Corrected: The original version of this story misstated the location of the headquarters for the advocacy organization Stand for Children. It is based in Portland, Ore., and has an affiliate in Chicago.

As the majority of legislative sessions around the country come to a close, many states will finish the season having pushed through policy changes that are likely to have a notable impact on teachers.

Building on the momentum from the previous two years, in which lawmakers began aggressively pursuing teacher-related reforms, about a dozen states passed laws since January that curb or otherwise modify teacher tenure, teacher evaluations, last-in-first-out policies, and collective bargaining. And several more states are on the verge of passing similar laws as they wrap up their legislative sessions.

Jennifer Dounay Zinth, a senior policy analyst at the Denver-based , which has been tracking the legislation closely, said the protracted interest in revamping the teaching profession amounts to a “sea change.”

“It’s hard to get your arms around—not just the number of bills being enacted but the breadth and depth of changes being made,” she said. “If somebody had asked me in 2010 if I thought states would be doing away with teacher tenure or the Wisconsin union battle [would have happened], I wouldn’t have listed either as something I expected down the pipeline” in 2011.

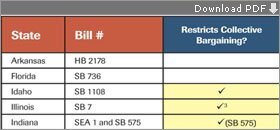

In the first six months of this year, at least a dozen state legislatures passed laws, which their governors signed, altering teachers’ conditions of employment. Actions affected collective bargaining, seniority, evaluations, and tenure, among other policies. In some categories without checkmarks, similar legislation by that state may have taken effect in previous years. And some states’ actions on tenure, seniority, and evaluation could ultimately have an influence on collective bargaining.

SOURCES: Education Commission of the States; National Conference of State Legislatures; Education Week

During this session, Florida, Nevada, Ohio, and Utah ended the practice of automatically laying off the newest teachers when reductions in force are necessary (so-called last-in-first-out policies). And Ms. Zinth noted that there have been 11 policy changes so far this year that affect union operations, including new restrictions on collective bargaining in seven states.

Idaho made some of the most sweeping changes to teacher-related policies, limiting collective bargaining to compensation and benefits, phasing out tenure, tying teacher evaluations to student-achievement data, and ending the last-in-first-out policy. Sandi Jacobs, the vice president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, a Washington-based research and advocacy group, said the fact that the policy changes were enacted wasn’t “particularly surprising” because Idaho’s education commissioner, Tom Luna, had made his intention to tackle teacher issues clear for some time. “But I think the sheer volume is a surprise,” she added.

Snowball Effect

Legislators began eyeing teacher quality for a variety of reasons. Many experts agree that a primary motivator was a 2009 report by the New York City-based New Teacher Project, which trains teachers, that highlighted schools’ failure to distinguish between effective and ineffective teachers.

There have also been “consistent indicators showing that student-achievement levels put our global competitiveness at risk,” Ms. Jacobs pointed out. Results from the 2009 Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA, indicated that the United States scored statistically lower than 17 other member nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in math.

In addition, December 2009 marked the beginning of the Race to the Top competition, which offered states points for incorporating student-achievement data into teacher evaluations.

According to Michelle Exstrom, an education program principal at the National Conference of State Legislatures, Race to the Top “certainly put the carrot out there” for legislators to make systemic changes to the teaching profession.

But now, despite the fact that the first round of Race to the Top money is no longer on the table, this second wave of states has kept up—or even bolstered—the teaching reform agenda.

According to Ms. Jacobs, teacher quality was an issue a lot of states had been afraid take on, so “once the ball was rolling in some states, it continued rolling.” The first group of states to pass legislation “opened the door to show other states that this is not an immovable subject,” she said.

On the other hand, Ed Muir, the deputy director of the research and information-services department at the American Federation of Teachers, contended that, for the most part, the new legislation has been driven by budget cuts. The vast majority of states are facing continued budget shortfalls in the coming fiscal year.

“They’re trying to dress up disinvestment in the guise of shining reform,” Mr. Muir said.

He criticized recent legislation that gives teachers “less input and voice into how their work is structured and less [job] security” as “very wrong-headed.”

Collaboration, Contention

Recent lawmaking was most publicly divisive in Wisconsin, where Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican, signed legislation stripping teachers and many other public workers of their collective bargaining rights, sparking massive protests across the state.

But Ms. Exstrom of the NCSL maintains that states like Wisconsin that began their reform efforts with a stab at collective bargaining may have a harder time passing teacher-related policies down the road.

“In some states, there’s enough political will on one side to make those changes and get legislation through,” she said, “but in other states where cooperation is needed from the unions, it’s not going to happen.”

Mr. Muir agreed. “If you want to have collaboration and cooperation, the way to do it is to sit at the bargaining table,” he said. “If you’re taking away people’s rights, you can’t then go back and say, ‘We didn’t get cooperation.’ That’s dishonest and ridiculous.”

In Illinois, lawmakers took a less contentious approach, engaging in closed-door negotiations with advocacy groups and the unions. The resulting bill ultimately passed both chambers with ease.

Mr. Muir called that a “better” course of action than what occurred in most states. “We had to make some sacrifices, but overall the process was much more collaborative,” he said.

The Illinois law differs from other recent legislation in several ways. It puts more specific limitations on collective bargaining, including—in a section that pertains only to Chicago—requiring at least 75 percent of the union’s members to agree to a work stoppage for it to occur. And while most states’ new laws toughen tenure statutes, the Illinois law actually accelerates the tenure process for teachers who receive the highest marks. The Illinois legislation also makes it easier to dismiss ineffective tenured teachers.

Jonah Edelman, the chief executive officer of Stand for Children, a Portland-based advocacy organization that supported the Illinois legislation, said that is a substantial change. “This is paradigmatically fundamental stuff in terms of who is teaching children in Illinois,” he said. “It’s a misunderstanding when people assume that because it was a collaborative process, that equates to diluted policy.”

Evaluation Trumps

Illinois was part of both the first and second waves of states to pass teaching reforms, having enacted a law in 2010 that incorporates student achievement into teacher evaluations. According to the NCTQ’s Ms. Jacobs, “The evaluation piece is the real linchpin in any performance-management system.” All other teacher-related reform, in areas such as tenure, licensure, professional development, and compensation, are dependent on being able to “consistently and clearly identify who’s effective and who’s not,” she said.

Eight states in this legislative session alone linked evaluations to student achievement, with most eventually requiring that 50 percent of an evaluation score be based on student data.

Ms. Exstrom of the NCSL said the 50 percent benchmark was a direct result of Race to the Top, but that other states still considering such changes are “not sure that makes sense. That’s just a percentage put out there by the [U.S.] Department of Ed., and everybody followed suit.”

While only a handful of state governments are still in session, the legislative momentum on these issues is ongoing. At press time, both Texas and Michigan were awaiting their governors’ signatures on teacher-related measures. Both states’ legislatures passed bills that would replace last-in-first-out policies with performance-based layoffs. A series of four bills in Michigan would give schools more flexibility in dismissing teachers and link student achievement to evaluations. Michigan state Sen. Phil Pavlov, who chairs the education committee, said in an interview that his state looked to Florida and to Colorado, which passed the influential Senate Bill 191 last year, as models for their reform legislation.

Stakeholders agree that the weight of the new laws rides on forthcoming regulations. “These are very complex systems a lot of states are putting in place,” said Ms. Jacobs. While this second wave of states will benefit from looking to the systems of the early adopters, there is still “lots of training that has to accompany this and lots of new territory with questions that have to be answered,” she said.

“It’s a really heavy lift. If not done well, jobs are at stake, student success is at stake. Sustainability is tied to the quality of what gets implemented.”

Assistant Editor Sean Cavanagh contributed to this report.