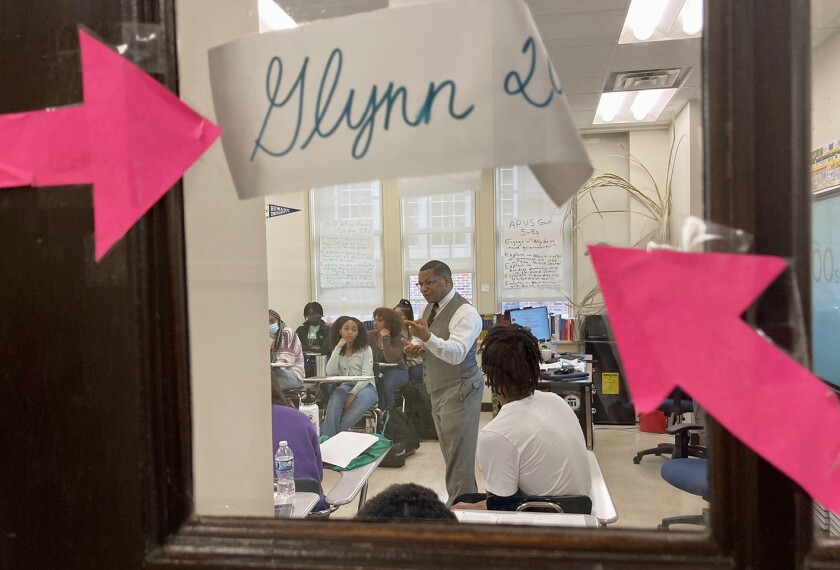

In the Advanced Placement American Literature course I taught for a decade, my students and I spent our time reading and analyzing writers who have been given a stamp of approval by being âcanonizedâ for embodying the American story, struggle, and spirit. I always taught my students that it was important to situate our reading within the greater context of American history. âWhose story is being told?â âWhose stories are not reflected on these pages?â Those questions often prompted me to pull in additional standards-based texts so that we could, indeed, understand the full American story.

This past fall, I learned that the College Board was piloting an AP African American Studies course. This gave me hope that students would now learn some of the content pivotal to the American narrative that had been excluded from the traditional American literary canon.

I was encouraged by the thought that this history that is often seen as tangential to American history, to the American spirit, would finally be studied by young people across the country. For far too much of their K-12 experience, many students have only seen African American history treated as a subset of ârealâ history.

But when Florida Gov. Ron DeSantisâ administration announced last month that AP African American Studies would not be taught in the state, my first question was, âWhy not?â Remembering how well-sourced the College Boardâs content is from my own certification process to teach an AP course, I was skeptical that the Florida education department determined that the course was ânot historically accurateâ and that it âsignificantly lacks educational value.â

AP African American Studies isnât under fire for inaccuracies. On the contrary, the course is being banned because the content is accurate and valuable.

The ongoing rejection of African American history in Florida and many other statesâincluding my own state of Texasâis a rejection of the stories that have been erased from the K-12 learning experience. It is a rejection of the struggles of Americans whose resistance forced this country to admit through new laws and constitutional amendments that our racism and discrimination were in conflict with our own stated values. It is the rejection of the lived experiences of the 7.4 million Black students in U.S. public schools, who need to learn how inextricably linked the work of their ancestors is not only to the work of Black people today but also to any progress that we label âAmerican.â It is the absurd promise that the millions of students in our classrooms will one day inherit a country without knowing the full history of it. The irony is scary.

But however scary, this resistance to teaching students our shared history is not inevitable. Gov. J.B. Pritzker of Illinois recently wrote a letter to the College Board rejecting modifications to the AP African American Studies course. I hope that many other governors follow suit. Shrinking from the truth has never led to progress for all Americans.

Denying access to information does not lead to the preservation of democracy. In fact, access to information is a prerequisite for children to practice inquiry and the discourse they will need to exercise in society.

The DeSantis administrationâs rejection of this course sends Floridians the message that African American history is âother.â It tells them that learning about the experiences of millions of Black people who helped build this country is more dangerous than learning a history that romanticizes the deeds of the colonizers and secessionists who continue to be celebrated in the curriculum and with monuments.

The greatest irony of all is that rejecting this history does nothing but hurt young people while legislators claim to be their saviors and protectors.

One thing I always told my students is that what the literary canon and history books include and what they leave out will always tell us who and what is considered important. Children who donât see their stories in the curriculum will, in turn, feel disconnected from the learning process.

States, districts, and educators should look at the curriculum to determine whether it shrinks or expands knowledge, includes or excludes perspectives, erases or writes full history.

Itâs only when we begin to have greater representation of all Americans in our academic content that we can say we are preparing children to be critical thinkers who will simultaneously love this country and demand it to do better for all citizens.