National attention centered last week on a Florida school resource officer’s arrest of two young students, including a 6-year-old girl who reportedly kicked another student while having a temper tantrum.

The incident occurred at a charter school, the Lucious & Emma Nixon Academy, in Orlando. Officer Dennis Turner, who reportedly had previously been disciplined for excessive use of force, was fired days later after outrage poured in from around the country, and the local prosecutor dropped the charges against the students.

The Orange County school district maintains its own school police force, but Turner appears to have been a city police officer hired as a SRO, possibly to meet the mandates of a new Florida school safety law. That law requires schools to have an armed staff member in every school as a way to prevent mass shootings or minimize the harm caused by an armed assailant, and districts throughout the state have scrambled to meet its requirements. Charter schools aren’t exempt. In 2018, the city of Orlando and the county agreed to hire a SRO that the city’s 13 charters would share, according to television station WFTV.

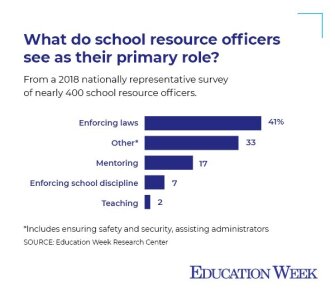

Nationwide, more schools are hiring school resource officers: 45 percent of schools report having a SRO, and there are more than 52,000 of them in U.S. schools, according to U.S. Department of Education data. Fear of shootings in schools is a major driver of the rise in police in K-12 settings, but few SROs will ever encounter a shooter in their school building.

Although research on SROs’ impact is still thin, many civil rights groups argue that police in schools criminalize the behavior of students of color and push them into a “school to prison” pipeline, and the Orlando incident embodies many of their concerns.

Regardless of the merits of police presence in schools, districts can and should take steps to minimize similar incidents—and be clear about SROs’ roles. Here’s how.

Some Best Practices

There are emerging best practices for districts and schools employing school resource officers on how to set clear expectations for their duties and behavior.

Know who you are hiring. Many SROs are “on loan” from their city or county police department. (Some larger districts have their own police forces.) It’s not clear how many SROs are subjected to additional background checks before they are assigned to schools, but at the very least, a history of discipline issues or other warning signs in an officer’s personnel file ought to preclude that officer from being assigned to work with children.

Train your SROs. Training is no guarantee that something won’t go wrong, but it is an opportunity to expose SROs to some of the unique challenges and opportunities of the role. That can include how students with behavioral disabilities react, how to serve as a mentor or guide, and the disparities that black students face in terms of discipline and suspension rates at schools. National groups like the National Association of School Resource Officers offer 40-hour SRO training, and some states require similar minimum training hours.

Be specific on the content of the training. According to the Education Commission of the States, 29 states currently specify some topics that must be covered in SRO training. But the requirements are vague or defer to other state bodies to determine their content.

Maryland’s policy is among the most specific. Among other things, officers have to know about de-escalation tactics, disability awareness, and implicit bias, with attention to racial and ethnic disparities. (A recent Education Week Research Center survey found that most SROs said they’d had experience with de-escalation techniques, but far fewer had training on how to work with special education students, recognize childhood trauma, or understand adolescent brain development.)

Write a specific MOU outlining the SRO’s duties. A memorandum of understanding should spell out exactly what SROs are responsible for and where their authority stops. This provides clarity, and, in a worst-case scenario, it is also part of the district’s legal liability—a document courts can rely on to determine whether an SRO’s behavior was appropriate or not.

One of the most important pieces of the MOU is whether an SRO can be called upon to enforce the school or district’s discipline policies. Many experts argue that SROs should handle only criminal activity at school, while dealing with infractions of the disciplinary code should be administrators’ responsibility.

Some MOUs go even further: New York City’s new MOU, for example, explicitly says that SROs should avoid criminal procedures for most misdemeanors and should only arrest students at school for violent offenses or felonies.

Consider accountability tools. In an eye-opening finding, a recent federal school safety data release revealed that the percentage of schools reporting the use of police body cameras increased from 16 percent in 2015-16 to 33 percent in 2017-18.

The evidence on use of bodycams in general is mixed—they don’t help much if officers don’t turn them on—but they are theoretically one of the few ways districts can get a sense of the nature of student and police interactions in school.