69��ý in schools that were fully remote for most of this school year received less instructional time and were more likely to be absent and receive a failing grade than students who were attending classes in person, a new report finds.

While some teachers have pointed to some academic benefits of remote instruction, stemming from this school year. The results are particularly important given that many principals and teachers say remote learning isn’t going away any time soon.

To provide what the report deems the first look at students’ learning experiences for the majority of this school year, researchers analyzed March survey results from nationally representative samples of teachers and principals. The data provide “the clearest evidence, to date, that students were on sharply different learning pathways depending on whether their schools were mostly remote or mostly in-person for the majority of the 2020-2021 school year,” the researchers wrote.

Other research, including from the EdWeek Research Center, has shown that throughout the pandemic, students have lost out on learning time and been less engaged in their classes. Emerging evidence suggests that many students have fallen behind this year and may need to repeat a grade.

One in 5 schools were fully in person for most of the school year, while another 1 in 5 were fully remote. The rest of the schools in RAND’s sample offered a combination of in-person and remote instruction, known as a hybrid model. The fully remote schools tended to be in urban areas and serve more students of color and from low-income families.

Many of the students who learned from home for most of the school year were disadvantaged even before this year, said Julia Kaufman, a senior policy researcher at RAND and one of the authors of the report.

“When you’re comparing the outcomes of fully remote versus in person, there’s inevitably going to be a gap because there was a gap going into the school year. The question is, is that gap widening?” said Kaufman. “We do have evidence that being fully remote is not as good as being fully in person.”

Still, some teachers stress that remote learning hasn’t necessarily been all bad.

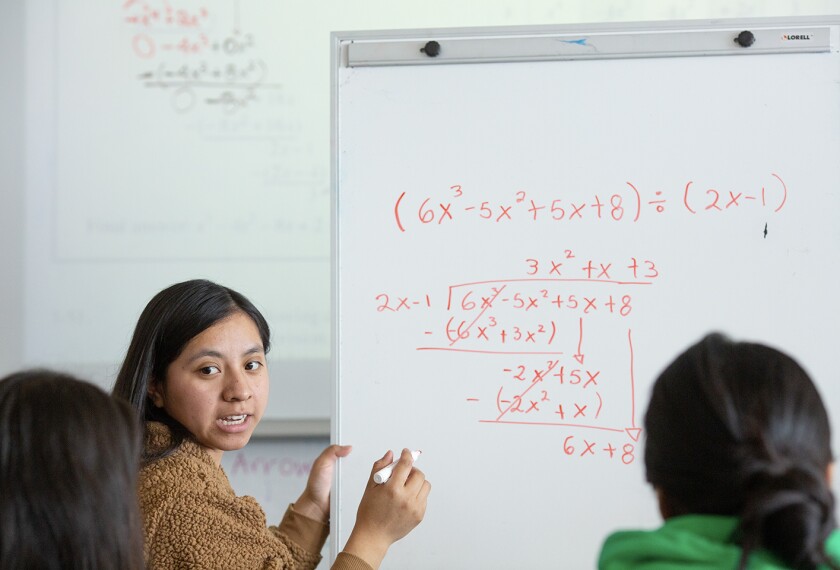

“It’s obviously portrayed pretty negatively overall throughout the country, and while not ideal, there were definitely glimmers of [success]—things I’m going to take and use next year, things we learned that may not have been on our content list,” said Megan Heine, a high school math teacher in Ankeny, Iowa, who was not involved in the RAND report. She is back in the classroom full-time this semester after periods of both remote and hybrid learning last semester, although some of her students remain fully remote. “A lot of [my students] have had a lot of success.”

Remote students get less instructional time

While RAND found that about 90 percent of fully remote schools provided at least one synchronous, or live, class per day, students learning from home still received less instructional time on average than their peers in schools. The survey found that fully remote elementary schools offered, on average, 110 fewer minutes of English/language arts, 80 fewer minutes of mathematics, and 40 fewer minutes of natural sciences than schools that were fully in person.

Kaufman said it’s possible the principals were answering with a traditional view of instruction in mind, and some remote students may be getting additional instruction that’s not captured in their responses. Even with that caveat, though, it appears remote students get less face time with their teachers, she said.

Nearly half of fully remote schools reported a shorter school day than in previous years, compared to 17 percent of fully in-person schools and 25 percent of schools offering a hybrid model.

Across the board, teachers said they covered less curriculum this year than is typical, perhaps because of time spent catching up on concepts that students missed in the previous grade. But teachers in fully remote and hybrid schools were even less likely to get through all of the content. Only 15 percent of teachers in fully remote schools and 19 percent of teachers in hybrid settings—compared with 35 percent of their counterparts in fully in-person settings—said they had covered all or nearly all of what they would cover in a more normal year.

Heine said she fell behind in her curriculum last semester, when students were only coming to school one day a week, and she hasn’t been able to catch up. Now, even though some students are back in the classroom full-time, she’s about two units behind where she would normally be.

“The inconsistency of seeing the students was definitely a factor in the content that was covered,” she said. “For hybrid students, it was very challenging to fall into a routine and structure.”

Theresa Morris, a 2nd grade teacher at Vicentia Elementary School in Corona, Calif., is teaching only students who opted to stay remote for the full school year. She said she hasn’t gotten through the same amount of material as she would have in the past—but the lessons she has taught have been richer. Since she’s working from home, she can plan meatier lessons during the time in which she would typically be waiting for students to finish assignments or managing transitions.

“I can do all of those amazing, creative, add-on lessons that I normally wouldn’t have time to do,” she said.

For example, her 2nd graders read a story about a child who was scared of a storm. One of the vocabulary words was “hurricane.” Normally, Morris said, students would learn what a hurricane is, and they’d move on.

But this year, Morris added GIFs and videos of hurricanes to her virtual presentation so students could see how the storms formed. They discussed how hurricanes turn clockwise or counterclockwise depending on which hemisphere they’re in, and then Morris asked her students to flush their toilets to see which direction the water drained.

Remote learning, she said, has given her the chance to dive deeper into what her students are most curious about, which has led to more authentic learning. And while she hasn’t been able to cover the same amount of material as she would normally, most of what she’s missed has been centered around test prep or isn’t necessary to learn in 2nd grade, she said.

“I feel like we’re not pushing these things that before we thought were so important,” Morris said. “It certainly gave me ideas about what is really needed and what is extra. We can get there when we get there, but it’s not a must-do.”

Other challenges persist for remote learners

Technology was another challenge for remote instruction, the RAND study found. Nearly half of remote teachers said their typical student experienced technical problems more than one day per week. And just 8 in 10 teachers in both remote and hybrid settings said they had internet that was fast and reliable enough to deliver instruction.

Researchers noted that the technology obstacles could have contributed to the less-rigorous instruction in remote settings. The RAND study also found that one-third of fully remote schools changed their grading policies to assign incompletes rather than failures—compared to just 6 percent of fully in-person schools.

And while principals in all settings estimated that their students’ average achievement was considerably lower this year compared with previous years, principals in remote and hybrid schools were much more likely to say their students were performing below grade level. Twenty percent of principals in fully remote schools said average student achievement in math was far below grade level this spring, compared with 8 percent of principals in hybrid schools and 4 percent of principals who were fully back on campus.

Meanwhile, teachers in the highest-poverty schools and in schools serving the most students of color—which were more likely to be fully remote for most of the school year—were more likely to report negative student outcomes, such as students not completing assignments and failing courses.

And student absenteeism is another big concern: Overall, teachers estimated that 10 percent of students were absent most school days over the past month. Teachers in remote and hybrid settings were more likely to report significant student absences.

The RAND survey asked teachers about the extra supports and interventions that were available to students this school year, and found that teachers in the highest-poverty schools and those with the most students of color said their students had significantly less access to reading specialists and one-on-one meetings with teachers, although they did have much more access to free tutoring than their peers in more affluent schools.

Kaufman said she hopes districts use their federal relief money to make sure students who need it have access to highly trained specialists.

Remote learning will stick around

Despite all the challenges, nearly half of principals whose schools have been fully remote for most of the year said they planned to offer remote instruction “to any family who wants it” in future years. Overall, a third of principals are willing to make remote learning an option.

Even so, when districts do offer families the option of remote learning, it’s often disproportionately Black and Latino families—whose communities have been hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic—who opt in. It’ll be critical to make sure any remote option going forward is rigorous and high-quality, Kaufman said.

“We know that being remote doesn’t serve all of our students well, especially those who are coming in behind,” she said. “If they’re really behind, remote will probably not help them as much as in-person [instruction].”

At least seven states have already mandated full-time, in-person learning for the 2021-22 school year, and some have restricted the amount of remote instruction school districts can offer. Just this week, the New York City mayor said students there will no longer have a remote schooling option.

Yet if given the choice, a third of teachers who have taught fully remotely for the majority of the school year would be open to continuing teaching in remote or hybrid settings, compared to just 10 percent of teachers who were in fully in-person settings.

“We suspect that teachers who have been fully remote have gotten a little more acclimated to it and have discovered that it’s not scary, it’s doable,” Kaufman said.

Indeed, Morris, the California elementary teacher, said she has applied to continue teaching remote students next year. She’s enjoyed the creativity and innovation that has happened this year.

“I have spent more time teaching and preparing and planning than any year prior, but I’ve loved it more,” she said.

Meanwhile, Heine, the Iowa math teacher, said she feels comfortable teaching remote classes and knows she could do it if she needed to. But it wouldn’t be her first choice.

“My one in-person class really does breathe life into me because I miss the student interactions,” she said. “[With remote classes], students don’t turn on their videos, they don’t even talk. For the most part every day, I’m talking to a blank screen, and that is definitely a challenge because I’m in it for the students.”