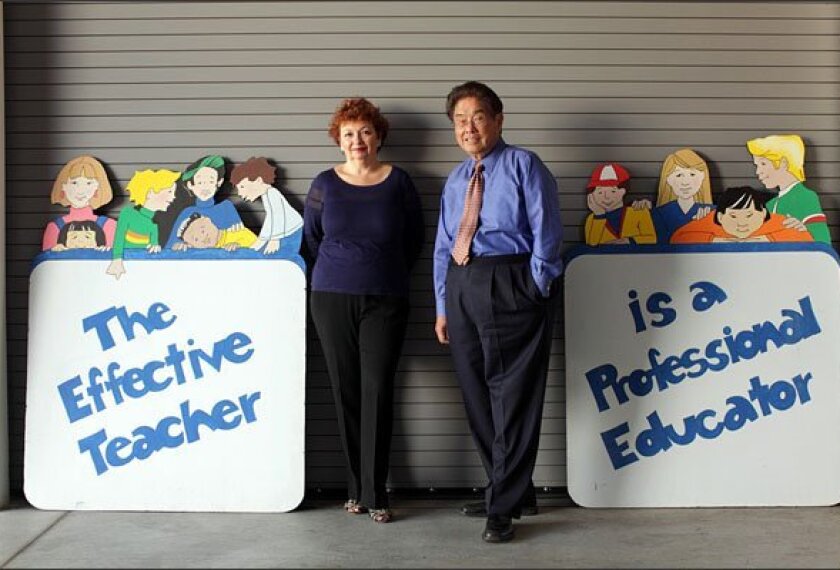

Nearly 25 years ago, Harry and Rosemary Wong, both former teachers, decided to write a how-to book on teaching based on the well-received presentations that Harry was then giving on the school professional-development circuit. The book, titled , was self-published and designed to look “like an automobile’s manual.” The Wongs didn’t expect it to make much of an impact. “We just thought we’d write a book to help teachers,” Rosemary Wong says.

What they didn’t account for was how many teachers would need the help they were offering. Since its publication in 1991, The First Days of School has sold some 3.8 million copies and has been printed in six languages. According to the Wongs, it is used as a classroom text in more than 2,000 colleges. In all likelihood, it is the most popular book on K-12 teaching in the United States—a text that every teacher seems to know. At one point early on, Harry Wong recalls, they had to start publishing it with a specialty binding because they were getting complaints from teachers who said the pages were falling out from overuse.

The Wongs, who are based in Mountain View, Calif., followed up on The First Days of School with a series of DVDs about instructional issues and have become highly sought-after speakers on teaching. For the past 10 years, they’ve also written a monthly column for Teachers.net.

The First Days of School, still their signature work, is oriented around three characteristics of effective teaching—classroom management, positive expectations, and lesson mastery. But the Wongs have become especially well known for their advice on classroom management, an area where many teachers struggle. Emphasizing teacher preparedness and the use of well-defined procedures, the Wongs’ approach to management promises educators highly concrete practices they can use to create greater order in their classrooms. But the approach has also faced criticism over the years, with some educators saying it can stifle spontaneity in classrooms and lead teachers to become overly controlling.

The Wongs have a new book on classroom management scheduled to come out later this year—titled, somewhat plainly, The Classroom Management Book. We recently talked to the couple about their advice on leading a classroom and how it applies to a new generation of teachers.

The First Days of 69��ý is one of the most well-known and frequently referred to books on teaching. Why do you think it has resonated so strongly with teachers and teacher-educators?

Harry Wong: I think the reason is really in the subtitle of the book, which is “How to Be an Effective Teacher.” We tried to give teachers very practical advice on being effective in the classroom, and a teacher’s effectiveness has been shown time and time again to have a greater impact on student achievement than any other factor. Educators get that. So we zeroed in on the three characteristics of effective teachers—classroom management, lesson mastery, and positive expectations. And what we talk about is based on the research. Years ago, I was at a conference and an education scholar named Thomas Good gave me a copy of a book he had co-written called Looking in Classrooms. It was a groundbreaking study on what makes good teachers good, and it had a major influence on how we described effective teaching. The characteristics we outlined have also been highlighted by later teaching experts like Robert Pianta of the University of Virginia and Charlotte Danielson, who’s very popular now. So you could say that the advice we give teachers, in a very easy-to-use format, has stood the test of time.

Rosemary Wong: Yes, the heart and soul of the book was distilling the research on how to be an effective teacher. We think that the strength of the book is that it shows teachers not just what to do—there are lots of books that do that—but also why you’re doing it. It combines the how and the why so that you can put these characteristics in place in your classroom in a coherent and seamless way.

Your forthcoming book, The Classroom Management Book, is billed as a companion volume to The First Days of School. What made you decide to write it and publish it now?

HW: Well, we’ve been planning to publish it for about 10 years! We just kept getting so much great material—you know, we have drawers full of examples that teachers send us of the excellent work they’re doing—that we put off finishing it. But finally we just said, “OK, let’s just put a stop to this whole charade and write the book.”

But I’ll tell you about the origins of the book. About 12 years ago, we heard about this new teacher right here in Silicon Valley named Sarah Jondahl who was apparently doing outstanding work. So we went to visit her classroom. Sure enough, we watched her teach and our jaws just dropped. She had a command of the classroom like we’ve seldom seen, and she was a brand new teacher! So we asked her how she learned to teach like this. She said that, in education school, she had taken a class on classroom management. The First Days of School was the textbook for the class and the final project was to develop a full-blown classroom-management plan, to be kept in a binder for your first teaching job. We asked her to see the binder, and she had this beautifully developed action plan full of procedures and examples. I looked at Rosemary and I said, “Oh, my goodness, here’s our next book.” That is, we want to teach people how to take that part of The First Days of School—the classroom-management part—and really come up with a detailed plan for when they walk in the classroom every day. Because classroom management isn’t something you can just do on the fly. You don’t want to go in there just hoping for the best.

RW: Yes, of the three characteristics of effective teaching we outline in The First Days of School, we feel the classroom-management part is primary. Unless you have your classroom organized for success, nothing you do is going to make any difference. You have to be organized and ready.

Why do you think so many teachers struggle with classroom management?

HW: I think the major reason is that they think it has to with discipline. Many teachers think classroom management means discipline. So what they do is they go into the classroom and put all their emphasis on discipline. They think classroom management is about crowd control or teaching kids to be quiet. But classroom management and discipline are two different things. The key word for classroom management is “do"—it’s about how you get kids to do things in the classroom. By contrast, the key word for discipline is “behave.” So with that, what you end up with is a reactive process, where the teacher teaches and then there’s some misbehavior and the teacher stops and reacts to the problem. By contrast, what we teach is how to be proactive, how to come up with a plan to prevent most of the problems from occurring.

RW: Another reason many teachers struggle with classroom management is that they just tell students what to do rather than teaching them what to do. You need to teach the procedures you want to follow and explain why, not just expect them to do whatever you say.

Right, your approach to classroom management has an emphasis on procedures and routines. Is that grounded in research?

HW: You bet. These aren’t just our ideas. We have been very much influenced by the research done on classroom management by Carolyn Evertson, who’s now at Vanderbilt University, and the late Jacob Kounin. I call Kounin the father of classroom management. In the 1970s, he noted that, in determining whether a classroom runs smoothly, it’s the teacher’s behavior, not the students’, that really counts. It’s all about what the teachers do. That was big. The most important factor he talked about was momentum—when you have a classroom that has procedures and is flowing smoothly and the kids are learning.

Can you give an example of what you mean by procedures?

HW: Sure. One of the procedures we recommend is greeting students as they enter the classroom. That immediately sets up a relationship. It shows kids that you recognize them, that you care for them. Then when the student goes into the classroom, there’s a procedure for bell work—on the east coast you call it a “do now.” The students open an assignment and get to work. So there’s no time wasted with the students waiting for the teacher to start the task. Those are just examples. You also may need procedures for how to quiet a classroom, how to have kids ask for help, how to collect and return papers, and how to manage transitions—all sorts of things that go on in the classroom. There are academic procedures as well—people never talk about them because, again, they think procedures only have to do with discipline. But you can have procedures for note-taking and how to do homework. I was big on those when I was a teacher.

RW: I like to say that if you could close your eyes and say to yourself, “This is something I’d like to have happen in my classroom,” then you need to come up with a procedure for it. The beauty of a procedure is that it saves time in the classroom, and that gives you more time to teach. But again, you can’t just tell students what the procedure is. You need to teach the procedure, and there are three basic steps to doing that. The first is to explain it. The second step is rehearsing it, physically going through the procedure and making corrections as needed. And the third is reinforcing it, which you can do by acknowledging that the procedure is being carried out correctly. Many teachers don’t do these steps or they stop after the first one, and they wonder, “How come [the students] aren’t doing it?” So it takes time and diligence. But when there are procedures in place, it’s amazing what a different atmosphere it can create in the classroom. We receive letters from teachers about this all the time. They see a new sense of orderliness and responsibility on the part of the students.

There’s been some pushback on your approach. For example, some educators say that a heavy focus on procedures can make classrooms dull and leave little space for teachers to get to know students’ individual needs and interests. How do you respond to that kind of criticism?

RW: Yes, I think that kind of criticism is mistaken. If you take the time to set procedures and routines in the classroom, you actually have more time to teach and get to know students. 69��ý automatically know what to do, so the teacher isn’t stopping all the time to scold kids or put out brush fires. When you see this working in a classroom, it’s the furthest thing from heavy-handed. Instead, there’s a sense of calm.

HW: If it seems heavy-handed, we think we know why that happens. Again, it’s because the teacher thinks this is all about discipline, so they don’t establish the procedures properly. Instead they set up consequences. We get questions on this all the time: “Dr. Wong, if the students don’t do what I’m asking, what are the consequences?” But we don’t advocate consequences or penalties, except in very limited cases. We are about establishing procedures and routines. By having a plan and setting the procedures, teachers are able to teach and enjoy their students. You don’t have to pester them or come up with rules and threats at every instance.

So do you think your work is sometimes misinterpreted?

HW: The fact that you’re asking these questions points to that! (Laughs.) But it’s the same as I said before: People misinterpret our work because they think classroom management is the same thing as discipline, and they think that’s what we’re talking about. We get questions like this from teachers all the time, essentially asking us how to crack down on kids, or looking for one-shot solutions. But that’s not what we’re talking about. We’re talking about having a plan in place with procedures that spell out what it is that you want your students to do. It’s interesting: In most areas of life, the word management is very positive—you manage a business, you manage your finances, you manage your schedule. But in education, you say classroom management, and to some people it’s a negative term—they think you’re trying to stifle kids’ growth and punish them. That’s not what we teach. We want teachers to be able create an atmosphere of consistency and mutual understanding where kids can thrive.

What should a teacher do if he or she has a student who really is disruptive and not following the procedures? That does happen.

HW: Yes, it does happen: You’re not going to succeed with every kid. But you don’t penalize them, you don’t try to coerce them. You simply teach the procedure again—as an athletic coach or music teacher might teach a particular technique. I tell teachers, “Don’t lose your cool.” You don’t want to get in a situation where you’re implementing rules and penalties all the time. Yes, there will be discipline problems in a classroom, but you won’t really reduce those problems unless you teach the students what to do. The effective teacher reteaches a procedure until it becomes a routine.

What’s your view of classroom-management systems that place a greater emphasis on social-emotional learning, with the goals, for example, of developing students’ sense of empathy and self-control?

HW: In principle, classroom management and social-emotional learning are two different things. Classroom management is meant to help you facilitate whatever approach you as a teacher choose to use. It’s not a curriculum. So if you want to use a social-emotional instructional approach, that’s great, but you still need some way to manage that approach.

RW: A number of schools that use our recommendations on effective classroom management also use Responsive Classroom, which is probably the best-known social-emotional program. So, as Harry is saying, the two can go hand in hand. But I’d like to add that we do address social-emotional factors, though we don’t always use that term. We think that an important part of social-emotional learning is giving students a sense of consistency and predictability and reliability. When you set up that consistency, it becomes a form of trust—and students appreciate that and learn best when they experience it. And they do internalize what’s expected of them, what they need to do to keep the classroom running smoothly. In this way, they become more responsible and self-directed.

Is the practice you recommend predicated on using direct instruction?

HW: No, what we’re providing is the foundation for what you want to do in the classroom. You have to have procedures. We’re all in favor of teaching whatever you want to teach—whether you want to do project-based learning or flipped classroom or technology-based instruction. But you have to have some organization to help you do what you want to do. As we say, having that structure in place can facilitate student autonomy and increase learning time.

If you were writing The First Days of School today, is there anything you would change?

RW: Well, the book is in its 4th edition, and each time there’s a revision we go back and look at the research to date to make sure that it supports the things we’re talking about. And through the years, we’ve not needed to change anything in terms of the three characteristics of effective teachers.

HW: Teaching teachers how to be effective—that’s our passion. And it’s what we’ve done for 30 years, and we haven’t changed because the research on that hasn’t changed. In this way, we are somewhat unusual. What they do in education is jump from one program to another—one fad, one philosophy, then a different one. We’re always looking for some magic bullet that will some save schools. 69��ý are drowning in what [education-reform scholar] Michael Fullan calls all these “ad hoc programs.” They jump from one to the next, and that’s not good for teachers or students. So we don’t intend to add to that trend—we know what works, we’ve seen it, and we stick to it.

OK, say I’m a teacher and I’m having a difficult time managing my class. What’s the one thing you would want me to remember?

RW: That every day is a new day in the classroom. You can always start anew, as if it’s the first day no matter how late in the year. Every single morning is a new morning in the classroom.

HW: There are three characteristics to effective teaching that we talk about in the First Days of School, and we haven’t talked about the last one, which is having positive expectations. So in that situation, I’d want you to remember that. We firmly believe that teaching is the noblest of all professions—you have the power to change your students’ lives. But you have to convince your students that they can achieve. That’s half the battle. The other half is to convince yourself that you can make a difference. We truly believe that every single teacher has the potential to run and manage a classroom and effectively deliver instruction. But you have to back up and have a plan.