending based on the performance targets approved by the board in September.

“How we capture the message of the budget—the public image around the budget— is going to be key,” Smith says at the meeting.

Aside from the superintendent, only one person in the room is new to the district. Smith hasn’t felt the need to clean house. In interviews, he says he demands loyalty and high-quality work from his top staff members, and so far they’re delivering. They’re also well-steeped in local politics and culture. One associate superintendent has been with the system for 30 years; another once was a budget official with the county government. Smith presses all of them for advice on how to move his agenda.

Meanwhile, he’s coaching them on new ways of doing business. His biggest tool for changing the way the central office works is “project management.” Adapted from the business world, project management assigns each new project to a senior administrator, who helps pull together people from relevant departments, such as human resources, information technology, and purchasing.

Part of what project management aims to do is speed things up. As in most districts, planning in Anne Arundel had long been a more insular process, says Greg Nourse, the associate superintendent for business and management services. If the department of instruction had an idea, it would form its own study committee, then pass its recommendation on to other offices to determine cost and feasibility. “It would just be, here’s this thing we want to do, and then a whole other group of people would have to take a look,” Nourse says.

In Anne Arundel, the process creates eight working groups. Each drafts a “project charter,” including specific objectives, lists of interim steps to be carried out, and deadlines. A charter on improving reading and writing, for example, says exactly when new materials must be ordered, when teacher trainers must be hired, and when professional-development days must be scheduled.

In Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Smith didn’t begin using project-management until his third year. His Anne Arundel team picks it up in a matter of months. “We’re doing more on implementation this year than I’ve done in my history,” he says.

It also takes only a few months for Smith to run into his first major controversy. At issue is the scheduling of courses at the middle and high schools. Smith wants consistency in the daily schedules, of which there are now two variations at each level. More importantly, he wants high schoolers to have more chances to take high-level courses, like AP. But to ensure that they’re well prepared for those courses, he wants middle schools to spend more time on the core subjects of language arts and math. Lacking money to extend the school day, he has to divide up what time students do have differently.

|

Making public appearances goes with the job. Smith greets students and parents at the awards program for a science and engineering fair. The same night, he goes to see a school musical. |

“The real question for me is can we come up with a platform that gives me the capacity to do what we need to do,” Smith tells two board members one afternoon.

He hands the puzzle to an advisory group of principals. What they propose is that each day, students take four 86-minute classes—instead of six 50-minute ones— while rotating through a schedule in which they take certain classes one day, and others the next. Over the course of a year, the result at the high school level would be more courses, but less time spent in each. The rotation suggested for middle schools would boost time spent on math and language arts, while reducing the time for art, physical education, and foreign languages.

The superintendent knows he’s in for a fight. Anne Arundel’s last schools chief attempted a somewhat similar change at just the middle school level the previous year, and some parents were so upset that they formed the Coalition for Balanced Excellence in Education. Their successful lobbying forced the district in 2001 to adopt a compromise in which each school wound up choosing its own schedule. The main complaint of the CBEEs, as the group came to be called, was that the change marked an excessive narrowing of the curriculum.

Community pressure mounts as word of the scheduling proposals spreads through the newspapers and on the CBEEs’ Web site. It comes to a head at a pair of public hearings on the issue in early December. They stretch late into the night as parents, educators, and students voice their views—mostly in opposition. Teachers object that the changes would increase their workloads. With less time per course, some students say they worry about dumbing-down their AP classes.

At the hearings, Smith takes notes and looks each speaker in the eye, even the teacher who calls his administration a “totalitarian regime.” In the end, he adopts the proposals almost exactly as originally drafted. When a group of parents later asks the school board to override the decision, the panel gives Smith its unanimous support.

But some board members offer a critique of Smith’s handling of the issue. As she bundles up against a bitterly cold night after one hearing, Carlesa Finney suggests the superintendent could have lessened the public vitriol by seeking community input earlier. “I hope,” she says, “that he’s learned some more things from this experience that allow him, not to slow down so much, as some people have said, but to do things in a more proactive way that engages a community that is used to being engaged.”

Smith isn’t sure why the parents have come. Three members of a local citizens’ advisory group have asked to meet with him at the central office on a rainy Monday afternoon in May. They’re from the town of Severna Park, one of the county’s highest-income areas and a hotbed of parent activism where Smith has encountered some of his strongest resistance. The superintendent sits down with the group in a small conference room. The first to speak is Rob Leahy, an active member of the organization, who wears an American-flag pin on his a navy-blue jacket.

|

At the Center of Applied Technology-South, Smith visits with students in a cosmetology class. He wants all students, including those enrolled in vocational courses, to be prepared for college. |

“It seems to be that we’ve got this reputation of always fighting things,” says Leahy. “How can we help you to move things forward?”

“That means a lot,” says Smith.

They offer him an olive branch. They know that many in their community still oppose some of Smith’s initiatives. But they also want to maintain good relations with his administration. Steering clear of items of major debate, they suggest an issue on which they might be able to work together. For years, the parents have wanted a later starting time for their high school, which opens at 7:17 a.m.—too early, they say, for teenage brains to be in learning mode. “I’d be willing to entertain that,” Smith says.

“It is so important,” he adds, “that we figure out ways to disagree, and still come back and fight the big fight together.”

The meeting is one of a few bright spots after several months of hard work. By now, teachers are being trained in how to hold students’ attention through the longer class periods that will begin in the fall. Central-office employees have chosen some 100 new reading and math books for what will be one of the largest single textbook purchases that they’ve ever made. More than 20 Anne Arundel educators have traveled to South Carolina to learn how to implement the International Baccalaureate program, which Smith’s board gave him the go-ahead to install in two high schools.

The superintendent also finds some encouragement in new data. The district sends letters home to students who scored well on the PSAT, encouraging them to sign up for AP classes for the fall. They wind up registering for some 10,000 such courses, more than doubling the current figure. The number of black students registered jumps from 193 to 528. Results from state-mandated tests given in March show that together, the 14 elementary schools using Open Court post 4th grade reading gains that outpace the district’s as a whole.

But the picture is far from rosy. The CBEEs challenge the superintendent’s scheduling plans in a complaint to state education officials. During the war in Iraq, Smith makes the unpopular decision to cancel overseas trips for students. And after one of the region’s snowiest winters in recent decades—during which the roof of one school collapses—the district is at risk of having to make up student days by cutting into teacher-training time.

|

Running late, Smith drives through downtown Annapolis, the state capital, on his way to meetings with local police officials and a member of the Anne Arundel County Council. |

The ugliest episode involves a series of racist incidents at a county high school. Someone spray-paints “Niggers Die” in a stairwell, and neo-Nazi materials are taped to lockers. Smith has his staff work closely with the police, who arrest five students at the majority-white school on charges of harassment and disruption of school activities. He tells one of his senior administrators to begin planning initiatives to improve relations among students districtwide.

“69��ý seem to be so much of what we are in America,” he says, “and superintendents are asked to manage a great deal of the spinoff from all this stuff.”

By now, though, Smith’s biggest worry is the budget. The painstaking planning process begun early in the fall yields a $644 million total budget proposal that includes $8.5 million for Smith’s new initiatives. It also gives teachers the 3 percent pay hike called for in their contract. And the $22 million increase it requests from the county represents a 6 percent hike, modest compared with other years. The feat is accomplished, in part, by postponing the replacement of computers and by redeploying some educators who hold districtwide positions to fill openings at schools.

The school board approves the plan without major changes, but it’s another story when it goes on to the county. A severe drop in state tax revenues leads the county executive to advocate freezing the salaries of all county workers. When the dust settles, and the entire County Council has voted on Smith’s budget, he’s left with half the increase he asked for—enough for his new programs, but not for any wage hikes.

Incensed, teachers begin picketing. Some stage work-to-rule protests, in which they refuse any duties not in their contract. At one point, a flier turns up threatening a “chalk out” during upcoming state testing. Smith readies an army of substitute teachers and central-office staff members to fill in should there be such sickouts. He holds three forums to hear teachers’ concerns, and gets an earful. The educators bring signs protesting “More work, less pay!” and “Too much, too fast!”

What aggrieves them is adjusting to so many new ventures without any more compensation—not even increases for additional years of experience. “There has never been this much change, that’s for sure,” says Steve Korpon, a high school science teacher. “Morale is about as low as I’ve ever seen it.”

The furor puts Smith in a bind. He knows that a districtwide work-to-rule protest would jeopardize all that he wants to put in place next year. He can go back into his budget and carve out money for the pay increases, but he doesn’t want to sacrifice any of his major initiatives. “I can’t see myself advocating: ‘Don’t buy kids books—let’s pay the people,’ ” he says in an interview. “That can’t come out of my mouth.”

He offers a partial fix. Smith leaves the core of his agenda intact, but trims around the edges. He decides to give the PSAT in two grades, instead of three. He keeps the expansion of Advanced Placement, but scales back related efforts to tutor students who need an extra push to succeed in challenging classes. And instead of picking up the tab for AP exams, as he did this year, he shifts the burden back to the students. He also cuts 11 more districtwide positions.

|

It’s nearly 10 p.m. by the time Smith winds up a public hearing on proposed changes to school schedules. Complaints dominate the three-hour meeting. |

The revisions give teachers their longevity increases, but not the 3 percent raise. Work-to-rule stops at some of the schools that had engaged in the job action. Sheila M. Finlayson, the president of the Teachers Association of Anne Arundel County, an affiliate of the National Education Association, pledges to keep the pressure on. She plans to push for concessions with the district, possibly cutting a few teacher work days off next year’s schedule. “It’s the first step,” she says of Smith’s revised budget. “If it hadn’t happened, no one would want to come work in Anne Arundel County.”

The school board accepts Smith’s new, $633 million budget at a mid-June meeting. But other bumps in the road still loom. State budget estimates are still a moving target. So when Smith reaches the last school day of his first year, his biggest challenge has yet to be fully resolved. There is no sigh of relief, only more work.

On a beastly hot day in late June, administrators and teacher leaders file into an air-conditioned high school auditorium. It’s the same hall where many got their first glimpse of Eric Smith 11 months earlier. Always impatient for change, the superintendent has moved Anne Arundel’s leadership conference from the end of summer to the beginning and extended it from one day to two.

“It’s been an interesting year,” Smith says as he begins his address. “Has anyone been bored?”

For nearly an hour, he talks of beliefs, sacrifice, and the power to transform student’s lives. He reads the district’s four-year performance goals. He recounts the heated debates of the past year, but maintains there’s a “quiet side” to the county that has embraced the changes.

“THE TIME IS NOW!” he insists. “We have the tools on the field. ... and we now have a choice as to how to proceed.”

Coverage of leadership issues in education—including governance, management, and labor relations—is supported by the Broad Foundation.