—Bryan Toy

For many years, I have been a skeptic about putting computers in classrooms to transform teaching and learning. Sure, I got called lots of names from champions of desktops and vendors—“Luddite” being the more printable one—but I always considered the source. My reasons for being dubious were simple: No evidence was available for improved learning, better teaching, and students’ getting high-salaried jobs after graduation to justify large expenditures to wire buildings, buy hardware, and crow about high-tech schooling. But in the past few years, much of the name-calling has faded.

Now, conversations about computers in schools have become less testy than exchanges I had a decade ago. As fiscal retrenchment has reduced school budgets, there is far more willingness on the part of ardent promoters to consider answering tough questions: Why don’t teachers integrate the new technologies into their daily instruction? How much of the technology budget is devoted to on-site professional development and technical support of teachers? Why is it so hard to show that teachers’ use of classroom technologies has caused gains in academic achievement? That these questions could be asked now and thoughtfully considered is encouraging.

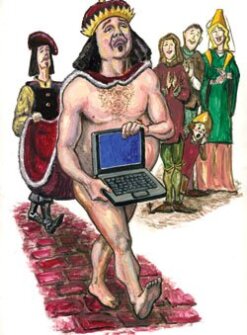

Except when it comes to one-to-one computing and the spread of laptops nationwide. In this area, I hear again the outlandish claims of technology champions that giving each student a laptop will revolutionize teaching and learning—and, yes, increase test scores to boot.

The argument for each student’s having a laptop goes something like this: Every student has a textbook, pen, and paper; therefore, every student should also have a computer. Computers are tools of the trade, so to speak. In what business, hospital, or police precinct, advocates ask, would four or five employees, doctors, or officers have to compete for one computer? None. Even when we turn in our rental cars, they argue, the person in charge has a hand-held computer. If America wants productive future employees, give every student a laptop to use in school.

With many districts already having one-to-one access, what has happened in classrooms? Journalistic accounts and surveys of 1:1 programs in Maine; Henrico County, Va.; Fullerton, Calif.; and individual districts scattered across the country report extraordinary enthusiasm. Teachers tell of higher motivation from previously lackluster students, and more engagement in lessons. 69´«Ă˝ and parents describe similar high levels of use and interest in learning.

Yet much of this is drawn largely from teacher and student self-reports. Without researchers’ direct observation of classroom lessons for sustained periods of time to confirm these self-reports, doubts about teacher claims of daily use and students’ long-term engagement are in order. A few researchers have done this. Consider, for example, the work of Judith Sandholtz and her colleagues on the Apple Classrooms of Tomorrow, or ACOT, program between 1985 and 1998.

The original ACOT project distributed two desktop computers (one for home and one for school) to every student and teacher in five elementary and secondary classrooms across the country, eventually expanding to other classrooms and schools. ACOT researchers reported positively about student engagement, collaboration, and independent work, much as 1:1 researchers do today.

But they also found that for teachers to use computers as learning tools, a 1:1 ratio was unnecessary. In elementary and secondary classrooms, a half-dozen computers could achieve the same level of weekly use and maintain the other tasks that teachers and students had to accomplish. Few people, however, have ever heard of the ACOT experiment.

Even if champions of laptops had heard of ACOT and found the positive results convincing, those who pay for public schools want more than the tap-tap-tap of keys in classrooms. Policymakers, parents, and taxpayers expect teachers to make children literate and numerate while also promoting moral behavior, civic engagement, and a better society. They expect teachers to maintain order in their classrooms, make sure students are respectful and dutifully complete their work, and ensure that those in their charge achieve curriculum standards as measured by tests. Abundant access to new technologies is almost beside the point. Except for achievement.

The fact is that one-to-one access has failed to show a direct link to improved test scores. For the past 80 years of research on technology’s impact on learning, from primitive projectors to modern laptops, not much reliable evidence has emerged to give impartial observers confidence that students’ use of computers or any other electronic device leads directly to improved academic achievement.

What causes enthusiasts to attribute gains in achievement to laptops? Again and again, officials mistake the medium of instruction—laptops—for how teachers teach. Smart people have said for decades that personal computers, laptops, and hand-held devices are only vehicles for transporting instructional methods; machines are not what teachers do in classrooms. Teachers ask questions, give examples, lecture, guide discussion, drill, use small groups, individualize instruction, organize project-based learning, and craft blends of these teaching practices.

Officials mistake the medium of instruction for how teachers teach. Personal computers ... are only vehicles for transporting instructional methods; machines are not what teachers do in classrooms.

The University of Southern California psychologist Richard E. Clark put it succinctly: Media like television, film, and computers “deliver instruction but do not influence student achievement any more than the truck that delivers our groceries causes changes in our nutrition.” Alan Kay, who invented the prototype for a laptop in 1968, made a similar point when he said that schools confuse the music with the instrument. “You can put a piano in every classroom, but that won’t give you a developed music culture, because the music culture is embodied in people.” The music is in the teacher, not the piano.

But school boards eager to show laptops boosting achievement forget the distinction. The typical study of 1:1 laptop programs compares the test scores of students in classrooms with laptops to those of students in other classrooms without them. Yet these studies seldom use the same teacher for both the laptop and nonlaptop classes. Nor do they ever isolate and examine how teachers teach during the time of the study. These researchers have confused the piano with the music teacher. So when initial gains in test scores occur, they are attributed to laptops, not to what and how the teacher teaches.

One-to-one laptop programs are popular. Districts compete to become the first in their area to achieve the ratio. Yet the hype shrouds easily available facts about teaching, learning, and what schools are expected to do. Not to be skeptical at moments like this invites brain death.