(This is the final post in a three-part series. You can see Part One and Part Two .)

The new question-of-the-week is:

How should teachers respond when a colleague says or does something—knowingly or unknowingly—that is racist?

In , Ixchell Reyes, Gina Laura Gullo, Cheryl Staats, Keisha Rembert, and Dr. Denita Harris offered their suggestions.

In , Dr. Angela M. Ward, Keturah Proctor, Emily Golightly, and Becky Corr contributed their commentaries.

Today, Dr. Sawsan Jaber, Denise Fawcett Facey, and Felicia Darling “wrap up” this three-part series with their thoughts.

Dealing with “racist microaggressons”

Dr. Sawsan Jaber, a global educator of 20 years in the U.S. and abroad, has a passion for facilitating critical conversations about equity. She is an OVA board director and the founder of Education Unfiltered Consulting. Follow @SJEducate:

I approach the topic of responding to the racist microaggressions of teachers and teacher colleagues with a personal lens since I feel this has been a scratched track in my CD of life that has insisted on playing over and over again. With that said, I believe that every response is contingent on the specific situation. There is no generic right answer.

What should be consistent is that whether the misconception was intentional racism or ignorance, it needs to be addressed for the sole purpose that teachers are interacting with diverse students consistently in class. Whether intentional or not, these behaviors are to the detriment of students’ feelings of belonging and inclusion in classes, and the absence of those feelings hinders the learning process, ultimately disadvantaging those students—often students from historically marginalized groups that are victims of systems that have intentionally placed them at a disadvantage.

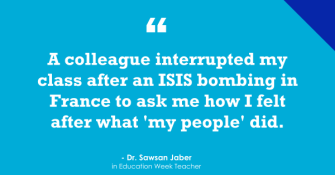

One example of a personal experience I have had was when a colleague interrupted my class after an ISIS bombing in France to ask me how I felt after what “my people” did. This incident took place in front of my students and took me by surprise. I wasn’t sure how to react since my students were witness to her racist interjection into our class lesson, so I stood there in shock.

I realized that I needed to address the issue in two ways: I needed to address it by talking to my students and addressing what was possibly the elephant in the room for some of them. Equally important, I needed to address the teacher in a professional manner making her aware that her implicit bias translated into a blatant microaggression and that her racism would not be tolerated. I began with my students by using this teachable moment to ignite conversations about bias; most of what we fear is what we do not know or don’t understand. This eventually led to a conversation about what they felt when they saw me as the only minority teacher in the district. I created an opportunity for my students to ask me anything, and they did. I worked to build trust and a culture of inquiry in my class until that point, so they were not afraid to ask questions and have critical conversations.

In dealing with the teacher, I approached her after school so that we could have a professional conversation. She became defensive and could not see the problem with her question. My next step was to discuss this with my union representative and my school principal. This teacher dealt with kids who looked like me every day. The union representative and principal needed to be aware that her views were not conducive to those students or any student. The administration, accompanied by union representation, addressed the teacher verbally, and the situation was brushed under the rug. I don’t think the impact of the incident translated to those facilitating the conversation. They themselves could not relate and had not dealt with any situations that were similar before, so the impact of the conversation on the teacher was minimal. I realized that I was powerless with my administration and my power was in the classroom where I could integrate the critical conversations with my students. The more we did, the more students of color shared their experiences of being marginalized in the school context, an opportunity to teach students self-advocacy.

Eventually, I joined the school and district leadership committees because I felt that the principal and union representative’s actions were not enough. What about the students I did not teach? Did they just have to navigate these situations on their own? In my capacity on these committees, I did my best to interject the conversations with every opportunity I was given; however, it was clear the committee members were not ready for these conversations. Eventually, it became too heavy for me to carry on my own, so I decided to move on, and my heart ached with that decision. I felt like I was abandoning my students. I still try to reach out to support the district and support their growth in this area. Unfortunately, they still are not ready.

It’s not “only a joke”

Denise Fawcett Facey was a classroom teacher for more than two decades and now writes on education issues. Among her books, Can I Be in Your Class offers tips and techniques for whole-child education that makes learning more engaging and relevant:

A racist joke, the racist undertones of a comment, prejudiced behavior, an outright racist diatribe—regardless of whether it’s supposedly done in a lighthearted manner or with overt malice, teachers who observe racism have to call it out. Racism does not persist merely because it’s supported by its adherents. It also continues because those who oppose it remain silent. When teachers take an unequivocal stand against it, we ultimately protect our students, who are invariably the biggest victims of racist teachers.

When it’s a supposed joke, for example, take a vocal stand against it. Remaining silent or laughing just to get along condones the behavior, which basically ensures that it will be repeated. Firmly stating that you find no humor in racism, and then walking away, likely prevents a recurrence. And athough some might say, “It’s only a joke,” the mindset from which such “jokes” spring is decidedly racist. Refusing to tolerate it compels the offender to consider—perhaps for the first time—the appropriateness of what is said.

Even when racists feign ignorance, observers can’t do the same. Whether it’s the insidiousness of stereotyping or the long-lasting harm of blatant exclusion, racist colleagues may pretend not to realize what they’re doing. However, those who hear or see these racist behaviors have to correct the inaccuracies and reverse the exclusions.

It is the racist teacher who makes negative comments about students’ names. It is the racist teacher who ensures that students of color are excluded from gifted classes. It is the racist teacher who pressures the Asian student to excel in math or science and assumes the Latinx student cannot. It is the racist teacher who disciplines boys of color more harshly than all others. And it is all other teachers who have the obligation to negate these efforts, to address the offense directly, to ensure that students are protected.

Teachers of color are often more observant of words and behaviors with racist overtones as each can recount myriad instances of both seeing and experiencing colleagues’ racism. And while white teachers cognizant of the pervasiveness of racism are aware of having seen and heard it as well, those divergent experiences are distinguished by the extent to which one is personally impacted. That often determines our reactions as well, but it shouldn’t. All teachers have a responsibility to respond in resolute opposition to a colleague’s racism in any form. Our students’ well-being depends on it.

“We have to speak up”

Felicia Darling, Ph.D., is an instructor, author, researcher, and teacher educator. She wrote the book, and research articles including Currently, Felicia teaches math at the Santa Rosa Junior College in California:

Many of us who are not persons of color, who do not personally experience discrimination on a daily basis, have this tendency to think that racism occurs out there, away from us, in the media. We have this erroneous idea that racist acts are these dramatic or violent behaviors that are captured on video and posted on Instagram. However, racism is ubiquitous. It happens every day through small, almost invisible acts, in our classrooms, in our parent-teacher conferences, in our tenure-review meetings, and in our faculty meetings.

Also, racism does not just happen. We do it. In any given day, white colleagues interrupt colleagues of color during meetings; leaders take up the ideas of faculty of color less frequently than those of white faculty sitting at the table; teachers have lower expectations for students of color; students disproportionally use words like “aggressive” more frequently on teacher evaluations of Black women; and Black students are suspended more frequently than white students for the exact same behaviors.

We are the agents of racism. Therefore, the responsibility for disrupting systems of inequity falls directly on our shoulders. When a colleague says or does something racist, we have to speak up. While the specific thing we say or do does matter, what is most important is that we say or do something. If we do nothing, we are complicit in the racist act.

We cannot place the burden of speaking up onto people of color, either, given their precarious position in the existing power structure. White people are uniquely positioned to exert significant influence to disrupt the existing inequitable systems, and they must speak up. Here are some things that are better than doing nothing when encountering racist comments or acts among your colleagues. They are listed somewhat in order of increasing potency: Be loudly silent by frowning and glaring; tell the offending teacher privately that their speech or behavior is not OK and why; give the teacher anti-racist readings; publicly express your dismay about the comment or behavior in the moment or later; ask an administrator to provide a schoolwide training, submit a written complaint to your supervisor for repeated or egregious offenses; privately communicate empathy to those who might have been slighted by the remarks or acts; procure funding for a community of practice around equity to transform campus discourse and behavior; and solicit funding for ongoing equity education. Responding in more than one of the above ways is even more powerful.

The important thing to remember is that if we do nothing when someone acts in a racist manner, we are complicit in the act. Stopping racism is the responsibility of each and every one of us.

Thanks to Sawsan, Denise, and Felicia for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via or And if you missed any of the highlights from the first eight years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. The list doesn’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

I am also creating a