(This is the first post in a two-part series)

The new question-of-the-week is:

How do you integrate writing in science classes?

Writing is a critical skill for students to learn, and its development does not have to be limited to English class.

This two-part series will discuss what role writing should have in science classes.

You might also be interested in this collection of resources: .

Today’s guest are Mary K. Tedrow, Amy Roediger, Dr. Maria Grant, Diane Lapp,EdD, Mandi White, Tara Dale, and Becky Bone. You can listen to a I had with Mary, Amy, and Maria on . You can also find a list of, and links to, By the way, you can also now listen to the show on and , in addition to iTunes.

Response From Mary K. Tedrow

Mary K. Tedrow is a veteran English teacher and the Director of the Shenandoah Valley Writing Project. Check out her new book, :

If summative writing--lab reports or research products--is the only writing students create, science teachers will be frustrated by inadequate products. Expanding writing into regular, writing-to-learn practice helps students focus and practice thinking, absorb content, and manipulate new concepts long before a grade.

Frequent, ungraded, easily shared, and informally assessed writing builds content area understanding while improving fluency: the ability to produce written thought without fear or anxiety.

Writing in science should mimic writing done by scientists. For instance, at the course beginning ask: “How do you know something is true?” 69��ý write individually before sharing with partners. Spark a class discussion and develop rules for truth-finding by asking “Let me hear your thoughts.” Post rules in student language and build a classroom culture dedicated to a search for truth.

Turn classrooms into inquiry spaces by prompting What do you notice? to record observations after demonstrating phenomena or observing natural events. This question has no wrong answer and continued practice builds observational powers. By sharing writing with peers, students learn what to look for or what was missed. Follow the event, the prompt, and discussion with writing time to record “What questions do you have?” Unit instruction can build from natural curiosity.

After labs or demonstrations, require reflective writing. Ask students to record “What did you do? What happened? What does it mean? and What should happen next?” These informal questions are accessible and prompt students to write in a non-academic voice while thinking like scientists. First writings will be expressive--recording the inner voice.

Rather than turning every reflection into a lab report, collect many observations over time so students can choose from among experiences.

Require fewer transformed into a formal report that demonstrates skill around required formats. Allow students time to check each other’s, offering feedback on format and content. This reflects the social nature of real-world writing where teams of people--editors, friends, colleagues--contribute to writing before publication. If report numbers are reduced, class time can be repurposed for students to work collaboratively, digesting requirements, rather than repeating mistakes. With choice, students are more likely to succeed.

Writing prior to lessons gets students ready to learn. The best prompts offer choice that leads to personal connections. Good prompts start “Think about a time when....” For instance, “Think about a time when you noticed a weather event. What happened? What reaction did you have to the event? Did it make you wonder about anything?” Share so students learn from and about each other.

When lecturing, cut information into short segments. Stop so students make rather than take notes. Follow with sharing so students can harvest and correct information. Material is reviewed three times: lecture, note making, and sharing and adjusting notes.

These management tips keep everyone working:

Use a timer. Teach students that writing time is quiet time. No talking while the timer runs.

Write with students. Occasionally share your writing. They will learn about you while your model supports the process.

Collect writing in a notebook. Use the notebook for sharing, quizzes, a resource for formal writings, and a record of growth.

Train students to just read what they wrote. It’s faster and they begin to hear a writerly voice.

If needed, grade low-risk writing only for participation. 69��ý can flag entries as evidence of learning for quick spot checking.

- Correcting non-standard English should be reserved for summative products that follow drafting, revising and editing--just as it is for real writers.

Response From Amy Roediger

Amy Roediger is the Science Department Chairperson and an instructional coach at Mentor High School in Mentor, Ohio. She was recently recognized with the Presidential Award for Excellence in Math and Science Teaching. A Google Education Trainer and NBCT, she is passionate about meaningful integration of classroom technology. She blogs about that and more at .

Written communication is a vital component of science, so students must practice concise, evidence-based writing in science classes. In my classes, I try to regularly incorporate writing into most tasks with short answer questions embedded in tests, quizzes, and labs. These questions provide opportunities for students to describe scientific concepts and apply course content to real-world situations.

About once a month, my students write a formal laboratory report to document their findings after an inquiry experiment. These reports include a discussion of the lab concept, a summary of the procedure they used, a data table for all the measurements, necessary data analysis, and a conclusion. I evaluate each section on a five-point scale and add the points to get a total score. Though the subject matter of each laboratory assignment varies, the rubric that I use to evaluate each one does not.

With the emergence of the Common Core State Standards and next-generation assessments, I wanted to tie the writing my students do to broader expectations for writing. Rubrics are available for PARCC and Smarter Balanced writing assessments and can easily be adapted to score scientific writing. My state uses its own graduation assessment, so I modified the rubric from that test. Consistent use of an adapted rubric provides students with extra chances to practice the important work that begins in ELA classes. Using these skills outside of English class increases the likelihood that they will become habits of mind.

Whether or not a teacher is willing to adapt a national or state assessment rubric to fit their classroom science writing, purposeful collaboration with our ELA colleagues provides a common language that drives instruction in all subjects. Hopefully, we all agree that the basic tenet of good writing is to state a claim and support it with evidence. What could be more scientific than that?

Response From Dr. Maria Grant & Diane Lapp, EdD

Maria Grant, EdD, is a professor of secondary education at California State University, Fullerton and is also a teacher-coach at Health Sciences Middle School and High School. She can be reached at mgrant@fullerton.edu.

Diane Lapp, EdD, is a Distinguished Professor of Education at San Diego State University and is also an instructional coach at Health Sciences Middle School and High School. She can be reached at lapp@mail.sdsu.edu and followed @Lappsdsu:

Writing in the Real World of Work

A question often asked since the release of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) is how to teach students to read and write within the discipline of science? The simple answer is to teach them to read and write like a citizen interested in being informed about scientific topics and also like a person who may eventually work in science. Since scientific information is shared by popular press writers and professionals working in the discipline, students should be taught to read and write like both informed citizens and also future workers in scientific fields. Realizing this, there are a few, very specific aspects of writing that educators might consider when teaching students to compose science-related pieces.

What type of science writing are you targeting?

First to consider is the type of science writing that is targeted. There are many ways that writers can convey science ideas to audiences and even within this genre, there are variations. Today’s science content, written for the general public and for the work place, use different styles, tones, and language patterns and structures.

Science Writing for the General Public

Consider the numerous science blogs and websites that the general public peruses on a daily basis. The tone is typically more casual and may even use active voice, instead of passive voice- a way of writing that was once taboo in many corners of science. With a growing interest by the public and young people to know more about world issues rooted in science, being able to convey ideas in a compelling, approachable manner is essential. Many voices are being heard through scientific writing including those of researchers or a formally trained ‘science person’, as well as the knowledgeable citizen who wants to have a voice in critical issues of the day as they talk about genetically modified foods, global climate change, ocean acidification, energy in society, as other areas of interest like invasive plant species over-running native plants in our national parks or niche areas of interest like bird song composition or beekeeping tips. This kind of science writing is broad in scope, exciting in topic, and relatable to every person on this planet. It’s about us, and the world we live in.

Science Writing for the Science and Engineering Workplace or Field

Science writing in the workplace often involves discipline-specific tasks requiring specific science skills and understandings of science literacy, coupled with science knowledge. Writers of science for the workplace or the field need experience with interpretation of science texts using the skills and criteria that would be used by a science expert (Wolsey & Lapp, 2017). They must study lab reports, journal articles, graphs, charts, and other discipline-specific texts to learn how to create their own using the same criteria (Shanahan & Shanahan,2008). In essence, they go beyond general expertise in writing to compose texts modeled after those of the experts. For example, students writing for readers of a science journal or composing a lab report would be using a concise style of writing, with appropriate academic and technical language, often using passive voice, and including references to data, analyses, and conclusions. The tone is formal and technical.

Developing Skills to Write in Science

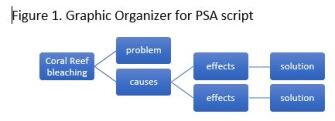

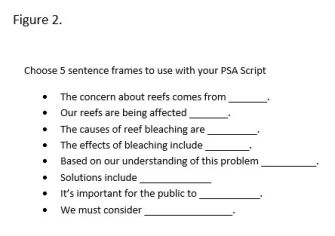

Writing for the general public requires knowledge of the science content being conveyed and it also requires expertise in content area literacy. As an approach, students can use many of the same general literacy skills that are taught across disciplines. Consider the following instructional practices used by Mr. Lopez, teacher of 9th grader, David, who has tasked his students with writing a Public Service Announcement script for a commercial warning about the bleaching of coral reefs in the Great Barrier Reef. To compose his PSA, David closely read three articles on the topic of reef bleaching, made annotations with each read, and engaged in lots of small group conversations around the readings. His teacher asked him and his classmates to create graphic organizers to set up their PSA text. Mr. Lopez then offered sentence frames to get them started (figure 2), and instructed them to make the PSA compelling and engaging. The goal was to inform and to inspire action on the part of the public. The skills needed and the subsequent instruction offered are content literacy strategies that cut across many disciplines. 69��ý complex texts several times, annotating, engaging in conversations around content, creating graphic organizers, and using sentence frames are all well-founded, research-based strategies that work well for science writing that is intended for a general public audience.

Writing for the science workplace or for the field of science should involve instruction that follows a more discipline-specific route. Consider Ms. Williams’ high school physics class in which students are tasked with presenting a proposal for their design of a well-lit, functional library to be located in the center of town. The presentation that includes a written proposal with visuals will be shared with an engineering firm that wants to hire a new team for the job. The proposal is for a targeted science-engineering expert audience, so the instruction has to focus on content knowledge as well as discipline-specific presentation means, including science-style writing, augmented with schematics and architectural design diagrams.

To help students learn about this, Ms. Williams presented them with sample proposals of building designs acquired from city records for their review. She engaged them in think-alouds during which she showed how an expert in science and engineering thinks about the plans, articulating ideas like, “I notice that the proposal includes technical terms like ...... and the text references the circuitry schematics on page 2.” She then had students practice interpreting other diagrams with partners. They compared different proposals from other cities to see what had the most appeal to city planners. They reviewed design constraints and building laws, noting requirements on documents they referenced when composing their proposals. They utilized observation and analysis skills, and drew conclusions using a lens of inquiry to investigate other proposals before drafting their own. Using a science criteria rubric (Figure 3), they evaluated their own drafts before finalizing and presenting to a mock engineering firm.

The Bottom Line

Writing in science today takes various forms. If we want to empower our young people to have a voice in today’s issues related to science, they must know how to convey their thinking in written form. Being scientifically literate entails being able to write about science for the general public and being able to write for the workplace. When the audience is different, the writing is different. While general content literacy instruction can often support writing for the general population, specific science writing skills are needed to communicate with professionals in the field. Teachers can employ the tools necessary to equip students to articulate their understandings in appropriate, meaningful ways that can be faciley interpreted by the intended audience. Science writing proficiency empowers young people to have a voice about issues of great import. Teaching students to be articulate, thoughtful, and informed science writers is the challenge and the duty of all great educators. It’s time to meet the challenge!

Shanahan, T. & Shanahan, C. (2008).Teaching disciplinary literacy to experts. Rethinking content area literacy. Harvard Education Review. 78, 40-59.

Wolsey, T.D. & Lapp, D. (2017). Literacy Beat.

Response From Mandi White & Tara Dale

Mandi White earned a Master’s of Education in Special Education from James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va. In 2007, she moved across the country to begin her teaching career in Phoenix, Ariz., as a cross-categorical resource teacher for 7th and 8th grade students. Mandi began her new position as an academic and behavior specialist in July 2017.

Tara Dale is a high school science teacher in the Gilbert School District in Arizona. Previously she taught 7th grade science and U.S. history in Phoenix. She was recognized as Kyrene’s Educator of the Year at the end of her second year teaching and then two years later was honored with the Science Foundation Arizona’s Innovation Hero Award. In 2014 she was named Arizona Teacher of the Year Ambassador for Excellence. She travels the state advocating for Arizona’s teachers and students with her work at Educators for Higher Standards, Student Achievement Partners, and Arizona Educational Foundation:

“But Teacher, this isn’t English class, it’s science class!” Our students make what they believe to be is an intellectually deep point while arguing with us about the amount of writing we require them to do. Our response is always the same when this age-old disagreement begins, “But scientists enjoy being paid for their work and if they don’t communicate their results, they receive no money. This is why writing is required for both the scientific method and inquiry process.” End scene. Mic drop.

Scientists write all the time but the most important writing they do is when they’ve discovered an anomaly and must communicate it. Can you imagine the violence that would erupt if a scientist discovered the cure for all cancers and then never wrote about it, kept the secret to herself, and allowed people to die? It would be inexcusable and deplorable.

As science teachers, we must insist students practice writing, provide students with feedback about their writing, and require students to publish their writing.

Writing lab reports is essential because it’s excellent practice for college and career bound students; however, there are other types of writing that can be done in a science classroom. For example, students can write perspective stories, describing their journey through the digestive system as they pretend to be a bite full of food. Or they can write children’s stories about the moon or ocean. 69��ý can also write persuasive letters to local businesses challenging owners to make environmentally-friendly decisions.

Writing assignments can be time consuming to grade so minimize your time commitment but choose one focus. Do you want your students focused on practicing new vocabulary and concepts, using data to justify their hypotheses and conclusions, or writing in a coherent manner with topic sentences and proper spelling? Not every writing assignment has to focus on every important science and writing lesson. The most important and efficient way to use writing in science classes is to spend the least amount of time grading and the most amount of time providing specific feedback so students can learn from their errors.

Many science teachers have embraced the and if you are one of them, then it’s easy to incorporate writing into your classroom. There are writing opportunities at every E, especially when students are elaborating and evaluating. This is a great place for students to write lab reports but there are many other opportunities; for example, students reflect on their learning, ask questions to continue the experimental process, and extend new concepts and skills.

Resources available for teachers include to Integrate Writing into the Science Classroom, the NSTA’s , and the (segmented by grade level). We challenge you to find a new way to incorporate writing into your science classroom that is engaging and dynamic for your students.

Response From Becky Bone

Becky Bone is the vice president of professional learning services for scholastic education, and consults with school districts nationwide on K-12 literacy and professional learning initiatives. She received her undergraduate degree from the University of Florida and graduate degree from the University of Central Florida. Becky also has served as curriculum coordinator in the Central Florida area:

As many teachers use small guided reading groups to differentiate instruction and teach the specialized ways that science texts work, the same can be done for students learning to write about science. What better way to learn models for scientific writing than to extend small group guided reading instruction to small group guided writing instruction? As Timothy and Cynthia Shanahan have argued, ideally, instruction should help students understand the different ways that literacy works across content areas (“What is Disciplinary Literacy and Why Does It Matter?” Topics in Language Disorders, 2012).

Jan Richardson (The Next Step Forward in Guided 69��ý) explains that when students write about what they read, it supports their comprehension of the text. Guided writing also helps students improve writing skills during small group instruction with teacher support. With coaching and scaffolded instruction, guided writing and content-area instruction can support and enhance each other.

Richardson suggests a four-step process:

To begin, a teacher can select a targeted science-writing skill from student work. Examples might include: paraphrasing the science concept, explaining the steps of the science lab, or providing supporting evidence from the text.

Next, select a response format that is challenging for the small group (since the teacher is scaffolding writing instruction). Ideally, the writing task will connect to the focus of the science text used during the guided reading lesson.

Once the response format is selected, model how students could draft a simple plan or concept map using key words and phrases from the text. Plans could be a compare-and-contrast graphic organizer, or a main idea/details graphic organizer.

Now, you are ready to scaffold students as they write. You can prompt them with their science writing/response to writing as needed. For example, if they need to work on using domain-specific/science vocabulary, you might prompt students to avoid using common words and encourage them to use the content-specific vocabulary from the text.

Or if students are struggling with the introduction, and you want to teach them to use key words, ask: What are the key words in the writing task/prompt? How can you use some of those words in your first sentence? If their writing needs work on focus and organizing ideas, scaffold instruction to create a “key-word plan” before they write. Coach students to check off those key words from their plan as they appropriately use the words in their writing.

Think of integrating writing into science classes (or any content area) as an opportunity to go deeper with your instruction! When teachers provide guided writing instruction that incorporates the specialized nature of content-area texts, student achievement in both writing and science will soar.

Thanks to Mary, Amy, Maria, Diane, Mandi, Tara, and Becky for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at .

Anyone whose question is selected for this weekly column can choose one free book from a number of education publishers.

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching.

Just a reminder—you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via or And, if you missed any of the highlights from the first six years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. They don’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

I am also creating a .

Look for the next Part Two in a few days.