As an aspiring actress, Monica PĂ©rez had to go to Lincoln High School, the magnet campus for visual and performing arts in the San Jose Unified School District.

| |

| (Requires .) |

She spent her freshman year at another school waiting to get into Lincoln High. When she finally started at the popular school near downtown San Jose at the beginning of 10th grade, she marveled at the array of theater, music, and dance classes she could choose from.

But even more striking, she says, was the heavier academic load at Lincoln High, where classes such as Algebra 2, which were electives at her former high school in a neighboring district, were required. To graduate on time from Lincoln High School in 2007, she must take an extra year each of math, science, and foreign language.

“Here, the work is really challenging, and I’ve had the highest GPA of my life,” Ms. Pérez, now a 16-year-old junior, said during a lunch break at Lincoln High this month. “Here, I feel like I can get into the colleges I really want to.”

Nurturing such ambition and achievement in this district, where 70 percent of the 32,000 students are from racial- or ethnic-minority groups, began eight years ago when the school board abolished what had been a two-tiered high school system. In the top tier, the students who aimed the highest—most of them white and Asian—had nearly exclusive access to college-preparatory and Advanced Placement courses. The second tier was for everyone else—many of them Latino—and offered basic courses and electives that prepared students for little beyond high school.

Responding to demands by parents and a concern that high school was just too easy, the San Jose school board adopted some of the most rigorous graduation requirements in California.

The premise was simple: Increase academic standards and expectations for all students, and they would rise up to meet them. More students would go to college.

And pressure on the district was intense. In 1971, Hispanic parents had sued the district in federal court, alleging segregation. The lawsuit resulted years later in a court-enforced agreement to boost Latino achievement.

Beginning with the incoming freshmen of 1998, San Jose Unified students became the first high school class in the state to be required to complete the University of California’s minimum subject-area requirements for freshman admission—a series of core academic courses and electives commonly called the “A-G sequence.” For students, A-G means at least three years of college-prep math, four years of English, three years of science, 3½ years of social studies, two years of foreign language, and one year of visual or performing arts.

In addition to modeling its graduation requirements after the A-G sequence, the district tacked on a year of visual and performing arts and 40 hours of community service.

The plan was popular with parents and students, but controversial nonetheless.

Skeptics feared that large numbers of overwhelmed students would drop out. Supporters of vocational education worried the college-prep curriculum was too restrictive, especially for students who wanted to go to work after high school. And teachers fretted that the district would not supply the extra time and help that both they and students would need to succeed.

“It was very daunting at the time, especially for the math department,” said Kristine Kimura, a mathematics teacher who has been at Lincoln High School for 12 years. “Suddenly, we were going to require every kid to take Algebra 2, which is very abstract.”

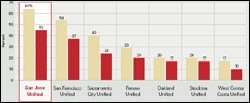

Higher percentages of San Jose students met University of California course requirements in 2002-03 than in comparable urban districts in California.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: Education Trust-West

Now, as the fourth class of seniors to complete the rigorous curriculum prepares for June commencement, San Jose Unified’s strategy for raising achievement offers an instructive example to other districts struggling to fix failing high schools and increase minority students’ graduation rates. The district is also one to watch as policymakers and educators wrestle with the question of what it means to ensure the “college readiness” of high school graduates. (“Views Differ on Defining College Prep,” this issue.)

A half-dozen other California districts are weighing the adoption of the A-G curriculum, while the 727,000-student Los Angeles Unified School District will launch the program with the entering freshmen of 2008.

“San Jose is dispelling some very important myths,” said Russlyn Ali, the executive director of the Education Trust-West, an Oakland, Calif.-based advocacy group that strongly supports increased rigor in high schools for all students. “What San Jose makes clear is that those fears that there’s no way that Latinos and low-income students can cut it in a more rigorous environment are just flat wrong.”

The advanced high school curriculum here in San Jose, where half the public school students are Latino and 40 percent of students come from poor families, has produced promising results.

Graduation rates have held steady despite fears they would plummet under the tougher requirements. In 2004, San Jose Unified’s graduation rate was 93.7 percent, according to the California Department of Education. In Santa Clara County, where nine out of 33 school districts (including San Jose Unified) have high schools, the rate was 91.7 percent; statewide, it was 85.3 percent.

All of San Jose Unified’s racial and ethnic subgroups have made progress toward meeting the district’s rigorous course requirements since the district adopted them in 2002.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: San Jose Unified School District

In 2003, 45 percent of San Jose Unified’s Latino graduates satisfied the A-G coursework with grades of C or better. That rate outstripped that of Glendale Unified, the highest-performing urban district in Southern California, where 17 percent of Latino graduates completed A-G coursework with a C or better, according to data from the Education Trust-West.

Latino enrollment in chemistry and biology courses in San Jose Unified more than doubled from 1999, when fewer than 250 such students took those courses, to 2003, when more than 500 Latino students were enrolled.

But the district’s A-G strategy has cost students some flexibility. They have less time for electives, especially as freshmen and sophomores.

And one key indicator of the curriculum’s success remains stubbornly stuck: The proportion of students applying to four-year colleges hasn’t budged much beyond 24 percent districtwide. By contrast, 64 percent of San Jose’s graduates last year finished the A-G courses, which also meet the minimum course standards for admission to the California State University system.

District leaders began working aggressively on that problem last summer at San Jose High Academy, one of the district’s high-poverty high schools. Using a $1 million grant from Applied Materials Inc., a technology company based in Silicon Valley, the district enlisted help from College Summit. The national nonprofit group, which is based in Washington, works to increase college attendance among students from poor families.

“We target the kids who are midtier academically, those in the 2.0-to-3.0 range, and work closely with them and their teachers on the transition to college,” said Paul Collins, the program director for College Summit in Northern California.

More than 75 percent of San Jose High’s seniors scheduled to graduate this spring have applied to two- or four-year colleges, he said.

A lawsuit, an ambitious community-engagement campaign, and strong leadership have brought San Jose Unified to where it is today.

Twenty years ago, the district was under legal fire for its neighborhood schools which kept poor, mostly Latino students in the worst schools. In 1984, a federal court ordered the district to desegregate and appointed monitors to supervise.

In response, San Jose offered districtwide open enrollment, created magnet programs in its downtown schools, and went through a process of “de-tracking,” so that children of every academic ability had classes together.

Most San Jose students receive high school diplomas only after completing coursework modeled after the minimum course requirements for admission to the 10-campus University of California system. San Jose is the only district in the state, at least for now, that uses the UC standards.

| Years | |

| English | 4 |

| Social science requirement | 3.5 |

| U.S. history | (1) |

| American government | (0.5) |

| Economics | (0.5) |

| Other social science | (1.5) |

| Mathematics (college prep) | 3 |

| (including Algebra 2) | |

| Science | 3 |

| (including two years of lab science) | |

| Foreign language | 2 |

| Visual/performing arts, or applied arts | 2 |

| (Only 10 credits may be in applied arts.) | |

| Physical education | 2 |

SOURCE: San Jose Unified School District

By the time Linda Murray became the superintendent in 1993, the district, she said, still needed to work on the academic-achievement gaps between Latino and blacks and their white and Asian peers. That’s when San Jose Unified became one of six districts in the nation to adopt Equity 2000, a College Board program that put every freshman in algebra or a higher-level math course.

“That really laid the foundation for us to realize that, given the right supports for our kids and professional development for our teachers, we could raise the bar for everyone,” said Ms. Murray, who left San Jose in 2004 to become the superintendent-in-residence at the Education Trust-West.

Ms. Murray and her leadership team also learned from focus groups, surveys, and “community conversations,” that the public believed high school in San Jose was too easy. “The community support was clearly there to raise the bar even higher,” she said.

To make the world of A-G work, Ms. Murray said, the district crafted a menu of programs for students and teachers who would struggle with the change. Up to two additional periods were allotted for the high school day. Special Saturday sessions were created to help to students, especially in math. Summer school was redesigned to be rigorous, not remedial.

And though they intended for all students to obtain a diploma through the A-G curriculum, district leaders realized that some students in special education and alternative programs needed another path. Roughly 9 percent of San Jose Unified’s graduates are taking a more individualized curriculum, such as independent study, though they must earn the same number of credits as their peers.

District officials also opened enrollment in Advanced Placement courses to all students, and watched as a more diverse group of students signed up.

But many challenges remain. Chief among them, district leaders say, is finding highly qualified math and science instructors to teach courses such as physics and AP calculus. This year, for the first time ever, the district offered early contracts to its favored math-teacher candidates who will start teaching this fall.

“A high-level math teacher is like gold,” said William J. Erlendson, an assistant superintendent. “In the Silicon Valley, it’s hard to convince someone with that knowledge to come teach in public schools.”

San Jose Unified has no school-based counselors, so the district tapped teachers and administrators to become students’ academic advisers. At Lincoln High, a one-day-per-week “homeroom” is when teachers, who are assigned groups of roughly 30 students to follow over four years, do the advising. One challenge, teachers say, is battling the immaturity of 9th graders, many of whom think the first year of high school doesn’t count.

“They don’t get it yet,” said Liz Roselman, a French teacher at Lincoln High for 14 years. “You tell them that they are at the start of a four-year graduation plan, and that they can’t take this lightly.”

For Monica PĂ©rez, who would be the first in her family to go to college, the A-G curriculum is providing her the necessary preparation.

“It’s not easy when you’re the first, and when there is no one in your family that’s been through it,” she said of pursuing higher education. “But being in a high school that demands more of me is going to get me there, hopefully to Juilliard or [New York University].”