�Ԩ���.”

By Monday, the students were told, they’d have to spend at least two hours reading the books they’d selected. That wasn’t a problem for Julius, who, at 13, had developed a love for prose. But his anticipated journey into the land of wizards and witches would have to wait until he and his classmates took a real-life journey.

“We have a few moments left, so I want you to think back to the 4th grade, before Amistad,” said Luke Harrison, a boyish-looking 29-year-old in his third year teaching at the school. Along with colleagues, he’d organized a visit to nearby Yale University that afternoon. “How many of you thought about going to college then?”

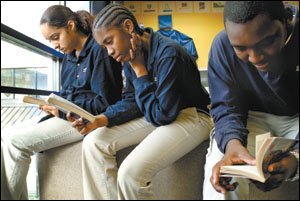

Only two of Harrison’s 16 students—all wearing the school uniform of navy blue polo shirt and tan khakis—raised their hands. The New Haven district cites its overall graduation rate as 75 percent, but among minorities the rates are lower—53 percent for African Americans and just 41 percent for Hispanics, according to a recent study done by the Urban Institute’s Education Policy Center. And according to district figures, the average combined math and verbal SAT score for New Haven students is 826, hundreds of points below the minimum required for top colleges.

“And today?” Harrison continued.

This time, 14 youngsters indicated postsecondary aspirations.

“I didn’t even know what college was,” Julius said as he adjusted his black wire-rimmed glasses. Many of his classmates nodded in solidarity.

“Why are you planning to go now?” Harrison asked.

“I want to show my mom how much I appreciate her,” LaDietra Cohen answered, her brown eyes flashing with enthusiasm. “She grew up on the streets, and I don’t want to go there.”

“I know, um, if I don’t go, I’ll be, um, miserable,” Julius added, displaying the occasional verbal tic that’s the only vestige of the awkwardness he felt when he entered Amistad in 5th grade. “Because I’ll have to work 10 jobs to keep myself from going hungry and, um, other stuff that messes people up.”

Julius—like many of his classmates—knows of what he speaks. His father is currently serving a 10-year sentence for robbery in a New York state prison. He was incarcerated for an earlier offense not long after Julius was born, and he won’t be eligible for parole until his son is a junior in high school. The two have never met.

Although Julius is now on track to get into college, that wasn’t always the case. His struggles in elementary school led his mother to seek counseling for him and, eventually, enrollment at Amistad, which was founded in 1999 by a group of Yale Law School students seeking to close the achievement gap between Connecticut’s mostly white suburban and mostly minority urban students.

It’s a bit early to tell whether Amistad, which combines a stringent curriculum with individualized attention, will play a significant role in populating colleges—its first 6th grade class is due to graduate from high school this spring. But back in mid-November, 25 of that class’s 32 students wereon track, with 24 of them applying for college admission, according to school officials. And with 75 to 85 percent of its once-remedial students now mastering the various subjects on Connecticut’s standardized tests (30 percent higher than the state average), Amistad has proved it can close the gap.

Just how the school has been able to do that is perhaps best exemplified by Julius, who three years ago showed little interest in any kind of education at all.

Early in his school career, Julius seemed destined to become a dropout or worse, according to his mother, 33-year-old Santia Bennett. He attended a public elementary school not far from Amistad while the family, including his now 5-year-old half-sister, Jewels, lived in a neighborhood Bennett characterized as drug- and crime-ridden.

“Julius was very badly served at that school,” she recalled. “The work wasn’t challenging and very repetitive. Julius rebelled, saying, ‘We already did this.’ His teacher got in his face, but he wouldn’t comply. Then the office would call.”

Bennett met often with teachers and administrators and agreed to take her son for professional counseling, beginning in 2nd grade, “to prevent him from being pushed into special education,” she explained.

A social worker helping Julius with anger management discovered that he was so depressed, he had thoughts of suicide.Underlying issues included his absent father (whose name Santia Bennett does not want to share publicly), the death of a grandmotherly great-aunt, and Bennett’s breakup with her common-law husband—the only father figure Julius had ever known.

Thanks to therapy, Julius’ in-class outbursts declined somewhat, Bennett said, but his academic performance did not improve. He did so poorly on the 4th grade Connecticut Mastery Tests—which cover math, reading, and writing and are also administered in grades 6 and 8—he almost had to repeat the year.

Bennett, who, between two jobs as a nursing assistant, works six days a week to support her family, could not afford to transfer Julius to a private or parochial school, so she looked into Amistad, which she knew about from letters the school had mailed to area residents. Like any charter, Amistad is a public school funded only partly by its district and the state—$7,625 per student versus $12,640 for other New Haven schools. In return, it operates under its own guidelines.

In many ways, Amistad is like a private school, with a long academic day (7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.) and average-size classes (roughly 22 kids each) taught by state-certified, nonunionized teachers who’ve been aggressively recruited. The curriculum is standards-based, and students are expected to master the skills demanded by the CMTs. But they’re also given highly individualized attention (more on that later).

When the group from Yale, led by Dacia Toll and Stefan Pryor, began their education research in 1998, they were told repeatedly that one reason for the achievement gap is that urban kids are “impossible” to teach. Undaunted, the law students came to consider educating at-risk youngsters “the Number 1 civil rights issue in the nation,” according to Toll. A charter school was the only answer, they reasoned, and they made up for the budget shortfall by enlisting the financial and logistical aid of Connecticut philanthropists and business and political leaders.

Within a few years, the percentage of Amistad students mastering subjects on the CMTs was two to four times higher than students in other New Haven schools. In 2003, that meant 75 percent of Amistad 8th graders had mastered math, 80 percent reading, and 85 percent writing. This is significant, considering that 84 percent of the 270 students qualify for reduced-price or free lunches, and most enter the school two grade levels behind their peers. By law, they’re chosen from a blind lottery; this past year, 600 applicants vied for 70 slots.

If the name Amistad sounds familiar, it’s because the founders took it from a Cuban schooner that was the setting of a famous slave revolt in 1839. After more than 50 Africans, who were being transported to a sugar plantation in the Caribbean, seized the boat and demanded that the crew take them back home, the ship was captured by U.S. officials along the East Coast and docked in Connecticut. The Africans were imprisoned as their case was tried all the way to the Supreme Court, with John Quincy Adams serving as the defense attorney. International slave trading had been banned in the United States by that point, and the slaves were acquitted and sent back to Africa as free men.

But in 2002, Julius knew nothing of the school or its namesake when he entered the cheerful, two-story brick building that had once served as a distribution center for a computer software company. He only knew that Amistad seemed like a strange place.

On his first day, the 5th grader was ushered into the gym, where “morning circle,” the daily pep rally, was under way. As older students pounded on African drums, teachers and kids ringed the basketball court chanting slogans such as “To push ourselves, to learn, to achieve our very best!”

Running the length of one wall was a banner with block letters that read “R-E-A-C-H,” for “respect, enthusiasm, achievement, citizenship, and hard work.” The sign—and others throughout Amistad, including one demanding “NO EXCUSES”—articulated the school’s rubric, according to which students are constantly coached and evaluated.

This auditory and visual barrage was designed with two purposes in mind: to establish Amistad’s mission and to thwart defiant new students. But Julius refused to join the circle that morning. Asked why, he later told one instructor: “I’m angry my mom sent me to a school where teachers lie. Morning circle isn’t really a circle—it’s a rectangle. So that’s what you should call it.”

The next two years weren’t easy. Julius continued his pattern of “completely shutting down,” as one teacher described his behavior. He refused to do class assignments or homework he didn’t enjoy. He went semi-catatonic for hours at a time, mostly during the written tests that Amistad administers every six weeks, tests similar to the CMTs and aimed at assessing student progress. An anxious Julius often refused to participate.

“I’m tired and don’t see the point,” he told Vivien Perez, Amistad’s social worker, after being referred for counseling.

“Typically, the 5th and 6th graders find the transition very traumatic,” explained Roxanna Lopez, Julius’ 5th grade teacher. She cited the extended school day, during which the kids follow a rigorous curriculum that begins with phonics and arithmetic in the early grades and eventually progresses to algebra and Shakespeare.

They also must sign a contract pledging to abide by a strict behavioral code. But there is, as the school’s director, Matthew Taylor, explained, some room for maneuvering. “We want kids to rebel, if they must, in safe ways—for example, not tucking a shirt in completely,” he said.

Teachers at Amistad are, in fact, encouraged to address individual needs. In Julius’ case, Lopez—an energetic, attractive woman in her early 30s—often met with her student after school “to reset his objectives,” she explained. “We don’t lower standards for anyone. Instead, we build a strong relationship to inspire motivation.”

“Miss Perez talked to me a lot about how things we do come from the subconscious,” Julius recalled. “Then I realized that thinking about my father abandoning me made me angry at everybody.”

Meanwhile, math teacher Teron McFadden supplied Julius with pertinent, if sobering, statistics. “I talked to Julius one-on-one and in front of the class when he refused to follow directions, pointing out things like college-age African American males are 10 times more likely to go to prison than white peers,” said McFadden, who is black. “I was trying to get across that his behavior was putting him on track to become a statistic.”

Julius eventually decided, in 7th grade, to stop dwelling on his biological father and dedicate himself to “becoming a better person.” That meant listening to teachers, socializing with classmates—whom he’d avoided since 5th grade—and raising his grades.

Although he’d been tracked in the lowest of Amistad’s three academic groupings in 6th grade, Julius established himself as a consistent A-minus student the following year. When math, in particular, was a concern in 7th grade, he attended an intensive tutorial Amistad offers on Saturday mornings. Julius’ most recent algebra grade was 92, and comments on his report card praise him for becoming “an incredible math student.”

It’s no surprise that he plans to study engineering in college.

Julius’ school day, just prior to Veterans Day weekend, actually began the night before—with homework. On Wednesday, November 9,he arrived in the family’s modest apartment at 6 p.m., as usual. Before dinner, he sat at the kitchen table reading Stargirl, a young adult novel being studied in class, and made notes.

His sister, Jewels, played in the living room as his mother took a momentary breather on the couch. Along with working full time, Santia Bennett has been attending the University of New Haven part time for several years. She plans to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice this year, then follow up with law school on a scholarship that will enable her to provide the same level of care for her children.

While Julius is quiet and intense, Bennett is an outgoing dynamo. Both, however, share a determination to persevere, and discipline has become ingrained. Julius’ access to TV and the computer is severely limited on school nights, and he doesn’t hang out much with friends, partly to focus on studies and partly because of local gang activity. Two years ago, the Bennetts moved to the working-class neighborhood of Newhallville, just two miles from Amistad, to make it easier for Santia’s mother to baby-sit while Bennett works the night shift. Even though Newhallville is safer than the neighborhood they used to live in, last year Julius was mugged on the way to the barbershop, escaping with minor bruises.

Between 9 and 10 p.m., with most of his schoolwork finished, Julius relaxed by reading a Harry Potter chapter and working on his own superhero drawings in Japanese-animation style. He was then off to bed and up the next morning at 5:45 a.m. to make the 45-minute commute to Amistad via school bus.

At the beginning of reading class, Luke Harrison handed out photocopies of “At the Cancer Clinic,” a poem by Ted Kooser, the current U.S. poet laureate and winner of a 2005 Pulitzer Prize.

Kooser’s poem is usually high school material, but Harrison’s class had met and surpassed grade-level literacy requirements. During their first three years at Amistad, students attend two reading classes and one writing class every day, with each period lasting 65 minutes. In 8th grade, one reading class is eliminated in favor of preparations for the college application process they’ll face in high school.

As Harrison’s students took turns reciting lines from Kooser’s work, the teacher interjected, “There’s a word the author repeats, which I want you to find, then jot down ideas about why.”

LaDietra Cohen suggested out loud that the word was “weight,” citing these lines:

Each bends to the weight of an arm... The sick woman peers from under her funny knit cap to watch each foot swing scuffing forward and take its turn under her weight.

“Why did the author, being a poet who pays attention to every word, choose to repeat it?” Harrison asked.

Julius volunteered, “You know how some people say, ‘This is weighing down on me and making me sad’?”

A bit later, Harrison initiated a discussion about the poem’s final lines:

...Grace fills the clean mold of this moment and all the shuffling magazines grow still.

“What does ‘grace’ mean?” Julius inquired.

“I’m glad you asked,” Harrison said. “What do you think?”

“Is it ‘kindness’?” Julius guessed.

“Yes, but coming from somewhere else, like God. It helps people deal better with troubles.”

On the campus of Yale University later that afternoon, Julius’ inquisitiveness surfaced repeatedly. Fifty-two Amistad 8thgraders filed out of the Afro-American Cultural Center after listening to three panels composed mostly of minority Yale students, who talked about developing the work ethic and time-management skills necessary to navigate an Ivy League school.

Julius walked beside his group’s tour guide, Deana Brown, a senior from Brooklyn majoring in political science, as they traversed pathways winding between stately neo-Gothic structures. When Brown pointed out the Yale School of Architecture building as they turned onto York Street, he asked, “What’s a graduate school?”

“After college, it’s where you specialize, usually in something professional,” she explained.

“So that’s how you get a master’s or doctorate degree?”

�Ԩ���.”

Julius would say later, in private, that an advanced degree is exactly what he’d like to earn so that he can “design cars that use less gas and buildings for the homeless, not just things that make us more comfortable.”

But he still has high school to get through. And Santia Bennett worries that without the kind of guidance he’s had at Amistad, her son might be in trouble. So the plan is to have Julius continue at Amistad, which intends to open a high school in New Haven in September. While there, Julius hopes to do well enough on AP and SAT exams to get into a competitive college—perhaps on a scholarship.

The planned Amistad High School is part of an ever-expanding reform effort that, in 2003, led Amistad’s leadership team to form a nonprofit organization called Achievement First. In 2004, it founded a K-8 charter school, also in New Haven, and plans to eventually turn it into a K-12 college-prep institute. Last year, Achievement First opened two new charter schools in Brooklyn, New York, with plans to open two more there in the fall. All of the schools are modeled on Amistad.

Dacia Toll, an Amistad co-founder who is now president of Achievement First, served as Amistad’s first director until the end of Julius’ 7th grade year. She insisted that students, teachers, parents, and administrators together had created the school and were equally responsible for its success. And she cited Julius as a prime example of a student who’s earning “the freedom education bestows,” which includes “career opportunities, the respect with which he’ll be treated, and the greater resources he’ll bring to social problems.”

“Julius resisted so much at first, but he’s transformed into someone with the fire to learn,” Toll added. “It’s become a pleasure to see him in class with his face so alive.”