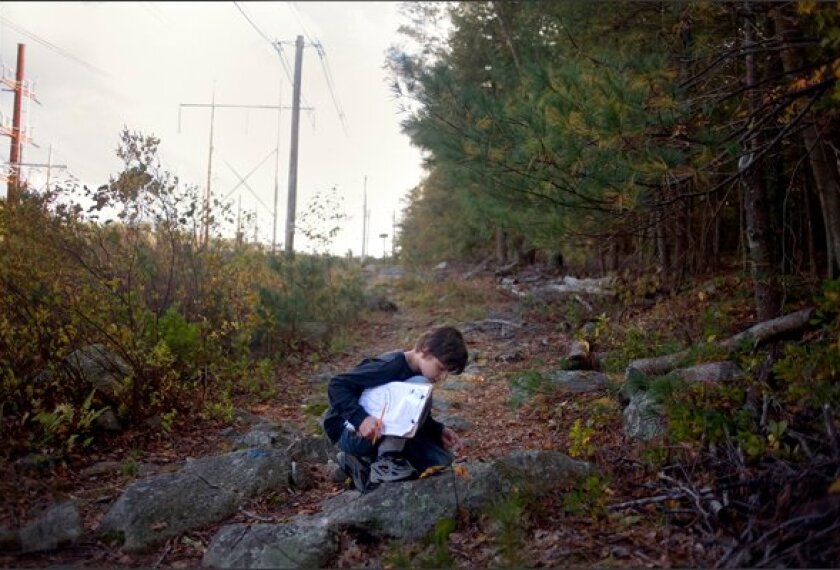

About 50 6th graders at Roger Williams Middle School hiked with the Audubon Society during a class period last week, examining plant and insect species and cataloging birds from a nearby urban park. For another period, they gathered water samples aboard a boat on Narragansett Bay.

Those experiences were part of their new 7th-period class, which adds an extra hour to the school day, five days a week, focused on building student competency and a deeper understanding of the STEM subjects—science, technology, engineering, and math. For two of those weekly periods, the students venture outside the walls of the Providence, R.I., school for field-based learning experiences led by their teacher in conjunction with community providers.

On the other days, the 7th period is reserved for an added hour of instruction related to the experiences they have off campus, taught by their teacher and an AmeriCorps member. Last week, students spent the extra in-class periods classifying the insect and plant species they found on their hike and peering through microscopes to look for plankton in the water samples they collected.

Providence’s expanded-school-day pilot is a partnership between the school district and the , a nonprofit that manages after-school programs for low-income students in that city. Their efforts come alongside growing national interest in expanded learning time, or adding time to the school calendar as a way to help low-performing students catch up.

But while policymakers and recently proposed federal legislation promote expanded learning time as a strategy for school turnaround, some worry that it may be gaining steam too rapidly as a fix for schools that lack the know-how, resources, or research to implement it effectively.

According to Hillary Salmons, the executive director of the alliance, Providence is taking small steps first.

“Quite honestly, there is no way with our economy that we could robustly afford to expand the school day for all of our kids,” Ms. Salmons said. “For this model to be scalable, we need to be strategic with limited funds. Expanding the day for learning is going to have to be staged in building blocks with a good mix of proven practices and a match of resources and priorities.”

New Models

A number of schools in the Houston district were listed on Texas’ “academically unacceptable” list and faced penalties if they didn’t start improving. As a solution, Houston adopted strategies from high-performing charter schools for its , launched last year.

Nine middle and high schools added five days to the year and an hour of instructional time to the day, four days a week. A new principal was installed in each school, and more than half the teaching staff and a third of the administrators were laid off and replaced. More than 257 math tutors were also hired at a base salary of $20,000 to work one-on-two with students.

Before school started this fall, the 204,000-student district reported academic gains in the nine participating schools after one year of implementation, according to an evaluation of the program by a Harvard University economist. Math scores, on average, improved equivalent to an additional 3½ months’ worth of material. 69��ý scores increased minimally, however. This school year, every school in the district added five days to the year, and 11 elementary schools are increasing their instruction time on math and reading each day.

Whether the Apollo initiative will be sustainable or the results long-lasting is unclear. Financial support for the program (primarily for the tutors), comes from a combination of public funding and private dollars and supports three years implementation.

Houston is one of several large urban districts that are expanding the learning day. Boston has a number of expanded learning schools, many of them part of Massachusetts’ Expanded Learning Initiative, which uses state funding. And Chicago is feuding with the local teachers’ union over lengthening the days at a few schools this year, with the district seeking to move to a longer day at all schools by 2012-2013.

But these expanded learning time, or ELT, efforts have some questioning if added school time really has an impact on students, and whether schools will be able to use added time effectively to improve student outcomes.

Elena Silva, a senior policy analyst at the Washington-based think tank , says there is a lack of research-backed examples of high-performing ELT schools that others can look to for guidance. While charter schools and schools in Massachusetts have been able to use the strategy effectively, she said, the average school would face different circumstances and concerns in implementing extended-day models, primarily around funding, staffing, and programming.

“Right now, some see ELT as a simple reform, that it requires X dollars and X minutes. But time is not a single reform; it is a tool connected to others,” Ms. Silva said. “More time can be a useful tool to help close the achievement gap, but there is a risk that it could be another passing reform that we will adopt when we have money, but drop when the budget is tight.”

, a Boston-based organization that grew out of Massachusetts’s ELT efforts, is tracking and evaluating expanded learning ventures nationwide. The organization recently released a best-practices report, based on assessing 30 of the “best” ELT schools in the country.

The center estimates that 1,000 schools around the country currently have expanded-learning-time models, but not all models are high quality, and those that aren’t tend not to see academic gains and improvements.

But according to the , while attention to a lengthier calendar is growing, the number of states requiring more than 180 days is the same this school year as it was in 1980: three. In fact, more states have allowed districts to reduce days for fiscal reasons: two states allowed districts to go fewer than 175 days in 2000, compared with eight this year. In the past year alone, 120 districts in 17 states went to a four-day week to save money, the Denver-based ECS reports, though the savings were small.

Still, districts in Florida, New York, and elsewhere are trying out expanded learning time as a turnaround strategy, some with the assistance of intermediary organizations like Citizen 69��ý and The After-School Corporation. And some states, like Colorado and West Virginia, are investing in research to determine whether expanded learning is an effective use of funds. More states may consider extending their school days in the future, however, since the Elementary and Secondary Education Act reauthrization bill in the U.S. Senate and the Obama administration’s No Child Left Behind Act waiver plan encourage the strategy for school turnaround.

Defining the Reform

While most advocates of expanded learning agree that added time should be used to meet the needs of individual schools, they also agree that it’s not just about adding time to the day, but also what is done with that time.

To implement high-quality models, the whole school needs to examine how it’s already using time, said Frederick M. Hess, the director of education policy studies at the Washington-based American Enterprise Institute and an .

“We need to make sure we’re doing all we can to use time smarter and more efficiently before simply demanding more of it,” Mr. Hess said. “It’s going to take a lot of thought and care for ELT to deliver. Otherwise, what may be a great idea in the hands of KIPP [the Knowledge Is Power Program charter school network], or a smart move at schools partnered with Citizen 69��ý, could be a waste of time and money and a recipe of added drudgery for teachers and kids.”

For many schools, that would involve a full redesign around how time is spent, something many expanded-learning-time leaders say is necessary to drive school improvement. Yet for some schools, both designing and implementing such models could be a challenge, particularly with limited research.

Some, like Providence, have turned to the research that exists on quality out-of-school-time programs as guidance for what to do with added time rather than doing “more of the same.”

The ELT initiative at Roger Williams draws on the academically enriching curriculum of the Providence alliance’s well-regarded after-school and summer programs that have been found to improve behavior, attendance, and grades, based on the results from a three-year longitudinal study released by Public/Private Ventures this past summer. Although after-school programs have typically worked outside the traditional school day, some educators see the style and substance of the best out-of-school programs as a good way to use the added hours in extended days.

“There isn’t a lot of research that says a longer day is what makes a difference, [but] there is a lot of research that says after-school programs partnering with schools is an effective model,” said Priscilla Little, a Boston-based independent education consultant and a former researcher with the . “I would love to think that the notion that there is a school and an after-school goes away, and instead, there is rich learning that goes throughout the day and throughout the year.”

Commitment Lacking?

But while the structure is one hurdle, the amount of money and staff to support ELT models is another.

A number of schools with expanded-day models have used one-time School Improvement Grants, to jump-start programs, but given the current patchy state of school budgets, sustaining them could be a struggle.

Nevertheless, ELT supporters are optimistic that the concept is financially feasible, particularly by turning to private resources and innovative staffing models to ease the financial burden. Partnerships with community providers, a common feature of out-of-school-time programs, has been a cost-effective solution for some districts who often use the providers as “second shift” educators.

That’s the case in Providence, where the transition to an extended-day program with community educators was the most feasible and affordable option for the district rather than hiring more teachers or paying higher salaries for teachers to teach longer days.

For some ELT proponents, a true expanded-learning-time model needs to be mandatory for all students in a school, with at least 300 additional hours a year to support academics, enrichment, and teacher professional development.

Others disagree, citing models that aim to provide new and different experiences within and outside classroom walls for all schools in a district, some schools in a district, or some students in a school.

Last year, Colorado commissioned an evaluation of how to use time and resources to provide students with more flexible, engaged, and enriched learning opportunities. The findings, which urged the state to look “beyond classrooms, class schedules, and the school year,” will be incorporated into a new state project with several districts, supported by the Ford Foundation.

And in New England, districts are working with the Nellie Mae Education Foundation to develop learning models that take place beyond the classroom and traditional school day.

“The whole idea of ‘space’ is emerging that kids can do bona fide, credit-bearing academic work outside of the school building and make much deeper connections to their academic pursuits,” said Robert Stonehill, the managing director of the , a Washington-based nonprofit that conducts after-school and expanded learning projects for the U.S. Department of Education.

“I think there are a lot of strong experiments going on, but right now, I don’t see a real commitment to implementing expanded learning on a broad scale,” he said. “What I think is the issue for the future is not the cut-and-dried issue of schools’ staying open longer, but of schools’ connecting kids to the best possible opportunities, in or out of school, and during or after the regular school day.”