Fifty years ago this month, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Elementary and Secondary Education Act outside the former one-room schoolhouse in rural Texas he’d once attended. The new law dramatically ramped up Washington’s investment in K-12 education, carving out a role for the federal government in educating the nation’s poorest children.

But shortly after that cinematic ceremony, administrators in the U.S. Office of Education—the predecessor of today’s separate, Cabinet-level department—found themselves with a difficult task.

They needed to write—and enforce—regulations that would ensure states and districts sent the federal dollars to communities with the highest concentrations of poverty and used the money appropriately. And while state and local governments were happy to cash the federal checks, many weren’t nearly as receptive to federal direction.

Five decades and more than half a dozen revisions of the ESEA later, calibrating the proper federal K-12 role remains an elusive goal.

“It’s a tough nut to crack,” said Michael W. Kirst, who in 1965 served in the federal Office of Education—part of what was then the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare—and helped craft and carry out regulations for the new law.

“This is a nation of states and a nation of local control. ... It’s the nature of our federalism that makes this job so hard,” he said.

Mr. Kirst, who today is the president of the California state school board, now finds himself on the other side of the federal-state equation, pushing back against the Education Department on the current version of the law he once helped implement. His state has had run-ins with U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan on issues ranging from teacher evaluation and accountability to state data systems.

Given his past experience in Washington, Mr. Kirst sympathizes with Mr. Duncan. “He’s facing many of the very same issues we did” in the 1960s, Mr. Kirst said.

Consensus Unraveled

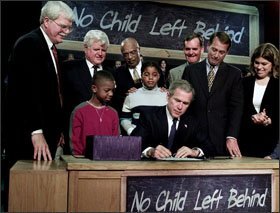

After hitting a high-water mark with bipartisan passage in late 2001 of the No Child Left Behind Act—an ESEA overhaul that gave the U.S. Department of Education unprecedented sway over how states measured student achievement and intervened in failing schools—the seeming consensus among policymakers around a strong federal role in holding schools accountable for student performance has unraveled.

It’s clear from the current tone of the debate and bills introduced in Congress that the next version of the ESEA will give states a lot more control over key parts of the law, including accountability, teacher quality, and spending.

But lawmakers and the White House have been at an impasse for nearly a decade on just how far to go in shrinking the federal footprint without jeopardizing the ESEA’s focus on providing an equitable education to the poorest children.

That conflict has its roots in the original legislation, which was born with an identity crisis of sorts. The 1965 law sought to target new federal funding—more than $1 billion in the first year, with few strings attached—to areas with high concentrations of poor students. But the law itself was somewhat vague when it came to targeting disadvantaged children, in part to build the necessary support in Congress to pass it quickly.

“There was no strategy around how all this was going to work with respect to a process for improving education,” said Christopher T. Cross, a former assistant secretary in President George H.W. Bush’s administration who also served as a top aide to Republicans on the House education committee in the 1970s. “It was just, ‘These are poor districts, they need the money. Trust people to do the right thing.’ It’s come back to haunt everybody now,” said Mr. Cross, now the chairman of the Bethesda-based consulting group Cross & Joftus.

Lingering Echoes

The original ESEA rocketed through Congress in less than 100 days—a turnaround time that today sounds astonishing, considering that lawmakers have been grappling for more than eight years with writing a successor to the NCLB version of the law.

But, as it turns out, much of the rhetoric against federal involvement in K-12 education during congressional consideration of the ESEA in 1965 don’t sound much different from discussions about rewriting the law in 2015.

In the 1960s, conservative Republicans and Southern Democrats—some representing states that were struggling with or resisting desegregation—argued that the ESEA and its attached aid would give the federal government a reason to interfere with local control of schools.

In late March of 1965, Rep. Frank T. Bow, R-Ohio, said the Johnson administration and supporters of the bill “are eager to promote what they call the excellence of educational opportunity, and they can do so only by imposing their views about curriculum, teaching methods, and textbooks on the local school districts. … This bill is the foot in the door for federal control of education, make no mistake about it.”

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, D-N.Y., made the case for a stronger federal role. And since the federal government was about to pour additional money into schools, he wanted language requiring a careful assessment of whether Title I actually improved student outcomes.

“We really ought to have some evaluation in there, and some measurement as to whether any good is happening,” he said, according to Mr. Cross’ 2004 book, Political Education: National Policy Comes of Age.

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act is divided into 10 “titles,” covering a wide range of federal education policy and funding issues. Here’s a look at those parts of the current version of the law, the No Child Left Behind Act.

Title I

Improving the Academic Achievement of the Disadvantaged—The heart of the law, which sets out rules for formula grants to help districts educate disadvantaged students. Title I includes provisions related to accountability, annual testing, school improvement, and content standards.

Title II

Preparing, Training, and Recruiting High-Quality Teachers and Principals—Governs formula grants to states for improving educator quality. The money can be used for such purposes as teacher recruitment and retention and class-size reduction.

Title III

Language Instruction for Limited-English-Proficient and Immigrant 69��ý—Allocates formula grants to states to help English-language learners succeed academically and learn English.

Title IV

21st Century 69��ý—Governs programs in a range of areas that include violence prevention, school climate, and after-school initiatives.

Title V

Promoting Informed Parental Choice and Innovative Programs—Authorizes aid for innovative programs, charter schools, magnet schools, and other such efforts.

Title VI

Flexibility and Accountability—Allocates grants to states to develop assessments and programs for rural schools, among other things.

Title VII

Indian, Native Hawaiian, and Alaska Native Education—Authorizes grants for Indian, Native Hawaiian, and Alaska Native education.

Title VIII

Impact Aid Program—Deals with funding to districts that have a major federal presence, such as an Indian reservation or a military base.

Title IX

General Provisions—Though it shares a name with another federal education law barring discrimination on the basis of sex in programs receiving federal funds, Title IX of the ESEA includes important provisions of its own. Among them are sections governing “maintenance of effort”; equal access to school facilities; the U.S. secretary of education’s waiver authority; and prohibitions on federally sponsored testing, collection of personally identifiable student data, and distribution of contraceptives in schools.

Title X

Repeals, Redesignations, and Amendments to Other Statutes—Authorizes the McKinney-Vento homeless student program, among other provisions.

SOURCE: U.S. Congress

Sen. Kennedy’s ideas were largely kept from consideration in order to secure swift passage of the legislation. Instead, Congress added some vague provisions around evaluation. But nearly 40 years later, similar views were championed by his younger brother, Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, D-Mass., when he was helping to write the NCLB law with President George W. Bush.

Secretary Duncan continues to see a place for the federal government in ensuring that students get access to an equitable and high-quality education.

“It’s an education law, but it’s a civil rights law. That is at the heart of what this thing is,” Mr. Duncan said in an interview last week.

Early Enforcement

Sending billions of dollars in new federal money out the door with good intentions—but without clear directions—meant the money wasn’t always spent on improving student learning, however. Districts built swimming pools, installed toilets, and purchased audiovisual equipment that sat around collecting dust with money that President Johnson had hoped would equalize opportunity for the poorest children, according to Mr. Cross’ book.

And some districts were accused by advocates of taking federal aid and then failing to give minority students the same opportunities as those of white students, an obvious affront to the goals of desegregation.

For instance, in Benton County, Miss., Title I dollars were used at a “white high school” for a summer math and English program, according to a 1969 report on the program—titled “Is It Helping Poor Children?: Title I of ESEA"—by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Washington Research Project. But at an all-black school, the money paid for a homemaking course for girls.

“We suspect these black girls are being trained with Title I money to become maids for the local population,” the report’s authors said.

Even as Congress was writing the law, researchers were hard at work on “Equality of Educational Opportunity"—better known as the Coleman Report—named after its lead author, James S. Coleman, a Johns Hopkins University sociologist, which was released the year after the bill passed. It showed that black children started school behind their white peers academically and never really caught up.

The Coleman report “supported the notion that the money should be protected in its route to poor kids,” said Edmund W. Gordon, a professor emeritus of psychology at Yale University and Teachers College, Columbia University, and a longtime scholar on racial achievement gaps. He was on the advisory committee that assisted in designing the Coleman study.

Congress, over the course of more than half a dozen rewrites of the ESEA, eventually tightened the reins.

Lawmakers required, for instance, that Title I money be seen as an extra, not a replacement, for state and local aid. And they called for Title I schools to get an amount of state and local money comparable to schools with more privileged populations—a goal the nation is still grappling with.

“It does seem as though the funding disparities are an aspect of equality of opportunity that really hasn’t [been] addressed,” said Elizabeth H. DeBray, a professor of education administration and policy at the University of Georgia College of Education in Athens.

“The federal role has evolved into something that’s very focused on adequate yearly progress and outcome equity,” she said. “There could be a commensurate focus on those things that make a difference with respect to opportunity to learn.”

Civil Rights Focus

Over the years, the law, primarily aimed—at least rhetorically—at combating poverty, has taken on more of a civil rights flavor. The NCLB law, for example, requires states to intervene in schools that aren’t getting good results with minority students, even if the student population as a whole is succeeding.

Discrimination and inequality in schools may have decreased a lot since the mid-1960s, but those problems still persist, said Elizabeth King, the director of education policy at The Leadership Conference for Civil and Human Rights, a coalition in Washington.

“It looks different now. Maybe [students are] not being trained to be domestics, but ... when schools dumb down assignments, when they ask less of children than they are capable of, ... [students] aren’t getting everything they need to exercise the rights that they are entitled to,” Ms. King said.

Meanwhile, the idea of sending out federal money to schools has become less controversial as Title I aid has merged into the bloodstream of school district finances. These days, the money blankets the nation’s congressional districts—meaning it wouldn’t be easy to scrap the law entirely.

The original ESEA passed with only marginal GOP help in the House. But, by the time the law was updated in 1978, it received broad bipartisan support, according to Presidents, Congress, and the Public 69��ý: The Politics of Education Reform, by Jack Jennings, who served as an aide to Democrats on the House education committee from 1967 to 1994.

Standards Partnership

Still, objections to the federal role in influencing K-12 policy have dogged the law since initial passage.

Both President Ronald Reagan and, later, GOP Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich made dismantling the federal Education Department—established more than a decade after the ESEA’s passage—a talking point for conservatives. But Democrats and moderate Republicans stood in the way of doing so.

Still, under President Reagan, the federal footprint in the ESEA was rolled back for the first time. A number of programs were combined into a single block grant.

Then came A Nation at Risk, the landmark 1983 report that warned that the nation was slipping dangerously behind its international competitors in preparing students.

The report spurred a flurry of state activity, ultimately giving rise to the standards-based education-redesign movement.

In 1989, the federal government sought to become a partner in those efforts. President George H.W. Bush called a national education summit in Charlottesville, Va., which culminated in a promise to set national education goals and hold the country accountable, somehow, for meeting them.

That set the stage for the federal-state collaboration on standards and accountability that eventually led to the changes embodied the NCLB law and initiatives such as the Common Core State Standards.

The summit was a turning point in the ESEA’s trajectory, said Chester E. Finn Jr., who served in the Education Department under President Reagan. “You could almost break the 50 years” since the passage of the ESEA into two 25-year periods, he said: “Pre- and post-Charlottesville.”

But No Child Left Behind—passed overwhelmingly in the burst of bipartisanship that followed the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks—may have gone too far in ratcheting up the federal role, even for many of those who initially supported the law.

The ESEA law has some desirable features, especially its focus on outcomes for poor and minority children, said Richard A. Carranza, the superintendent of the 57,000-student San Francisco school district, but it also has major downsides.

“You have to continuously fight against the stream. And the stream under NCLB is to teach to the test,” said Mr. Carranza, one of a handful of big-city superintendents who recently met with President Barack Obama to discuss what needs to change about the law. “If you don’t do well on the test, you get a label assigned to your school that you’re a failing school; ... that [narrows] the curriculum.”

Overdue for Rewrite

The NCLB law was never intended to go 13 years without an update—it’s been on the books without revision longer than any previous version of the ESEA. But a polarized Congress has been unable to renew the legislation, despite numerous attempts dating back to 2007.

Most recently, a revision that would significantly scale back the federal role in school turnarounds, teacher quality, standards, and accountability systems is on hold, having failed to gain sufficient support from a contingent of Republicans in the House because it wasn’t conservative enough, in their view.

Meanwhile, Secretary Duncan has issued a series of waivers easing many of the mandates at the heart of the law, requiring states to embrace the Obama administration’s education redesign priorities, including rigorous standards and teacher evaluations tied in part to student outcomes. Mr. Duncan has described the waivers as a new way forward when it comes to a state-federal partnership.

But not everyone sees it that way. The Common Core State Standards have come under siege in a number of states in part because Mr. Duncan encouraged states to adopt them in order to get waivers of certain NCLB provisions.

And the back-and-forth negotiations over the finer points of the accountability plans created under the waivers haven’t gone well, either. For example, Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., the chairman of the Senate education committee, has accused Secretary Duncan of playing a game of “Mother May I?” with states, in which they have to beg for every bit of federal leeway to advance their own goals.

It’s the right time for the federal government to take a step back, Mr. Finn said. In the years since the passage of the NCLB law—much less the original ESEA—states and districts have become much more thoughtful and sophisticated when it comes to educational improvement, he said. If the federal government takes a lighter approach to accountability, “it’s not like we’re cutting the engine on the boat and therefore it’s going dead in the water,” he said.

But Margaret Spellings, who served as education secretary under President George W. Bush and was an architect of the NCLB law while working as a top White House aide, doesn’t buy that argument.

“Locals often like to have the cover of ‘the federal devil made me do it,’ ” Ms. Spellings said. Left to their own devices, states are more likely to succumb to public pressure, she added. But the way policy is going, she said, “we may test [Mr. Finn’s] theory.”

Next Steps: Unclear

Meanwhile, others say a lack of focus on factors beyond school, such as resource inequality, meant that the ESEA would always have limited reach when it comes to really improving student outcomes.

“I think [the ESEA] didn’t really do as much as it could have, or as much as was needed to be done, to improve the education of the people we initially targeted,” said Mr. Gordon, whose experience during the Johnson administration included being tasked to conduct an early evaluation of the federal Head Start preschool program. “I would vote for [the law today], but I wouldn’t vote for it with the same confidence I had in ’65 that it would solve all our problems.”

Pedro Noguera, a professor of education at New York University, says the testing and accountability focus has forced something of a detour from the original purpose of the law. “We’ve moved away from the goal [of equity],” he said, “when we should have been going deeper and further.”

How should the next iteration of the ESEA tackle the political puzzle of the right federal role in K-12? Policymakers may not find an answer anytime soon.

Although congressional lawmakers are eager to rewrite the current law, some doubt whether a highly partisan Congress can advance a major initiative on education, or anything else. Meanwhile, the Obama administration has less than two years remaining, and it’s unclear if the next administration—Democratic or Republican—will continue with the waivers or come up with its own twist on the ESEA.

“What’s happening now is that mistaken policy is being cleaned up,” Mr. Jennings said. “People will want to throw everything out.” The problem, he said, is that “we’re going to throw out the good with the bad. We need another vision.”