Includes updates and/or revisions.

American schools have made modest progress in closing the achievement gap between black and white students in math and reading, though that narrowing varies by grade and subject and from state to state, a shows.

The academic disparity generally seen between African-American and white students is one of the most enduring challenges in American education. Policymakers at the state and particularly the federal level have crafted laws aimed at lifting student performance among minority and disadvantaged populations.

The study, issued by the National Center for Education Statistics, suggests that the results of those efforts are mixed.

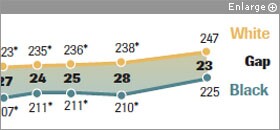

In mathematics, the achievement gap between the two groups has narrowed significantly among 9- and 13-year-olds since 1978, though it has remained statistically unchanged since 1999, according to the study.

Black students are slowly closing the achievement gap with white students based on scores on the National Assessment of Education Progress.

* Statistically different from 2004.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics

In reading, the gap was statistically unchanged among 9-year-olds, but it has narrowed at age 13 since 1980. Since 1999, the gap has narrowed statistically among students in both age groups.

The study, which focused solely on white and black students’ performance, is based on an analysis of several years of results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Federal officials regularly release NAEP results on differences in the achievement of black and white students. The new report, however, examines achievement gaps more deeply by showing how disparities in test performance have changed over time, not only at the national level but also among individual states.

The National Center for Education Statistics, which administers NAEP, is the main statistical arm of the U.S. Department of Education. The study should yield “better hypotheses” about the disparity between white and black students’ performance, and help education leaders “ask themselves some tough policy questions,” acting NCES Commissioner Stuart Kerachsky told reporters after the report’s release.

Federal officials are planning to release a separate report on the achievement gap between Hispanic and white students next year, said Peggy Carr, the associate nces commissioner for assessment.

Some States Close Gap

NAEP results have received special scrutiny in the years since the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act. That measure received bipartisan congressional support and was signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2002. One of its central goals was to bring greater attention to the low performance of minority and disadvantaged students. The new study shows achievement gaps in some categories, such as 4th grade math, remaining statistically unchanged since 2003, while narrowing significantly in other categories. such as 4th grade reading.

The results are based on two different sets of reading and math NAEP results: test scores among 4th and 8th graders for the states and the nation, known as the “main NAEP” and reported from the early 1990s; and long-term-trend results for 9- and 13-year-olds, results of which care reported from the late 1970s. Because the main NAEP assesses only public schools for state exams, NCES officials say, the study reports solely on public schools.

Among 4th graders, both black and white students have made significant gains in reading and math since the early 1990s, and the gap between those groups has narrowed, the study found. Yet at the 8th grade level, while the reading and math scores of African-American and white students also rose, the gaps did not close by a statistically relevant margin. U.S. Rep. George Miller, D-Calif., the chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee, saw progress in some areas but was troubled by some of the persistent disparities between minority and white students.

“The fact that there has been no significant closing of the achievement gap in reading for 8th grade students is alarming,” Mr. Miller said in a statement. “Research shows us that students who struggle in middle school are much more likely to drop out of high school.”

U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan linked the racial disparities to many minorities students’ well-documented lack of access to high-quality teaching. He called on states and districts to use federal stimulus money to “increase the pace of school reform efforts.”

“When schools serving children of color are primarily staffed by less experienced, less effective teachers, the effects are tragic,” Mr. Duncan said in a statement. “The children most in need of great teaching to accelerate their learning are not being served adequately, and in many cases, they are being denied their civil right to an education that prepares them to graduate high school prepared for college and careers.”

The study also reports on the achievement gaps in individual states, though not every jurisdiction was included because some did not have sufficient numbers of white or black students. State results in closing the racial performance gap were mixed.

Fourteen states plus the District of Columbia narrowed the math achievement gap between 1992 and 2007 in 4th grade, but only four states—Arkansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, and Texas—reduced the disparity between 1990 and 2007 in 8th grade.

In reading, three states—Delaware, Florida, and New Jersey—narrowed the achievement gap between black and white 4th graders between 1992 and 2007, but at the 8th grade level, no states did that from the 1990s to 2007, the study found.

The differences in state peformance were in some cases striking. Delaware had an achievement gap that was significantly smaller than the national average in three of the four math and reading achievement categories. Wisconsin and Nebraska, by contrast, showed some of the largest disparities between white and black students in various grade levels and subjects. Wisconsin’s achievement gap was significantly larger than the national average in all four categories for math and reading.

“It’s certainly something we’ve known we need to work on, and it’s not going to change overnight,” said Patrick Gasper, a spokesman for Wisconsin’s education department.

Wisconsin officials hope to lessen the disparity through several steps, including implementing a corrective action plan in the Milwaukee schools, where low performance is probably “driving a lot of the [NAEP] numbers,” Mr. Gasper said. That plan includes standardizing the reading curriculum, expanding before- and after-school tutoring, and extending instructional time in reading and math, he said.

Other efforts are being undertaken statewide in areas such as early-childhood education “to stop the achievement gap” before it starts, Mr. Gasper said.

Kati Haycock, the president of the Education Trust, a Washington advocacy organization focused on closing academic disparities across racial and income groups, said the NCES study showed states and the nation making progress, though the slow pace of change “makes you worry.”

“It’s very clear that states that have rock-bottom low standards—that doesn’t pay off,” Ms. Haycock said. States that have directly addressed their academic shortcomings have made greater strides, she argued.

While she was grateful for the NCES study, Ms. Haycock was less certain if the report itself would spark changes in states, which she said tend to ignore federal data they don’t like.

“NAEP results by themselves don’t get a lot of traction in the states,” Ms. Haycock said. “Is this helpful? Yes. It will bring more attention. But less than we wish.”