Includes updates and/or revisions.

New federal statistics shared late last month about thousands of schools and districts show that students across the country don’t have equal access to a rigorous education, experienced teachers, early education, and school counselors.

Using amassed from about 72,000 schools in the 7,000 American districts each with more than 3,000 students, the U.S. Department of Education’s office of civil rights sought a picture of how equitable—or inequitable—schools are within a district and across states.

“These data are incredible and revelatory,” said Russlynn Ali, the department’s assistant secretary for civil rights. “They paint a portrait of a sad truth in American schools: Fundamental fairness hasn’t reached whole groups of students.”

In a call with reporters, Ms. Ali said the data are a powerful source of information and one step toward resolving the gaps in achievement among students of different backgrounds and abilities.

“For a long time, we have fallen short on why the achievement gap exists,” she said, but added the data collected show “gaps in opportunity, in access to courses and other resources that continue to hobble students across the country.”

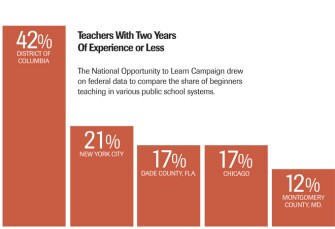

The National Opportunity to Learn Campaign drew on federal data to compare the share of beginners teaching in various public school systems.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education

She said she hopes the data, which offer information about more than three-quarters of the nation’s students and a little less than half of all districts, will spur action by parents, advocates, and policymakers, although will not be taking any specific action with the data right now.

“Transparency is the path to reform,” she said. The data from the 2009-10 school year “shine a light on where the opportunity gaps exist so that we can really make headway on closing the achievement gap.”

Examples Cited

While the data available online are on individual schools and districts, and are not aggregated by state, the department’s own crunching of the numbers offered a glimpse of the extent of some educational inequities at the national level. Among the findings:

• Some 3,000 schools serving about 500,000 high school students weren’t offering Algebra 2 classes that school year, and more than 2 million students in 7,300 schools were not offered calculus.

• At schools where the majority of students were African-American, teachers were twice as likely to have only one or two years of experience compared with schools within the same district that had a majority-white student body.

• Less than one-fourth of school districts reported that they ran prekindergarten programs for children from poor families;

• Girls were underrepresented in physics, while boys were underrepresented in Algebra 2;

• Just 2 percent of the students with disabilities were taking at least one Advanced Placement class; and

• While students learning English comprised 6 percent of the total high school population, they accounted for 15 percent of the students for whom algebra was the highest-level math course taken by the end of high school.

“These data show that far too many students are still not getting access to the kinds of classes, resources and opportunities they need to be successful,” U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said in a statement.

New Information

Demographic data similar to those offered last month have been collected since 1968, but this is the most ambitious to date, adding about 10,000 schools more than the last collection in 2006. In addition to enrollment figures and racial information about students, the office asked how many AP courses high schools offer, how many students with disabilities are enrolled in those classes, and whether a particular school is a magnet, charter, or alternative school, or a school for special education students only.

For the first time, districts were asked to report about students’ participation in algebra, college-preparatory courses such as AP classes, and teacher experience. The results varied widely, even within districts.

For example, within Boston public schools, Charlestown High School, a magnet school with about 910 students, offered nine AP courses in 2009-10. At Fenway High, also a Boston magnet school but with only about 300 students, there were none that year. Fenway had three full-time guidance counselor positions, while on the other hand, Charlestown had 2.8.

At Robert F. Kennedy High School in New York City, which has 720 students, high school students could choose from among seven AP classes, but at Abraham Lincoln High, also in New York City, where there were 2,520 students, there were just two AP courses.

In Washington, D.C., and the surrounding areas, teacher experience varied dramatically from district to district. In the school districts around the District of Columbia system, the statistics show that an average of about one in 10 teachers had two years of experience or less. Within the District of Columbia, it was an average of two out of every five teachers, although those ratios vary from school to school.

In another example of unequal opportunities, Miami Beach High School in South Florida, there were four physics classes and three calculus classes. Across the Miami-Dade school district, Miami Edison High offered no physics and a single section of calculus.

Offering a full sequence of math and science courses, not just ap classes, is critical, Ms. Ali said, especially with President Obama’s goal of leading the world in college graduates by 2020.

“As important as the opportunity gap is, parents and community members don’t have access to actionable data about opportunity gaps,” said Daria Hall, director of K-12 policy for the Education Trust, a Washington-based research and advocacy group. “Today’s release is an important first step toward remedying that. The hope, absolutely, is that individuals and activists will see data and take action and these data will drive bigger conversations at the district level, the state level, the federal level.”

She also hopes the data will spur school administrators to take action and ask themselves questions about what policies may be contributing to the inequities that may exist in their schools and districts.

One federal lawmaker quickly chimed in to say the data further fuel the argument for rewriting the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the current version of which is known as the No Child Left Behind law.

“If we’re serious about closing the achievement gap and bringing our schools to the future, then our education reform efforts have to be serious, comprehensive and deliberate as well,” said U.S. Rep. George Miller, D-Calif., who is the senior Democrat on the House Education and the Workforce Committee, in a statement. “Many schools aren’t educationally where they need to be, which ultimately means many students won’t graduate ready to succeed in a career or in higher education. This new information reiterates that the federal government’s role in ensuring an equal education for all students is just as critical as ever.”

Student-Rights Bill

U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah, D-Pa., has proposed two pieces of legislation that could address some of the issues raised by the data.

One is the Student Bill of Rights, which would require states to provide ideal or adequate access to highly effective teachers, early childhood education, a college preparatory curricula, and equitable instructional resources. States would define what is ideal or adequate, and they would have to create plans to remediate any areas in which they are deficient.

He also wants to close a loophole in the current ESEA that would restore one of the purposes of the law, which was to provide supplemental funding to districts and schools to cover some of the added costs of educating low-income students. For example, his ESEA Fiscal Fairness Act would require accounting of real dollars spent per student in schools, including differences in salary due to teachers’ years of experience.

Kim Hymes, director of policy and advocacy at the Council for Exceptional Children, an Arlington, Va., group that represents students with disabilities, welcomed the data, but said it renewed concerns about the small percentage of students with disabilities enrolled in AP courses.

“If you really look at what is the largest percentage of students with disabilities, it’s speech disorders. Most students with disabilities do not have a cognitive disability,” she said, and therefore should not be discounted as unable to tackle AP courses. “There are many misconceptions that exist about students who ... are designated as having a disability.”

The department also gathered information about how many students a school doesn’t promote from one grade to the next, rates of teacher absenteeism, school funding, the use of restraints and seclusion with students with disabilities, and other information about student discipline. That information will be released later this year. The next time the information is solicited from schools—the surveys are typically done every two years—Ms. Ali said it will include every public school in the country.