For students who have fallen years behind in math and reading, recovering that lost academic ground is a marathon, not a sprint. But it doesn’t hurt to pick up the pace.

A new study of more than 5 million K-8 students nationwide finds that students who started their school years two years or more behind their grade level were significantly more likely to catch up if educators set them aggressive learning goals that spanned more than year, rather than taking each year independently.

Though not formally peer reviewed, the study provides some of the first evidence on the effectiveness of so-called learning acceleration for students who have experienced months or years of learning disruptions during the pandemic.

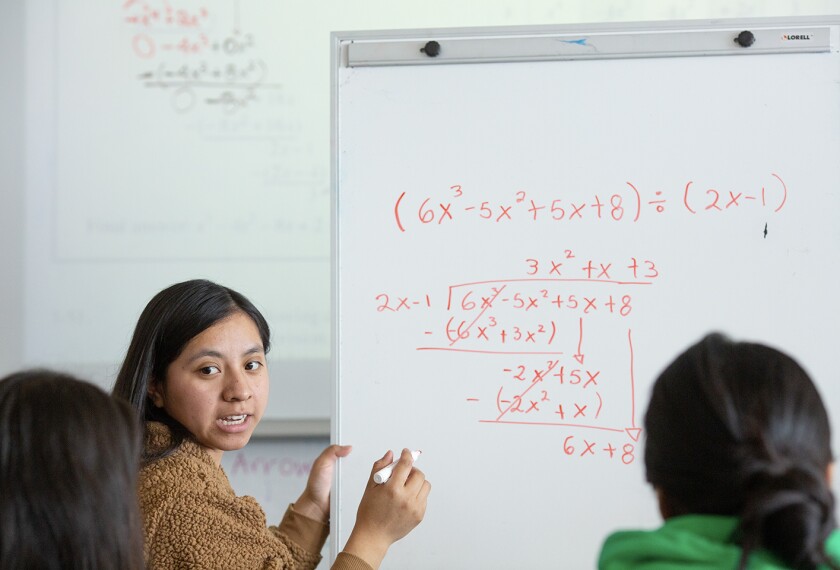

Acceleration, a concept which evolved from gifted education, focuses on teaching students grade-level content even if they have not mastered some key skills or knowledge from prior grades. In contrast to remediation, which involves filling those learning gaps before moving on to new content, a teacher using acceleration would target brief lessons to bolster the specific skills needed to understand the new material.

Researchers from the testing group Curriculum Associates analyzed data from more than 2.4 million students who completed the group’s i-Ready reading diagnostic test and more than 3 million students who completed the i-Ready math test in kindergarten through 7th grade in 2021–22 and in grades 1–8 in 2022–23.

Some of these students were taught and tested using goals based on typical academic growth for their grade. Others used what Curriculum Associates called “stretch goals,” or individualized learning plans that set students’ academic targets at a faster pace than the average pace of student learning.

The Curriculum Associates researchers found that at all grades, students who started the study performing two grade levels below their current grades were significantly more likely to reach grade level within a year if they followed the accelerated stretch goals rather than standard goals.

Typically, educators and testing systems set learning goals for students based on how much students in their grade nationwide grow academically in one school year. However, using an average pace can undermine progress for students who start the school year several grades behind, said Tyrone Holmes, the chief inclusion officer at Curriculum Associates, in a briefing about the study.

“Only students who place above average receive growth goals that have the potential to put students on a path to grade-level proficiency. Everyone else receives growth goals that if reached, will likely keep them below grade level, year after year,” he said.

“We know from previous research that students who were the furthest behind in grade-level learning before the pandemic are on the slowest trajectory to catch up to grade-level expectations,” Holmes said. “This means potentially widening achievement gaps and that those students who are already struggling are at the greatest risk of not catching up from the dire impact of these years.”

While the Curriculum Associates goals use its tests to measure student progress and set goals, the findings suggest teachers can make individual student goals more challenging by working with teachers across grades to plan multi-year goals for students who are significantly behind in core subjects.

Faster pace needed

For example, the study found that among students who started 2nd grade performing at a kindergarten reading level, 89 percent who met the accelerated goals performed at grade level by the end of the school year. By contrast, only 31 percent of those who met average-paced learning goals performed on grade level by the end of 2nd grade.

Math findings were similar: 15 percent of initially low-performing students who met standard learning goals for two years performed on grade level in math by the end of 5th grade. By contrast, 75 percent as many students following accelerated goals performed at 5th grade level in math by the end of that year.

Researchers saw smaller but still significant benefits for older students in meeting accelerated goals. For example, after two years of meeting accelerated goals, 58 percent of initially low-performing students scored on grade level by the end of 8th grade, compared to only 15 percent of their peers who had met standard goals for two years.

More challenging goals seemed to help students even if they didn’t always meet them. The study found low-performing students who followed stretch goals for two years but only met them in one year were still about 1.5 times more likely to reach grade level reading proficiency by the end of the second school year than were students who only followed average-paced goals for two years.

“We saw that even for students who do not meet their full stretch growth target even getting to only 80 percent of their stretch growth target was enough for many of these students to get to grade level,” said Kristen Huff, the Curriculum Associates vice president of assessment and research.