Five years after the became law, there’s still a dearth of research evidence to show whether one of the federal measure’s least-tested innovations—a provision that calls for underperforming schools to provide after-school tutoring—has an impact on student achievement.

While an estimated 500,000 students nationwide are expected to receive free tutoring under the law this coming school year, most studies of its or SES, provision track how states and districts are implementing the requirement. Experts estimate that only three states—Georgia, New Mexico, and Tennessee—and districts in four cities—Chicago, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, and Pittsburgh—have looked to see if the services are boosting students’ scores on state tests.

And those studies, for the most part, suggest a mixed picture of success. While most parents report satisfaction with the services, the studies find, the added hours of tutoring have so far produced only small or negligible gains on state reading and mathematics tests.

“There’s a huge amount of money going out to this program with no understanding of whether it will work,” said Gail L. Sunderman, a senior researcher for the who has been studying the program, which has been estimated to cost up to $2.6 billion in 2005.

Criticism Questioned

Industry proponents and other researchers, however, suggest such criticism may be premature. Under the NCLB law, schools that receive money under the for disadvantaged students don’t have to provide supplemental education services until after they have missed student-performance targets three years in a row. That means many SES efforts are still young.

Is it fair, defenders of the provision also ask, to hold after-school programs to the same progress yardsticks that schools have to meet under the federal law?

“It’s extremely challenging to evaluate supplemental education services, given that they take up only 30 or 40 hours of a child’s time throughout the year,” said Steven M. Ross, the director of the at the University of Memphis, which is conducting statewide evaluations of SES programs in nine states, including the just-completed Tennessee study.

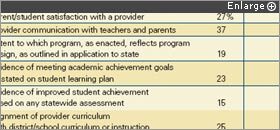

States and districts collect various kinds of data to monitor providers.

SOURCE: Government Accountability Office

High rates of student absenteeism and spotty implementation also confound evaluation efforts. A , the congressional watchdog agency, suggests the program is reaching only a fifth of the low-income students who may be eligible for the free tutoring services.

Most observers agree, though, that the lack of research surrounding the after-school tutoring is ironic given the No Child Left Behind law’s heavy emphasis on “scientifically based research,” a phrase it uses more than 110 times. In addressing supplemental education services, though, the law’s language shifts and calls for programs simply to be “research-based.”

“There’s a difference between research-based and research-proven,” said Marc Dean Millot, the editor of New Education Economy, an Alexandria, Va.-based online newsletter on what he calls the “school improvement industry.”

It wasn’t that no studies had suggested that supplemental instruction, in and of itself, would be a good idea. At least one research review indicates, for instance, that one-on-one tutoring can produce an average gain of two letter grades in a class. But the state and district evaluations produced so far suggest that the student-to-teacher ratios for most SES programs are larger than that.

With or without the research, lawmakers and advocates reasoned that the SES program could be a lifeline for students trapped in failing schools. They also saw extra help after school as better than pulling students out of class, which was the practice under earlier versions of the Title I program. The law also broke new ground by authorizing services from outside providers, from religious organizations to commercial firms.

Evaluation Tools Lacking

The NCLB law puts responsibility for monitoring the supplemental programs on state education departments, but it does not specify how they should go about it. So most states rely on parent-satisfaction surveys, provider reports, attendance figures, and financial records to keep tabs on vendors, according to the GAO survey, conducted in 2005-06.

Only 14 of 50 states factored state test scores into the mix that year, the GAO found, and only six tracked students’ grades or promotion rates. Likewise, few states had the resources to visit programs to see their instructional practices.

States are also charged under the law with compiling lists of state-approved providers from which parents can choose services. Surveys show, though, that states rely heavily on providers’ own reports of success, many of which come from Web sites or annual reports, in making those decisions.

The problem with that practice, according to Patricia Burch, an assistant professor of educational policy studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison , is that providers, who have a financial interest in putting a positive spin on the numbers, are typically vague about how they calculate their effectiveness data .

“It’s hard to know how rigorous these things are because there is so little transparency,” she said. States can remove providers from their lists for failing to produce academic gains, but most experts say few—if any—states have dropped vendors for that reason.

Rigorously evaluating program effectiveness is difficult for states because the federal program provides no added money to do a job that can be highly complex. In the GAO survey, for example, 85 percent of the state administrators said they needed advice from the federal government on methods for evaluating the SES programs in their states.

“We don’t have the capacity to look at effectiveness,” Rachelle Greller, who helps monitor the program for the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, told participants at a national research conference in April. “We can link to student test scores, but the ‘doses’ differ. There are different programs, and student-teacher ratios vary.”

What states need, said Michael J. Thompson, an executive assistant to Wisconsin’s state superintendent, are tests tailored to the academic content that students are getting in their after-school programs. “And that doesn’t exist right now,” he added.

Steve Pines, the executive director of the , a Rockville, Md.-based trade group that represents private SES providers, agrees that state tests may be “too blunt an instrument” to yield dramatic learning gains. “Our members are not shy about being held accountable to high standards,” he said, but evaluations need to take into account a wide range of outcomes to paint a fair picture.

Mr. Millot said providers need to be more active about making their case to districts and identifying “best practices” for the kinds of services they provide. “Maybe what we need,” he added, “is a federal research-and-development program for the whole industry,”

Smattering of Studies

A range of researchers, advocates, and policymakers are calling on the federal government to underwrite a national study of the SES program’s effectiveness.

This summer, scholars from the Santa Monica, Calif.-based plan to release a federally funded study looking at the SES and school choice provisions in nine large urban districts. In the meantime, districts are using various methods to assess SES. Among the recent reports:

• Mr. Ross’ research group, looking at state-test data for six Tennessee districts, (Microsoft Word required). For 2005-06, though, students tutored by two of the providers made fewer academic gains than did a demographically matched group of nontutored students. Citing the small size of student samples, the analysts made no judgments about the other two dozen-plus providers in those districts. Their report was released in March.

• In the 2005-06 school year, Chicago’s SES program produced “small but significant” improvements in reading for 3rd through 8th graders and “negligible” gains for the same grades in math, . The evaluation also found the district’s own tutoring program, called A.I.M. High, the most cost-effective.

• In Los Angeles, on state language arts and math tests than students who applied for the program but never attended . The effects were concentrated among elementary students. 69��ý with the highest attendance rates also made the greatest gains. Released in February, the report drew on achievement data for 2005-06.

Some experts say gains would be stronger if providers worked in tandem with their students’ teachers. In several studies, teachers cited a lack of communication with outside tutors. In Tennessee, many teachers were not even aware their students were receiving the services, according to Mr. Ross. “I think that’s the biggest issue,” he said. “I don’t think SES will work very well unless it’s connected to the classroom.”