A new study tracking the classroom impact of the No Child Left Behind Act in California, Georgia, and Pennsylvania suggests that teachers are adjusting their teaching practices in response to the law—but not always in ways that educators and policymakers might want.

According to , majorities of elementary and middle school science and math teachers in all three states report in surveys that they are making positive changes in the classroom by focusing on their states’ academic standards or searching for better teaching methods.

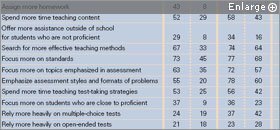

At the same time, though, sizable percentages of educators are also spending more time teaching test-taking strategies, focusing more narrowly on the topics covered on state tests, and tailoring teaching to the “bubble kids”—the students who fall just below the proficiency cutoffs on state tests.

“This is telling us we’re seeing both positive responses as well as responses that raise some concerns,” said Laura S. Hamilton, the study’s lead author and a senior behavioral scientist at RAND. Her study was among five reports spotlighted here this week at a conference organized by the prominent think tank.

With financing from the , Ms. Hamilton and her research partners have been surveying teachers, principals, and superintendents in the three study states since 2002, the year the NCLB legislation became law, as well as conducting more in-depth studies in 18 districts spread across those states.

Learning and Morale

This week, she presented findings from surveys conducted over the 2005-06 school year, the third and final year of the study. A written report detailing results from the first two years of the study was also posted on RAND’s Web site for the first time this week.

The findings suggest that educators on the ground are viewing and responding to the federal law in complicated ways. For instance, across all three states, two-thirds or more of superintendents and principals and 40 percent to 60 percent of teachers said that staff focus on student learning had improved as a result of the new accountability pressures, but many also agreed that staff morale had declined.

Elementary school teachers reported that their instruction differed as a result of math and science assessments.

Note: Response options included not at all, a small amount, a moderate amount, and a great deal. Shown are percentages reporting that they engage in each practice a moderate amount or a great deal as a result of the state tests. The questions were not presented to Pennsylvania science teachers because Pennsylvania did not have a statewide science test.

SOURCE: RAND Corp.

Teachers were more likely than the administrators, though, to pick up on problems or negative consequences with the testing-and-accountability systems in their states, such as a concern that state tests were misaligned with the curriculum. In middle school science, for example, the percentages of teachers reporting that kind of mismatch in the 2004-05 survey ranged from 63 percent in Georgia to 74 percent in California.

Also, while most teachers and administrators agreed that learning opportunities for struggling students had improved as a result of the law, half or more of teachers across the three states and all levels of schooling worried that high-achieving students were not receiving “appropriately challenging curriculum or instruction.”

“These are just teachers’ opinions, but we need to take them seriously because teachers’ support is important in making successful policy changes,” Ms. Hamilton said.

Demographic Diversity

While California, Georgia, and Pennsylvania were chosen for the study because they represented different demographic makeups and were at different stages in developing what the report calls “standards-based accountability systems,” the patterns of classroom effects were similar in all three states, according to the study author.

The other reports highlighted at found that states and districts across the country were using similar strategies to respond to the federal law.

Three reports, for instance, noted that use of data-driven efforts to improve schools was becoming widespread. Two-thirds of schools, for example, have implemented periodic “progress” tests to monitor student achievement throughout the year and identify instructional gaps, said Brian M. Stecher, a senior social scientist at RAND. He is one of the researchers taking part in a federally funded national evaluation of the NCLB law, which has not yet been released.

Studies also converged in finding widespread sentiment among educators for using accountability measures that gauge progress by the academic growth that students make, rather than by counting the percentages of students that reach state proficiency targets. Ms. Hamilton said teachers suggested such growth-model systems, besides giving them more credit for their hard work, might take the undue focus off the “bubble kids” in their classrooms.