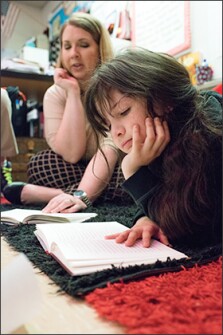

On a February morning, 3rd graders here at Bellaire Elementary were discussing types of surprising treasure found in the novel Treasure Island.

Their teacher, Meredith Starks, confidently navigated through the 50-minute lesson that ended with students writing a paragraph about how a modern-day ātreasureā would surprise a pirate. (One studentās answer: A pirate might mistake a jet plane for a flying dolphin.)

Starksā ease with the lesson isnāt surprisingāafter all, she wrote the curriculum that is now being used across the state.

Starks is one of the more than 75 teachers who have been selected by the Louisiana education department to write an English/language arts curriculum. While most states using the Common Core State Standards tend to look to commercial publishers for standards-based curricula, Louisiana educators couldnāt find material that fully and coherently represented the now 7-year-old ELA standards.

āWe just decided ... there wasnāt anything on the market good enough for our teachers,ā said Rebecca Kockler, the assistant superintendent of academic content at the state education department. And who better to fill that void than actual teachers?

The state started developing its ELA curricula, in 2012, and the first iteration was published in April 2014. Louisiana has since and revamped the guidebooks to give teachers more resources.

Guidebooks 2.0 was released last year for grades 3-12. There are between one and five ELA units for each grade; more are rolling out later this year. Each unit corresponds to grade-level texts and includes assessments, supplementary materials, and 30-50 individual lessons.

The guidebooks, which are freely available to anyone in Louisiana and beyond, live on a cloud-based platform and come with ready-made slide shows, thanks to the stateās , a website with common-core-aligned resources created by teachers.

While the curriculum is optional for districts, Kockler said more than 80 percent have opted to use the guidebooks in some form, either as a complete curriculum or a support resource for their teachers.

Louisiana already appears to be seeing some promising signs of success from the teacher-made curriculum. The most recent state test results showed that students improved performance in reading and math.

And an October study from the RAND Corp. found that in ways that are more aligned with the common core than teachers in other states.

Teachers in Louisiana were significantly more likely to ask students to use evidence from a text, for example, and their students spent more time reading texts that were at grade-level, said Julia Kaufman, one of the reportās authors.

āWe donāt have really clear evidence that ties the use of this teacher-developed curriculum to those practices,ā Kaufman said. āBut we have to assume thatās a big reason.ā

To Starks, it makes sense that the teacher-made curriculum would lead to student achievement and a deeper understanding of the more-rigorous standards. The guidebooks are designed to engage students in meaningful discussions with meaty texts.

āI feel like my lifeās passion is to get textbooks out of teachersā hands and say [to teachers], you can do so much more,ā she said.

Once, she received an email from a teacher across the state who said her 4th graders loved the Whipping Boy unit, which Starks wrote. The teacher put a stick-figure picture of Starks on her board. āEvery time my kids are really super engaged in something,ā the teacher wrote, āwe always stop and say thank you, Mrs. Starks, for writing this awesome unit.ā

An āOrganicā Lesson

In a 4th grade classroom at nearby Curtis Elementary, which is also part of Bossier Parish schools, Kara Stephenson was teaching a . As Stephenson read aloud from the book, George vs. George, she also held her provided teaching notes, which were highlighted and marked with colorful sticky notes.

The ELA guidebooks come with teacher notes that include suggested times for each section of the lesson and explicit directions for how teachers can lead class discussion, including examples of class-discussion questions and āstudent look-fors,ā which allow the teachers to gauge studentsā level of understanding and engagement.

āAs long as [teachers] know the unit, they donāt have to read these things verbatim,ā Starks said, adding that she knows teachers who are asking every question listed in the notes. āMaybe after the first year, when theyāre more comfortable with the lesson, they wonāt have to refer to this so closely.ā

While Stephenson said she doesnāt adhere entirely to the teaching notes, they have been helpful. Between the LearnZillion slides and the teaching notes, she said, she feels like she has a solid base for her lessons that gives her more time to focus on finding high-quality supplementary materials.

On this day, one lesson objective was to learn academic vocabulary within the text. As Stephenson read aloud, she paused to lead class discussions on vocabulary words like āunravelā and āconvinced.ā Stephenson also had an iPad next to her displaying the LearnZillion slides, which showed quotes from the text.

One slide had the quote, āThe English were convinced that the rest of the British Empire was backward and uncivilized.ā

āWhat does āuncivilizedā mean?ā Stephenson asked the class. She then had the students turn to their neighbors and discuss why the British thought the American colonists were uncivilized, before coming together as a class to share their thoughts.

The lesson felt organic, Stephenson said later. āItās not, āLetās turn to page so-and-so and do this,āā she said. āYouāre doing all the components you need to do, but everything is not cookie-cutter. It just kind of flows, and you can tell a teacher created that.ā

Bossier Parish has been rolling out guidebooks over the past couple of years and required grades 3-5 to implement at least two guidebooks this school year.

For its 3rd grade, Bellaire Elementary stuck with a textbook from an outside publisher for the first semester and is using two guidebooks during the spring semester: one on Cajun folktales and the other on the Louisiana Purchase. (Starks is teaching her Treasure Island guidebook in addition to the other two, to iron out any last-minute kinks.)

Scores Hold Steady

Between the guidebooks now and the textbook last semester, students are scoring comparably on classroom assessments; but there have been some growing pains with the guidebooks, Principal Alyshia Coulson said.

āGuidebooks were really developed for the higher-achieving child. Thatās another thing the teachers really have to work on: How do you help the struggling student?ā Coulson said.

The state education agencyās Kockler said a teacher team is adding new supports for special education and English-language learners to the guidebooks.

Meanwhile, Bellaire teachers have been using their professional learning community time to dive into guidebooks. Already, Coulson said, they have decided to teach some of the lessons in a different order.

Another challenge is the guidebooks only include three assessmentsāfewer than what the district requires, Coulson said. They include a culminating writing task, one cold-read task, and an āextension taskā that typically involves research. Teachers write their own assessments to fill in the gaps.

āThat was probably the number-one issue that came up with teachers across the state: Where do I get my reading grades? Where do I get my grammar grades?ā Starks said. āItās hard for us as writers to predict what district requirements are. And if we include [extra assessments], they feel like they have to do it.ā āLanguage tasksā to help teachers integrate grammar instruction with the guidebooks will be released in June.

Many of the teachers who wrote the original guidebooks have since left the classroom to become curriculum coaches or work at the state education department, Starks said.

She hasnāt left, she said, ābecause I think that when Iām helping other teachers and when Iām training on guidebooks, ... there is so much value to me being able to say, āIām in the classroom just like you. I am a teacher just like you.āā

Kaufman, the RAND researcher, said having teachers develop curriculum deepens their knowledge and understanding of the standards, which they, in turn, pass on to other teachers.

Indeed, during Louisianaās professional-development sessions on the guidebooks, Starks said teachers appreciated being able to hear practical strategies and tips from the curriculumās authors.

āItās really powerful that it was written by teachers, for teachers,ā Starks said. āIām a 3rd grade teacher in Bossier City, La. I mean, how is it possible that the state saw enough value in me and what I was doing to ask me to do something like this?ā

And her work is spreading beyond the state: Louisianaās guidebooks are open-source, meaning they are freely available online. So far, the department has heard from districts in Connecticut, Florida, Ohio, and Washington state, as well as other organizations that have used the curriculum for training.

In Louisiana, the curriculum has been the hook for the stateās overall focus on improving student achievement, Kockler said. āOur insistence that teachers be a core part of this from the beginning,ā she said, āensured we were building real resources that teachers needed.ā