69��ý in most states can earn a distinction on their high school diplomas that acknowledges their proficiency in English and at least one other world language. All 50 states and the District of Columbia now allow districts to offer this distinction, called the seal of biliteracy, for students who pass a language assessment.

But what if there is no available assessment for a language a student has learned?

Take Karen. The language, with various dialects, has been banned in public schools in Burma since the 1960s, when the military staged a coup, said Megan Budke, the immersion, indigenous, and world languages coordinator for the St. Paul public schools in Minnesota. (The military renamed the country Myanmar in 1989.)

Yet Karen (pronounced ka-RIN) is a home language to many students in the district in Minnesota’s capital. More than 2,000 St. Paul students culturally identify as Karen, Budke said.

Shortly after the biliteracy seal became available to Minnesota students in 2015, St. Paul district leaders, state leaders, and a national language organization came together to develop an assessment for the language, which is indigenous to southern Myanmar and bordering areas of Thailand.

Since then the St. Paul district has worked with university partners and families to develop a Karen-language program and a pathway to license teachers of Karen and other less commonly taught world languages.

Their efforts highlight one way in which the seal of biliteracy can be more than an endorsement on a diploma. It also can serve as the impetus for districts to develop additional language offerings that reflect their communities.

“As public school systems, we like to say on the surface we value students to show up as their whole, authentic selves. But then we put them in a school system that is 100 percent English, or we offer world language courses, but none of them are actually in their language,” Budke said. “I think that’s really hard on students.”

How the seal of biliteracy can promote language programs

The seal of biliteracy started as a grassroots effort to recognize the language assets of English learners. But some researchers say schools can also use the seal to bolster the language abilities of heritage speakers—students who speak a language other than English at home but were never identified as English learners.

, Samuel Aguirre—director of WIDA Español, a part of the consortium that assesses English learners’ English-language proficiency—and other researchers found that only five of the 39 states providing data actually tracked how many seal recipients were heritage speakers. Those states were Indiana, New York, Ohio, Utah, and West Virginia.

It’s a data gap Aguirre and others hope other states address as more students earn the seal.

In St. Paul, breaking down seal of biliteracy data by heritage speakers proved necessary for designing the Karen-language course. Budke noticed that heritage speakers of languages initially not taught in the district were less likely to earn a seal of biliteracy and also less likely to earn higher-level distinctions tied to the seal. In Minnesota students can earn a certificate, a gold seal, and a platinum seal, the highest level.

This discrepancy, along with families requesting formal Karen instruction, prompted the creation of a high school level Karen-language program, Budke said.

Launching that program required creative thinking and strategic partnerships.

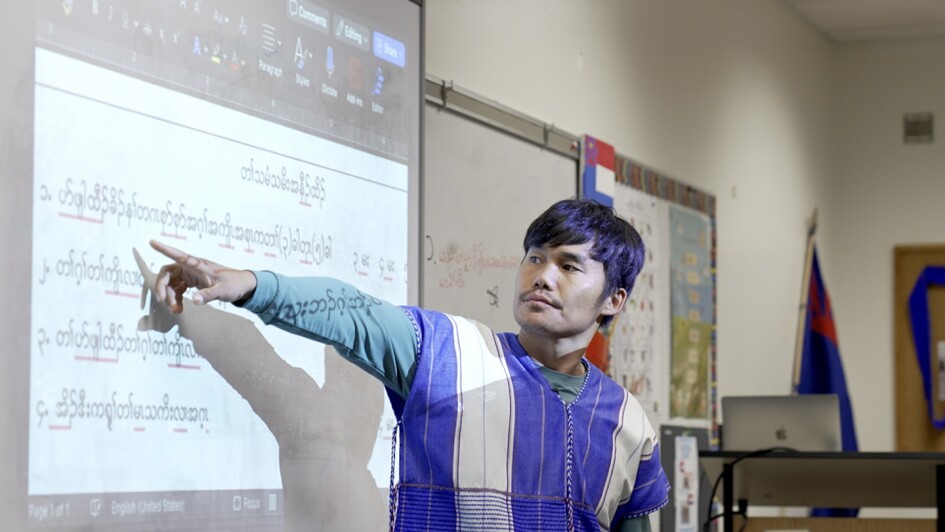

Budke and her team initially brought together Karen-speaking staff—including existing teachers and bilingual educator assistants—and community members. They helped guide the curriculum design, which led to the creation of two course levels: one for students who were fluent in listening to and speaking Karen but required reading and writing instruction, and another for beginner students.

Given how little formal Karen instruction exists in schools anywhere in the world, St. Paul teachers had to be resourceful in assembling instructional materials, Budke said.

They bought some books from an organization in Thailand that is teaching Karen in refugee camps, cobbled together internet resources including YouTube videos, and even recorded themselves and other community members speaking and reading text for students to recognize Karen in various accents and dialects.

The St. Paul district also partnered with Concordia College in Moorhead to create a licensure program for Karen-language teachers, Budke added. The partnership also offers licensing in other less commonly taught world languages, including Hmong and Somali. (The Twin Cities in Minnesota are home to large Somali and Hmong populations.)

Why investing in students’ home languages matters

To researchers like Aguirre, programs like St. Paul’s Karen high school courses help validate students and their families’ cultures in a school environment, which can lead to better engagement in school.

While Budke has seen such validation in St. Paul, she’s also found an additional benefit to investing in new world language programs: stabilizing enrollment.

After about six years of districtwide declines, enrollment stabilized in the 2023-24 school year.

The largest growth came in schools focusing on language immersion and world cultures, . Those include a Spanish-immersion academy, a Mandarin-immersion academy, and an East African elementary magnet school that focuses on Somali, Amharic, Oromo, Tigrinya, Arabic, and Swahili languages and cultures.

Since the Karen-language program launched in the 2023-24 school year, Budke has also seen growth in the number of students earning a higher-level seal of biliteracy.

The district’s goal for Karen-language instruction now is to expand it to the elementary and middle school levels, Budke said.

At a recent school board meeting where members discussed the expansion of the Karen program, an overflow crowd featuring Karen community members stood in the conference room where board members meet, the hallway, and next door in the cafeteria.

“It was such a beautiful thing to see them overflowing the room, because you can just see this was really important to them,” Budke said.