Corrected: An earlier version of this story incorrectly spelled the name of Socastee High School.

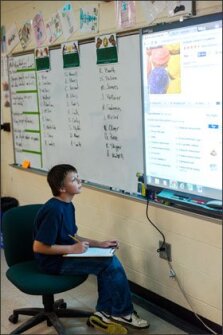

As students file into math teacher John Williams’ 6th grade class at Whittemore Park Middle School here, they eye the back wall carefully. That’s because their names are displayed there, for all to see, along with what percentage of coursework they’ve completed. No grades are posted, but each day students can watch their progress toward curriculum completion.

The idea for the wall, a similar version of which appears in most classes at Whittemore Park, arose during the past school year as the low-income school put in place a personalized, blended learning program. As part of the effort, students often work independently on school-issued iPads or MacBooks, using interactive curriculum tailored to their learning needs. But teachers soon discovered that students were slacking off when they were working on their own, so they came up with the idea of publicly showing individual progress.

The idea was controversial, said Jennifer M. Howard, a 6th grade English/language arts teacher, but teachers found it helped hold students accountable. “The kids are really motivated by tracking their progress,” Ms. Howard said. “Even if they’re not motivated by grades, they are interested in how they’re doing in comparison to their peers.”

In Mr. Williams’ mathematics class in late September, the wall showed many students’ names hovering in the 10 percent- and 20 percent-completed categories, which is normal for the beginning of the school year. But two students had already finished 75 percent of the 6th grade math curriculum, something the teacher said would have been impossible without the differentiated instruction provided by the math software.

The schoolwide personalized learning effort has transformed instruction at , boosting test scores, student engagement, and teacher attendance. Now, much of the 42,000-student is attempting to follow suit through the district’s Personalized Digital Learning initiative, though without some of the supports that Whittemore Park has enjoyed.

Funded in part by a local sales tax, this new educational model will expand to include nearly all grades in the Horry district over a three-year period. It began districtwide in August 2013, when teachers in the rest of the county’s 10 middle schools received their iPads and students got them in January. This school year, the district’s 14 high schools and secondary schools programs are rolling out their own versions, providing each student with a $600 Dell Venue tablet, which they can take home. After that, an elementary-grades team will select a device, and teachers and students will receive them.

Horry officials know the change is significant for students and teachers, and they say it won’t be a surprise if they see an innovation dip—a drop in student performance as the district adjusts to a new way of operating.

“We know we’re going to keep having issues and we’re going to fix them as we go along,” said Edi R. Cox, the district’s executive director of online learning and instructional technology. “We might have an innovation dip, but that’s OK. We’re doing the right thing for kids.”

Turning Around a School

The Horry district includes Myrtle Beach and its central tourist area, where visitors can see shiny attractions like the Elvis and Dolly Parton impersonators at Legends Music Hall, the memorabilia-filled dining room of the Hard Rock Café, or the shark tank at Ripley’s Aquarium. Whittemore Park, with 85 percent of its students from low-income families, isn’t far from the restaurants, hotels, and attractions that employ many students’ parents.

The districtwide personalized learning initiative has its origins at Whittemore Park, where dismal test scores earned the school a D grade from the state for the 2011-12 school year. Horry district officials ordered an overhaul, bringing in a new principal, Judy Beard, who had school turnaround experience.

When Whittemore Park won a grant for $150,000 in 2012, the school bought iPads, adding to the MacBooks that Ms. Beard had purchased with federal Title I funding, and the school upgraded its technology infrastructure and invested heavily in professional development.

A 6th grade English/language arts classroom is a good example of how the personalized learning program works. On a rainy September afternoon, students discussed whether schools should monitor students’ social-media activities. Along the sides of the room, students on MacBooks used the Achieve 3000 differentiated-instruction curriculum to read an article on the topic. All students read the same piece, but the software tailored every article to each student’s individual reading level, set after an assessment by the program, but which can be changed by the teacher. In the middle of the room, some students used iPads to watch a related CNN video or to respond to open-ended questions on the topic.

A data dashboard, created by , a Palo Alto, Calif.-based for-profit company that provides blended learning services and which has guided Whittemore Park and the district, provides teachers with a comprehensive look at student achievement and progress through the curriculum. It can organize and analyze the data in a variety of ways, even by specific academic standard.

Similarly, in Mr. Williams’ math class, students often work independently on MacBooks using adaptive curriculum provided by ALEKS—Assessment and Learning in Knowledge Spaces—a McGraw-Hill Education product.

Sixth grader Christian Wood said he likes the program because he’s good at math and can move ahead if he wants to. Each student’s math-data dashboard displays a pie chart of the category of lessons done and still to do. 69��ý may choose the category of lessons to work on and when.

On a Monday, Christian had already completed three of four math lessons on a particular topic required that week. He said the technology helped him improve his grades. “I’m not good with organization, and this automatically turns in our work,” he said.

The school also uses a block schedule, with 100-minute classes, and a rotational model. In Mr. Williams’ class, after 25 minutes, a cellphone alarm rang, and organized chaos ensued: 69��ý at the middle tables moved to seats along the wall with the MacBooks. 69��ý working there moved to the middle, in front of the interactive whiteboard with Mr. Williams. Still another group left the room to work with a math teacher down the hall.

There were glitches. Mr. Williams, for example, realized too many students were in his room, so some had forgotten to rotate out. But the transitions were mostly smooth, and nearly all the students stayed on task.

The Good and the Bad

Though Whittemore Park has seen progress, it’s also had more financial assistance than other schools in the district are likely to receive. The initial $150,000 Next Generation Learning Challenges grant and an additional $50,000, plus collaboration with and support from other school district grantees, have been critical, Principal Beard said.

During the 2013-14 school year, Whittemore Park Middle School implemented its personalized, blended learning program. The initiative started by providing 6th grade students with iPads at the beginning of the school year. Midway through the year, 7th and 8th grade students received their iPads.

SOURCE: Education Elements and the Horry County School District

Education Elements created several tools for the school—like a single sign on for access across educational programs and a data dashboard—that are not available at the high school level. And Whittemore is also working with several other organizations, including the Portland, Maine-based Quaglia Institute for Student Aspirations, on issues related to school culture. Most other schools in the district do not have those partnerships.

Cross the Waccamaw River and head southeast toward the beach to the Horry district’s 1,600-student , and visitors can watch the newest version of the personalized learning initiative unfold. At the end of September, school officials had just issued Dell Venue tablets to the majority of students, though some still didn’t have them, either because parents didn’t want the financial responsibility for loss or breakage or because of impediments like student absences.

Teachers, who received the devices in April, were still working to integrate them into lessons. Some were using them throughout each class period, others only sporadically. Twenty-five percent of teachers had been tapped as “superusers” and mentors for the rest of the staff.

Biology teacher Diane Goshert is one of those high fliers. Along with the science equipment, snakes, tarantula, and family of crested geckos in her classroom, she has a cart filled with iPads previously purchased with grant money. Last month, students used the iPads and their tablets, sometimes simultaneously, to watch video tutorials, complete lab simulations, and rewrite class notes.

Ms. Goshert allows students to choose how they learn the material, and the technology provides the options. “Everybody doesn’t learn the same way,” she said.

Watch science video created by Whittemore Park Middle School students:

Teachers who are newer to the effort say they’ve been working longer hours and had to overcome anxiety about the technology. Google Classroom, a new organizational tool being used at Socastee, was just released in August, and teachers had to scramble to master it before students got their tablets.

“I am not resisting, but it is difficult to learn and understand the technology and the technicalities,” said global-studies teacher Marty Jacobs, though his colleagues said he has actually embraced the initiative.

Other teachers say the technology saves time. Socastee English/language arts teacher Suzanne Troiani, who has a technology background, said programs like Flubaroo do automatic grading, and ExitTicket lets teachers provide quick assessments. “They can take a quiz in the beginning of the block [class], and it can be graded by the end,” Ms. Troiani said. That information can inform her instruction almost immediately. “I feel I can be more effective commenting and working electronically.”

But it hasn’t been all smooth sailing. Some parents protested the optional $50 insurance fee. 69��ý had to be rewired for Wi-Fi access, and at first, the network was overloaded. For Socastee and the rest of the high schools, unlike the middle schools, there is no overall data dashboard to inform students and teachers and no single sign on to access the various subject-based software programs, a nuisance which several students complained about. The school has set up a help desk staffed mostly by students to make minor tablet repairs and help both fellow students and teachers with issues, and the office is busy with those seeking assistance.

In math teacher Jimmy Bailey’s Algebra 1 class, he used the tablet to see how many students were answering problems correctly during a 10-question exercise.

But 9th grader Kacy Ervin didn’t have a device and hunched over the cracked screen of her smartphone trying to access the material. Eventually, she moved to a desktop computer in the back of the room. 69��ý can use their own devices, and the school disassembled its computer labs and scattered desktops throughout the classrooms as a backup.

Mr. Bailey, who is still learning how to use the devices effectively in his classroom, said Google Classroom alerted him that the day before, when a substitute was leading the class, only five students submitted their notes as assigned. But when he tried to use ExitTicket to assess students, the software wasn’t able to properly grade questions with explanatory, sentence-style answers.

“The program is going to tell you you’re wrong, no matter what you write,” said Mr. Bailey, as he tried to reassure students. “The downfall of this is that it tries to grade everything.”

Preparing Teachers First

Whittemore Park itself has worked through plenty of kinks. The school uses educational resources from ALEKS, Achieve 3000, Discovery Education, and Compass Odyssey. But when the Whittemore Park initiative launched, there was no single sign on, as there is now for middle schools.

“We were losing so much instructional time,” Principal Beard said.

Chat: Putting Personalized Learning to Work

Monday, Nov. 10, 2014, 1 to 2 p.m. ET

Educators from South Carolina’s Horry County School District will discuss the ins and outs of putting in place effective personalized learning initiatives in middle schools and high schools.

• Sign up now.

In addition, with a heavy emphasis on English/language arts and math and the 100-minute block schedule, something had to give. So students get science and social studies every other day, and the curriculum for those two subjects they’re using is not inherently adaptive. Science and social studies teachers in those subjects have had to collect and piece together their own versions of adaptive lessons.

Another problem was the infrastructure of the decades-old building. When the personalized learning initiative launched, the Wi-Fi signal wasn’t strong enough to penetrate walls, and the broadband would often get overloaded.

“Any time there was a problem, the children would get off task, which means behavior issues,” Ms. Beard said. “Then the teachers would throw up their hands and say they wanted to go back to the way it used to be.”

But a strategic move nearly everyone agrees the district has done right is its investment in professional development. Teachers at Whittemore were given their devices nearly a year before students were to give them time to prepare. Not wanting to schedule professional development after school hours when teachers were likely to be tired, educators at Whittemore instead give up two of their 50-minute planning periods per week for professional development related to the personalization initiative, Ms. Beard said. It’s a move that might not work in a unionized district, she acknowledged, where that would have to be negotiated through a union contract. But it worked here.

That emphasis on professional development is echoed across the district. Teachers at the other middle and high schools also were given devices months before students, and they receive weekly professional-development sessions. The district hired six new digital integration specialists just for the Personalized Digital Learning project. Numerous content-area specialists also provide regular support.

“What has been a huge benefit is getting those devices in the hands of the teachers prior to issuing them to students and doing a lot of heavy professional development before teachers felt the stress of the kids having the devices in the classrooms,” said Ms. Cox.

Mr. Williams, who has taught at Whittemore Park for 15 years, said the blended learning effort has been a significant commitment for teachers, but one that has excited them.

Over the years, “I lost my drive and passion,” he said. “I’m so glad to be here now. I really feel I’m meeting the needs of the kids.”