Corrected: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the number of households in the study; there were 3 million.

The rate of COVID-19 infection in a school’s broader community is considered the most important factor in determining whether it is safe to return students to in-person instruction, and a new study highlights why: Even when the school doesn’t see outbreaks, students may be bringing the coronavirus home to vulnerable family members.

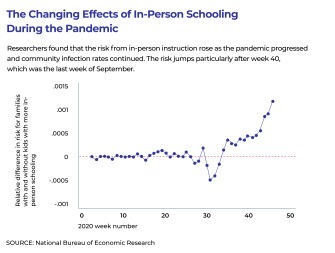

A new working paper released this week by the National Bureau of Economic Research finds that when schools have in-person instruction, families with school-age children have a higher risk of contracting the coronavirus—and the burden of that risk falls heaviest on the lowest-income communities.

“There’s a concern that when children go to school in person that they not only transmit between children,” said Christopher Whaley, policy researcher at RAND and a co-author of the study with colleagues Dena Bravata, Jonathan Cantor, and Neeraj Sood. “Your one child may transmit COVID to another child, but a potentially bigger concern is that the child may get infected and then transmit to other members of the household. And given the risk profiles of COVID, infections for older people are more risky and potentially more harmful.”

The study has not yet been peer reviewed, but offers a new perspective on how schools can affect the pandemic. Most studies of school-related COVID-19 infections have focused on outbreaks at the schools themselves, tracing the number of people who contract the virus after being in close contact with someone on campus who tests positive for the virus. The new study took a different approach, using mobile phone tracking data and private insurance data on more than 130 million observations of 3 million households in the first 46 weeks of 2020 to look at how COVID-19 infections changed when more people started going back to schools.

They found that in counties that moved to more in-person schooling, families with school-age children had a 3.2 percent higher risk of infection for every 10,000 people than those who did not have school-age children. The risk rose even more in communities with high community spread; during a spike in COVID-19 at the end of September, households with school-age children had an increase in their infection rate of 8.5 percent per 10,000 people.

That’s a significant but not a huge increase in overall risk. For comparison, a study of school mitigation practices found that lax social distancing practices can increase the risk of transmitting the virus by more than 30 percent.

While teachers have expressed concern about returning to in-person instruction, the study did not find any difference in risk for families headed by someone in the education field, as compared to those in other fields.

The study did not look at activities in individual schools, so it was not clear whether the increase in risk came from different models of in-person schooling or extracurricular activities like sports.

Risk falls hardest on poor communities

But the risk of attending in-person instruction falls disproportionately on families in high-poverty communities—communities which already see higher rates of COVID-19.

“In those counties at the bottom 25th percentile [of income], the risk of transmission was about an order of magnitude higher than in the highest-income counties,” Whaley said. “We were expecting there to be some economic differences, but not the large differences that we saw. We were surprised at how big a difference that was.”

Low-income families and communities already have been at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19, and Whaley suggested that high-poverty communities may have fewer resources to implement mitigation measures to prevent the spread of the pandemic, such as universal masking, physically distancing students, and improved ventilation in buildings. Prior studies have found school mitigation practices cost on average $55 to $442 per student.

Moreover, the study only looked at families that had private health insurance, not those who use Medicaid or Medicare. That likely means the study underestimates the risk for the highest-poverty families, Whaley said.

The results don’t mean that school and district leaders shouldn’t move students to in-person learning, the researchers cautioned. 69��ý in the lowest-income communities are also more likely to have experienced greater learning loss from school disruptions during the past year, studies have found, and students in remote classes have struggled more than those in-person.

Rather, the results suggest administrators consider the potential risk to family members—particularly for students living with grandparents or others with greater vulnerability to COVID-19—when planning for instructional modes during the pandemic.