Includes updates and/or revisions.

In a preschool class at Gardner Academy, a public elementary school near downtown San Jose, teacher Rosemary Zavala sketched a tree as she fired off questions about what plants need to grow. “¿Qué necesitan las plantas?” she asked her 4-year-old charges in Spanish.

“Las flores toman agua” was the exuberant answer from one girl, who said that flowers drink water. A boy answered in English: “I saw a tree in my yard.”

The next day, Ms. Zavala’s questions about plants would continue—but in English.

This classroom, with its steady stream of lively, vocabulary-laden conversations in Spanish and in English, is what many educators and advocates hope represents the future of language instruction in the United States for both English-language learners and native English-speakers.

The numbers of dual-language-immersion programs like this one have been steadily growing in public schools over the past decade or so, rising to more than 2,000 in 2011-12, according to estimates from national experts.

That growth has come even as the numbers of transitional-bilingual-education programs shrank in the aftermath of heated, politically charged ballot initiatives pushing English immersion in states like Arizona, Massachusetts, and here in California.

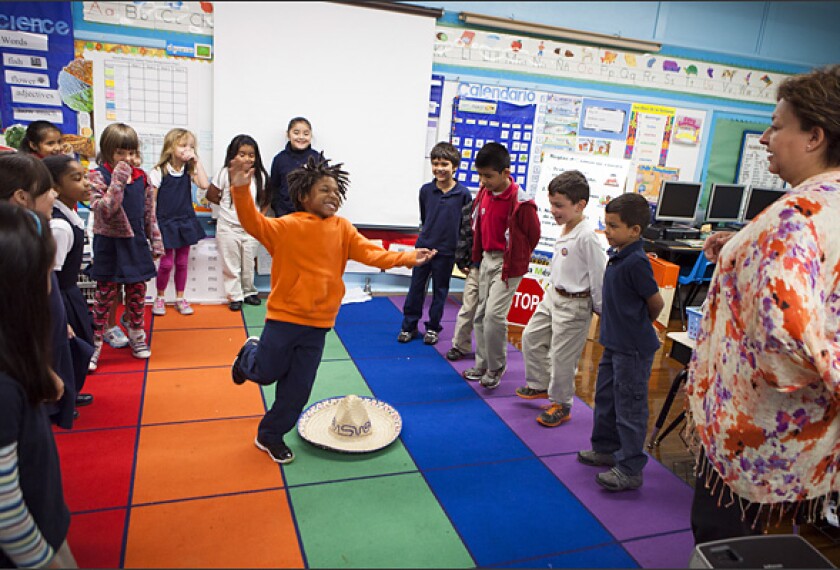

Learning in English and Spanish

69��ý at Gardner Academy in San Jose, Calif., and now increasingly nationwide, are taught in two languages.

Experts say the interest in dual-language programs now is driven by an increased demand for bilingual and biliterate workers and by educators who see positive impacts on academic achievement for both English-learners and students already fluent in English.

In California—home to more than 1 million ELL students and some of the fiercest battles over bilingual education—the earlier controversies are showing signs of ebbing.

While the state’s Proposition 227 ballot initiative, approved by voters in 1998, pushed districts to replace many bilingual education programs with English-immersion for English-learners, the state is now taking steps to encourage bilingualism for all students: Graduating seniors can earn a “seal of biliteracy” on their high school transcripts and diplomas, which signifies they have reached fluency in English and a second language. Last year, 6,000 graduates in the state earned the seal.

“The momentum behind these programs is really amazing,” said Virginia P. Collier, a professor emeritus of education at George Mason University, in Virginia, who has studied dual-language programs extensively.

“And we are not talking about a remedial, separate program for English-learners or foreign-language programs just for students with picky parents,” she said. “These are now mainstream programs where we’re seeing a lot of integration of native speakers of the second language with students who are native English-speakers.”

‘An Asset’

Part of the 33,000-student San Jose Unified School District, Gardner Academy offers a two-way immersion program, in which native speakers of English and native speakers of Spanish learn both languages in the same classroom. Generally, to be considered a two-way program, at least one-third of the students must be native speakers of the second language.

Many of Ms. Zavala’s 4-year-olds will continue to receive at least half their instruction in Spanish as they move into kindergarten, 1st grade, and beyond. The goal is to establish strong literacy skills in English and Spanish in the early grades, and to produce fully bilingual, biliterate students by the end of elementary school. Because of the state’s Proposition 227 law, parents must “opt” for their children to enroll in the two-way program.

In one-way immersion, another form of dual-language learning, either native English-speakers or native speakers of the second language make up all or most of the students enrolled and instruction takes place in two languages.

The number of one-way and two-way programs is roughly equal, according to Leonides Gómez, an education professor at the University of Texas-Pan American in Edinburg, Texas, who developed a two-way-immersion model that is widely used in the state’s public schools.

There are variations in how dual-language programs work, but all of them share a few hallmark features.

At least half the instructional time is spent in the second language, although in the early grades, it may take up as much as 90 percent. There must also be distinct separation of the two languages, unlike in transitional bilingual education, in which teachers and students alike mix their use of both languages.

Spanish is by far the most prevalent second language taught in dual programs, followed by Mandarin Chinese and French, according to national language experts.

For English-language learners, the dual-immersion experience is dramatically different from that in most other bilingual education programs, in which teachers use the native language to help teach English with the goal of moving students into regular classes as quickly as possible, said Mr. Gómez, who serves on the board of the National Association for Bilingual Education, or NABE.

“The goal isn’t to run away from one language or another, but to really educate the child in both and to use the native language as a resource and an asset,” said Mr. Gómez. “Content is content, and skills are skills. When you learn both in two or more languages, it moves you to a different level of comprehension, capacity, and brain elasticity.”

Role of Motivation

Research examining the effects of dual-language programs has shown some promising results for years, although there is not consensus that it’s the best method for teaching English-language learners. One problem with discerning the effect of dual-language methods is determining how much self-selection is a factor. All such programs are programs of choice, with students and their families having the motivation to opt for the dual-language route.

Another factor is the great variability among dual-language programs.

“I think many of the new programs aren’t able to achieve the ideal conditions for them to truly work, especially for English-learners,” said Don Soifer, the executive vice president of the Lexington Institute, a think tank in Arlington, Va., that generally supports English immersion for the teaching of English-learners.

For starters, Mr. Soifer said, finding teachers is a major challenge because they need strong skills in two languages, as well as subject-matter competence. He said it’s also necessary for two-way programs to have an even balance of native English-speakers, a feature that he says is difficult to achieve in some districts.

Still, several studies in recent years have demonstrated that ELL students and other frequently low-performing groups, such as African-American students, do well in dual-language programs.

Ms. Collier and her research partner, Wayne P. Thomas, found in a 2002 study that ELLs in dual-language programs were able to close the achievement gap with their native English-speaking peers, and that the programs achieved important intangible goals, such as increased parental involvement. The study examined 20 years of data on ELLs in 15 states who were enrolled in dual-language, transitional-bilingual-education, and English-only programs.

Ms. Collier and Mr. Thomas are also conducting an ongoing study of students in two-way dual-language programs, most of them in Spanish and English, in North Carolina. The researchers have found so far that gaps in reading and math achievement between English-learners enrolled in dual-language classes and their white peers who are native English-speakers are smaller than gaps between ELLs who are not in such classes and white students.

The data are also showing that English-speaking African-American students who are in dual-language programs are outscoring black peers who are in non-dual classrooms, Ms. Collier said.

Leading the Nation

Texas has more dual-language immersion programs than any other state—with between 700 and 800 of them in schools—including some of the most mature, according to several experts.

One district in the state’s Rio Grande Valley along the Mexican border—the Pharr-San Juan-Alamo Independent School District—is likely to become the nation’s first to have dual-language programs in all its schools, including middle and high school, Mr. Gómez said. In June, the fourth cohort of students who have been in dual language since kindergarten will graduate from the district’s four high schools.

In Utah, a statewide dual-language-immersion initiative funded through the legislature—the first such broad-scale effort in the United States, according to experts—is now in its third year, said Gregg Roberts, a specialist in world languages and dual-language immersion for the state office of education.

By next fall, public elementary schools across Utah will offer 80 programs under the state initiative, with roughly 15,000 students enrolled in Spanish, Mandarin, French, and Portuguese. The goal is to have 30,000 students enrolled in 100 programs by 2014, Mr. Roberts said.

“Utah is a small state and, for our future economic development and the national security of our country, we have to educate students who are multilingual,” he said. “There is broad agreement in our state about that. It’s not a red or a blue issue here.”

Many of Utah’s programs so far are two-way Spanish-English immersion, drawing on the state’s growing Latino immigrant community, said Myriam Met, an expert on immersion programs who is working closely with Utah officials on the initiative.

But the most in-demand programs in Utah are Mandarin. Ms. Met said there were fewer than 10 Chinese immersion programs in the nation in 2000. The current estimate stands at 75 Chinese programs, and by next fall, roughly a quarter of those will be in Utah, she said.

Some of the nation’s oldest Chinese programs are offered in the 56,000-student San Francisco public schools.

Most students start in one of the city’s five elementary schools, where they split instructional time between English and Cantonese or English and Mandarin. Eventually, many end up at Abraham Lincoln High School, where a mix of native Chinese-speakers and students who have been in the immersion program since the early grades take advanced Chinese-language courses, in addition to at least two content-area courses each year in Cantonese.

Amber Sevilla, a 14-year-old freshman in the Chinese-immersion program at Lincoln, is fluent in English, Cantonese, and Mandarin. She has been in Chinese immersion since kindergarten and learned some Chinese at home from her grandmother. Through middle school, nearly all her instruction was conducted in Chinese, including math. Currently, she is taking health education and college and career education in Chinese.

“I’m excited that I can count on being bilingual and biliterate as I go to college, and I know it’s going to be an advantage for me even though I don’t know yet what I want to do for my career,” said Ms. Sevilla. “It’s hard work, but it’s worth it.”

Like nearly all her classmates in the immersion program, Ms. Sevilla is on track to earn California’s new state seal of biliteracy.

Cognitive Benefits

Rosa Molina, the executive director of Two-Way CABE, an advocacy group for dual-language programs that is an affiliate of the California Association for Bilingual Education, said students like Ms. Sevilla benefit in multiple ways.

“They preserve their primary language or their heritage language, they develop a broader worldview that they take into college and the work world, and they gain huge advantages in their cognitive development that translates into flexibility in their thinking and the ability to successfully tackle really rigorous coursework,” Ms. Molina said.

Advocates for English-learners emphasize the importance of expanding programs that are truly two-way and fully accessible to ELLs. Laurie Olsen, a national expert on English-learners who designed the instructional model in use at the Gardner Academy in San Jose, cautions against allowing programs to become dominated by middle- and upper-income students whose parents want them to learn a second language. If that happens, she said, one of the most promising approaches to closing the achievement gap between English-learners and fluent English-speakers will be squandered.

“We know that English-learners who develop proficiency in their home language do better in English and in accessing academic content,” she said. “Yet we still live in a world where the belief is wide that English should be enough.”