Although virtual schools continue to grow each year, more research and accountability are needed to foster and support effective full-time online educational environments, says a report from the National School Boards Association.

“We want to harness all the benefits of technology to really propel student learning, ... but at the same time, we find the lack of really good information about results and accountability really troubling,” said Patte Barth, a co-author of the report and the director of the NSBA’s Center for Public Education, which provides data and research for school board members and other educators. She spoke in a conference call tied to the release of the report this month.

Full-time online schools have gained 50,000 more students in the past year alone, bringing the total number of students taking part in such virtual learning environments up to 250,000, according to the , “Searching for the Reality of Virtual 69��ý.”

However, research on how successful those schools are is mixed, it says, with a majority of it finding higher dropout rates and lower test scores for full-time online students than for their counterparts in brick-and-mortar schools.

On the other hand, two small-scale studies found that online students actually had higher rates of academic growth, suggesting that online learning can be an effective way of educating students, according to the report from the NSBA.

Taking Attendance

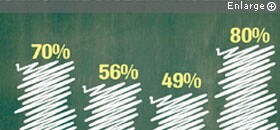

One reason behind the low completion rates could be the way that online schools monitor student participation and progress, says the report. While almost all schools look to final grades as a way to track student progress, only about half of districts with students in online courses track their time spent online or their log-in activity.

Key Recommendations

• School leaders must demand more information about virtual-learning options before using them in their schools and districts. The wide variety of formats and providers of online education, as well as the mixed research about its results, requires the attention of education leaders before heading down this path.

• Research regarding the success of virtual schools is mixed. While the majority of research and reporting has found lower achievement and higher dropout rates in virtual vs. traditional schools, a handful of studies have found higher academic achievement in online-learning environments, suggesting it could be an effective way of delivering education. As a result, districts need to think carefully about how best to track students in virtual education environments and what key elements lead to success in online learning.

• Funding for virtual schools should be based on the actual cost of educating students in an online environment. More research is needed to determine that number and track how taxpayer dollars are being spent.

SOURCE: National School Boards Association

“It’s hard to imagine a classroom where they don’t take attendance every day,” Ms. Barth said.

John Watson, the founder of the Durango, Colo.-based Evergreen Education Group, which publishes the annual , noted that the need for more and better research is often a concern in K-12 education.

“It’s valuable to note ... that state data systems, for the most part, are not up to the task of providing good information that tracks individual student growth, student mobility, and other data elements that are more relevant to online students than the overall student population,” Mr. Watson said.

Susan D. Patrick, the president and chief executive officer of the Vienna, Va.-based International Association for K-12 Online Learning, or iNACOL, agreed.

“The NSBA should recognize that most traditional schools are not collecting the data in detail for student persistence and productivity, and a much more thorough collection and reporting of data for students across the board—in every learning environment—is appreciated,” she said.

The report distinguishes between reporting for virtual schools and traditional schools, which Ms. Patrick said should be clarified.

“All charter schools are required to follow the same reporting and accountability requirements as required by the state, without exception to virtual schools,” she said. “The authors are describing the same pitfalls with lack of data in traditional schools and applying them to virtual programs without context, including true funding, process, medium, delivery, obstacles, legislation, policy, and quality-assurance benchmarks.”

Even if virtual schools and traditional schools are held to the same standards, one of the studies of virtual schools cited by the report showed that a virtual school run by a for-profit company only had 27 percent of its students meet AYP under the No Child Left Behind law, Ms. Barth said.

“They are held accountable on that indicator, but [the results] aren’t very hopeful,” she said. And more information is needed to determine which school is responsible for students’ progress if they are taking half of their classes online and the other half in a traditional setting, Ms. Barth said.

“That’s really one of the issues that we saw that needs to be sorted out,” she said.

The report gathered data from a number of other prominent reports and research about online learning in K-12, including the U.S. Department of Education’s meta-analysis of research on online education and the annual “Keeping Pace with K-12 Online Learning” report.

Funding Problems

The NSBA report also looks at how virtual schools receive funding, which varies from state to state. In some cases, it says, the funding follows the student from his or her district; in others, the student receives funding based on the district where the virtual school operates.

Either way, the report argues, the funding model is not actually based on how much it costs to educate the student in a virtual learning model.

“The absence of accounting for the true cost of virtual education leads to a lack of accountability for many virtual schools,” it says.

Keeping track of how many students are in virtual education, and where the funding for those students is going, is difficult, the report says, citing Colorado as an example.

In that state, schools receive per-pupil aid based on where each student is on Oct. 1 of each year. The NSBA report says studies have found, however, that 30 percent to 50 percent of students in virtual charter schools in Colorado leave those schools after that date, transferring the cost of their education to their home schools while the virtual schools keep the funding.

In response to concerns about online schools, the report offers three recommendations for school board members, policymakers, and educators, when considering virtual education as an option.

Despite the words of caution about online learning, Ms. Barth said that the NSBA’s Center for Public Education is a supporter of such education.

“We are very much in favor of it,” she said. “It will happen, and it needs to happen. ... What we’re trying to do as a center is to send out a note of caution that because something is working in one high school somewhere doesn’t mean you can rapidly expand it and expect the same results, and you certainly can’t expand it without data-collection systems in place.”