When President Bush spoke about the No Child Left Behind Act in the Rose Garden of the White House this week, he added two words to his typical description of the law’s central goal: “or above.”

“Every child must learn to read and do math at, or above, grade level,” after meeting with civil rights leaders who support the reauthorization of the nearly 6-year-old law.

The addition of those two words acknowledges that Mr. Bush and other policymakers are considering a variety of changes to the NCLB law to encourage schools to go beyond the teaching of basic skills. The president’s comments also came the day before the release of a poll suggesting that the American public believes schools aren’t teaching critical thinking and other skills needed in the workforce.

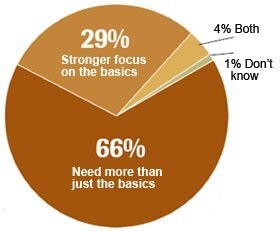

(requires Microsoft PowerPoint) found that two-thirds believe schools should teach “more than just the basics” and schools are failing to adequately teach skills they consider important, such as writing, creativity, and teamwork. The survey has a margin of error of plus or minus 3.5 percentage points.

“Are all the kids getting the skills they need?” said Ken Kay, the president of the Partnership for 21st Century Skills, which sponsored the poll. The Tucson, Ariz.-based group works with six states to craft policies that prepare students for the workforce.

“It’s appropriate to raise those questions in the context of the reauthorization of No Child Left Behind,” Mr. Kay said.

Looking for Solutions

So far, House leaders have proposed a variety of changes to the NCLB law that would expand its scope beyond basic skills in reading and mathematics.

The law’s critics say the accountability system’s focus on getting students to proficiency in those two subjects has encouraged schools to overemphasize reading and math skills, often at low levels.

A survey of registered voters found that two-thirds of respondents say the nation’s schools need to go beyond the basics of reading, writing, and mathematics.

SOURCE: Partnership for 21st Century Skills

Under released by House education leaders late this summer, the reauthorized law would initiate the development of new tests and curricula that supporters say would broaden the types of skills taught and assessed. The draft also would change the accountability system to determine the success of schools and districts by analyzing the academic growth of individual students, which would encourage schools to maintain their focus on students after they have reached proficiency.

Leaders of the House Education and Labor Committee have been meeting since early September to craft a bipartisan bill based on the drafts, with the hopes that the House would approve legislation by the end of the year.

But Republicans said last week that they were disappointed in the progress of those talks. “We have been clear from the outset that Republican support was contingent on maintaining the core principles of the law,” Alexa Marrero, a spokeswoman for committee Republicans, said late last week. “Despite our best efforts, the draft bill does not meet that test. We remain hopeful that the bill can be improved to produce a strong NCLB reauthorization we can support.”

Tom Kiley, a spokesman for Rep. George Miller, D-Calif., the chairman of the House education committee, said Rep. Miller remains committed to working with Republicans to reach consensus on the future of the NCLB law.

Democrats and Republicans disagree about some of the measures that Rep. Miller has proposed to try to shift the emphasis of the types of skills schools should teach.

For example, the House draft would allow 15 states to give districts the power to build an accountability system around their own testing programs. Such freedom, supporters of the experiment say, would allow districts to analyze portfolios of students’ work and conduct other assessments that measure students’ progress on skills that go beyond the basics.

“If they are done right, it would provide the opportunity to assess higher-order thinking across subjects,” said Monty Neill, the co-executive director of the Center for Fair & Open Testing. The Cambridge, Mass.-based nonprofit group, also known as FairTest, is a critic of standardized tests and the reliance on them to measure student progress.

But there’s no guarantee that districts would be able to establish tests that are rigorous and comparable to their states’ standards, critics of the proposal say.

“You run the risk of having different tests for different kids and destroying the equity component” of the current law, said Amy Wilkins, the vice president of government affairs and communications at the Education Trust, a Washington-based research and advocacy group that is one of the current law’s strongest supporters.

The Education Trust supports other provisions in the draft, Ms. Wilkins added. A proposal to finance districts’ efforts to write new curricula tied to their states’ standards is a “step in the right direction,” she said. But she would prefer that states lead such undertakings, not districts, as the draft proposes.

Her organization also is the leading proponent of encouraging states to rewrite their standards so that they measure students’ readiness to enter college and the workplace. (“Law’s Timeline on Proficiency Under Debate,” Sept. 26, 2007.)

Making School Challenging

Although leading policymakers don’t agree on how to increase the rigor of academic expectations under the law, they do appear to agree that it needs to happen.

“We believe in setting high standards, and we believe that by setting high standards, we encourage greater results for every child,” President Bush said after his Oct. 9 meeting with the members of the civil rights community. “And now the question is whether or not we will finish the job to ensure that every American child receives a high education—high-quality education.”

In a Sept. 5 speech in which he touted the House NCLB draft’s proposals to enrich the curriculum, Rep. Miller said: “What we are being told now is that the set of skills that people are looking for are far different in the workplace of today.”

“We are told constantly that young people will have to come with a set of skills that will allow them to work together in a collaborative way, finding solutions to problems across companies, across communities, across continents,” the congressman said in the speech to a group of business leaders in Washington. (“House Plan Embraces Subjects Viewed as Neglected,” Sept. 12, 2007.)

The public appears to agree with those sentiments, according to the poll by the Partnership for 21st Century Skills.

For example, 80 percent of those surveyed said teaching students to think critically and to solve problems is extremely important. But just 18 percent believe schools are doing a very good job of that. Respondents also gave low ratings when asked to judge schools’ success in teaching writing, creativity, and collaboration—other skills the public considers important for economic competitiveness.

“I’m struck by how low these numbers are,” said Bill McInturff, a partner in Public Opinion Strategies. The Alexandria, Va.-based Republican polling firm conducted the survey along with Peter D. Hart Research Associates, a Washington firm that works with Democrats.

“People are very, very clearly saying the world we live in is very different,” Mr. McInturff said, “and our schools aren’t doing well enough.”