Leonard Yavny believes Darwin’s theory of evolution contradicts biblical truths. He also thinks youths shouldn’t be taught about sex; if they learn about it, they might try it, he reasons. He requires his own children to be chaperoned on dates until they are married. And he doesn’t want his children to be exposed to Halloween, which he believes is a holiday originating from the devil.

Yavny, the 42-year-old father of five children between the ages of 10 and 19, finds that these particular beliefs conflict with those of many of the teachers or students at the public schools his children attend here. But he has never complained to school personnel.

Instead, he counteracts what his children face at school by pointing out to them what he believes to be false teaching, holding them to specific expectations, and occasionally pulling them out of school activities.

Last Halloween, for example, he and his wife, Galina, kept their children home from school.

|

|

Yavny is a conservative Christian and an immigrant from Ukraine who shares with many immigrants a critical view of the prevailing attitudes and beliefs that his children encounter in school.

Having received the largest number of immigrants ever in a single decade during the 1990s, the United States has become home to an increasing number of parents such as Yavny whose traditional values don’t mesh well with the more liberal values that tend to permeate public schools.

Harrisonburg, a city of 42,000 set in a farming region of Virginia, has received an immigrant wave of its own as jobs in the poultry industry have drawn newcomers here. In five years, the population of language-minority children in the Harrisonburg schools has swelled from about 400 students, most of whom spoke Spanish, to 1,180 students who speak 39 different languages.

And so, it’s not hard to find immigrant parents here who share Yavny’s perspective. They resist assimilation and expect their children to follow their lead. “We are raising our kids in the United States,” says Benita Castro, a native of Mexico who along with her husband recently threw an elaborate church ceremony and reception, or ��ܾ��Գ���ñ�����, to celebrate her daughter Nancy’s 15th birthday, “but we’ll stick to our morals.”

Aisha Rostem, a Kurdish Muslim who sends her two teenage daughters to schools here, says through an interpreter, “I’m praying that they will be safe—that they don’t fight, that they don’t get involved in bad things.”

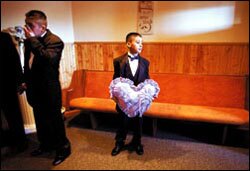

|

Jose Fereteiz, 13, center, stands in the lobby of Torre Fuerte Pentecostal Church in Harrisonburg, Va. He is clutching a pillow that will hold a crown for his cousin, Nancy Castro, who is being honored with a ��ܾ��Գ���ñ�����, or 15th- birthday celebration. —Photograph by Allison Shelley/Education Week |

How these parents help their children make sense of the two worlds they live in—the world of school and the more traditional world of home and community—can have a huge effect on their children’s academic success and school life. So also can schools’ handling of this cultural clash make a difference in immigrant children’s lives.

While in the past sociologists tended to conclude that immigrant children who assimilated into American culture the fastest were the most successful academically, in recent years some researchers have challenged that conclusion.

A longitudinal study of some 5,200 youths who are children of immigrants or who immigrated to the United States by the age of 12 shows, for example, that children who learn English but also hang on to their first language and their families’ traditions and values are less likely to fall in with the wrong crowd and be distracted from their studies.

“Those who feel a strong attachment to their parents, who feel guilty because of their parents’ sacrifice—those are the ones you find working much harder than any of the native kids,” says Rubén G. Rumbaut, a sociologist at the University of California, Irvine, who conducted the study with Alejandro Portes.

With Americanization, Rumbaut points out, “self-esteem goes up, English-language ability goes up. [But] the amount of time spent on homework goes down and so does the GPA.”

Yavny and his wife and their four children arrived in this small city in the Shenandoah Valley 11 years ago as refugees. Their youngest child, now in 5th grade, was born in the United States.

Leonard Yavny tells stories about how he and his family strove to practice their Pentecostal Christian faith despite persecution in the days of the Soviet Union. He relays how his father spent the 1970s in a Siberian prison for preaching his faith, and how he himself experienced educational and job discrimination because of his religious beliefs. Because he wasn’t a member of the Communist youth league, he couldn’t enroll in a university, so he became a truck driver and then a carpenter. Here in Harrisonburg, he owns and operates a used-car dealership with his twin brother.

In the United States, the Yavnys strive to keep their faith despite the influence of more secular American values.

|

|

In the Soviet era, Pentecostals lost their lives because of persecution, but in the United States, “they are losing their children another way,” says Viktor Sokolyuk, a Ukrainian Pentecostal who, along with the Yavnys, attends Harrisonburg’s Slavic Christian Church. “The Christian society is more liberal,” he says. “It’s not only the school society. ... Here freedom has destroyed us.”

Harrisonburg isn’t exactly a wild and crazy place. It has long been settled by Mennonites and Brethren, who tend to fall on the conservative end of the spectrum of Christian denominations in the United States. Traditional immigrant groups have gravitated toward the area partly because of the conservative lifestyles of the Americans families who settled here.

Nearly one in three students in the 4,000-student district here now speaks a language other than English at home.

By most accounts, the Harrisonburg school system has adjusted remarkably well to its new makeup of students. It quickly expanded programs to teach students English as a second language, for instance. It organized a system for volunteers to serve as interpreters for mothers and fathers during parent-teacher conferences.

|

Yelena Yavny, second from right, is the only girl in the 8th grade to regularly wear skirts, rather than pants, to classes at Thomas Harrison Middle School. —Photograph by Allison Shelley/Education Week |

But the district is still in the throes of figuring out how best to work with immigrant parents. To that end, it hired for the first time this school year someone whose job is to communicate with such parents and increase their involvement in school. Her name is Tonya Osinkosky-Perez, and she’s fluent in Spanish. She splits her time between the district’s only middle school, Thomas Harrison, and its only high school, Harrisonburg High.

She uses the Spanish word choque, or collision, to describe the clash between values of many immigrant families and those of mainstream America.

Exacerbating the clash are changes that occur in many families as they adjust to their new world. The balance of power between men and women often changes when women who didn’t work in their home countries take jobs in the United States. Children gain a position of power in their new homes that they did not have in their native countries if they learn English faster than their parents do.

Harrisonburg administrators deal with some aspects of the culture clashes directly. For example, they let immigrant parents know through a letter, translated into their native language, that their children can opt out of “family life” classes, or sex education. They permit girls from cultures that require modest dress to wear sweat pants instead of shorts for gym class. And during Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting, they provide separate rooms for boys and girls to pray at the high school.

But it’s difficult for school employees to address one concern that arises often among immigrant parents, says Osinkosky-Perez. The worry is that by emphasizing independence, Americans permit children to be disrespectful to adults.

The Ukrainian Pentecostals in Harrisonburg, who worship with Pentecostals from other parts of the former Soviet Union, would like to lessen some of the cultural conflict they face with public schools by sending their children to private Christian schools.

At a gathering of parents at the Slavic Christian Church, Pavel Yavny, the pastor of the church and an older brother of Leonard Yavny, wondered aloud if the U.S. government had any money available to support Ukrainian and Russian children to attend local Mennonite schools.

Most of the Ukrainians and Russians in Harrisonburg are too poor to send their children to private schools.

|

|

In some communities, though, immigrants have garnered the resources to start private schools.

A Russian church in Utica, N.Y., opened a private school several years ago to serve an emerging community of some 2,500 Ukrainian and Russian Pentecostals.

“Parents wanted their children to get more education and to teach them how to behave themselves, because the public school isn’t as strict as it is supposed to be,” says Pavel Brutsky, a Russian Pentecostal and a case manager for the Refugee Center in Utica. “The children in the [public] high school behave bad. Even in the middle school, [students] use a lot of profanity. We cannot tolerate it.”

Muslim immigrants continue to start private schools across the country, in part to distance their children from what they view as negative influences in American culture.

The desire of immigrant groups to start their own schools to preserve their traditions and culture is as old as the nation, according to Charles L. Glenn, an education historian at Boston University.

|

Members of the Slavic Christian Church’s youth group sing hymns in Russian during a Saturday-evening service —Photograph by Allison Shelley/Education Week |

But Glenn believes the anxiety among immigrant parents about what their children may pick up at school has grown more intense, as traditional structures in American society increasingly have broken down, and urban schools and the neighborhoods around them have become unsafe.

“There’s a tremendous fear [among immigrant parents] that kids will be sucked down by what they see as a tremendously destructive culture,” Glenn says, pointing out that immigrant parents view the sexual permissiveness and consumerism of American society as toxic.

Leonard Yavny, whose Russian name is Leonid, says that his family’s participation in the Slavic church has aided him and his wife in passing on their traditional ways to their children. The church’s youth group helps keep his children interested in Christianity, traditional values, and the Ukrainian and Russian languages.

All five Yavny children have learned at least the rudiments of how to read and write Russian, though they aren’t literate in Ukrainian. The two youngest children spend two hours a week in a Russian-language school, started by the church four years ago. Yavny can get his ideas across in English, and his wife also speaks some English, but the family speaks Ukrainian at home.

|

|

Two Yavny children have graduated from high school. One now works with his father selling cars. A sister is studying accounting at a local community college.

Yelena Yavny, who is 14 and in 8th grade at Thomas Harrison Middle School, says her social life is grounded in church rather than school. When asked if she ever attends school activities outside of class, she says, “Usually I don’t have time, because we have church.”

Besides going to church on Sunday morning, her family attends evening services five nights a week. Rather than dreaming about trying out for a school play or playing a sport at school, Yelena looks forward to the day when she’ll join her church’s youth group.

When asked how her world at home differs from her world at school, Yelena brings up the issue of dress. She’s the only girl in her grade who wears skirts to school instead of pants.

“Mainly, it’s better if I wear a skirt,” she says. “My dad prefers I wear a skirt. It’s my religion. I know I’m doing right. If people say something, it doesn’t bother me anymore.”

Her father says he tells Yelena, “Please go to school [dressed] like you go to church because the Bible says, ‘Be salt and be light for the other people.’ Be a leader.”

Yelena also mentions that people of her church don’t say the Pledge of Allegiance, so she stands quietly when her classmates say it.

Yelena is a strong student who, having lived in the United States since she was a toddler, never attended schools in Ukraine. She gets mostly A’s on her report card.

A slender girl with fine features, she is quiet and rarely volunteers to speak in her classes, though her spoken English is flawless. During a recent social studies class, when students get into groups to review for a test, many students talk loudly or tell jokes. Yelena works quietly and quickly with three other students to complete the assignment.

For Yelena’s 16-year-old brother, Slavik, a 10th grader at Harrisonburg High, church rather than school provides a social life as well. He doesn’t go to school football games or dances. His peers at school, he says, “party,” which he doesn’t do.

Similarly, Hispanic Pentecostal and Kurdish Muslim families have created a setting here that provides both social activities and teachings about their religion and culture—and an alternative to school activities.

Harrisonburg High 11th grader Benita Castro, for example, attends the New Life Church, where her father is the pastor and services are conducted in Spanish, four nights a week. The 16-year-old, who has the same name as her mother, dates a boy who attends her church. At school, she tends to hang out with other young people who go to her church.

Benita spent much of a recent Saturday with her family and church attending the ��ܾ��Գ���ñ����� of her sister Nancy. It is a traditional Mexican birthday party marking a girl’s budding womanhood and signaling her availability for dates. Benita, who was born in Texas, had a ��ܾ��Գ���ñ����� herself and believes that such events are important for carrying on her family’s Mexican culture.

But she differs with some of the expectations of her parents, such as their rule, which her mother says she’s broken, that all her dates be chaperoned. Still, she was grateful that her parents permitted her to start wearing pants, instead of skirts, to school this year for the first time. “I don’t feel so much like an outsider,” Benita says. “Other students don’t look at me when it’s cold and say, ‘Are you crazy?’ ”

She says it’s sometimes hard to live in two cultures—that of school and of home. For example, in biology class last year, she felt torn between the views of her teacher and those of her mother over how human beings came into existence. Her mother fretted that her teacher had taught her the theory of evolution.

Benita says she persuaded her mother not to complain to the school. “I didn’t want to be embarrassed,” she says. Her mother says she and her husband have decided to deal with such issues at home by explaining to their children what the Bible says and what they believe.

But Benita, who visits Mexico every summer, adds that her parents’ emphasis on tradition helps her do well academically. “They have high expectations for me,” she says. She takes a full load of college-prep courses.

|

Nancy Castro, Benita’s sister, celebrates her 15th birthday with almost as much fanfare as a wedding —Photograph by Allison Shelley/Education Week |

Thanks to the construction of a mosque here several years ago, Bayan Rostem, an 8th grader at Thomas Harrison Middle School, has a community setting where she can learn about her family’s religion and traditions. The 14-year-old immigrated to the United States from the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq as a refugee seven years ago. Her family lived for more than a year in Chicago and then moved here to Harrisonburg.

On the day of her return to school in December after celebrating Eid, the holiday marking the end of Ramadan, Bayan’s face lights up when she talks about the events.

“You wake up early, go to the mosque, pray,” she says. “After the mosque, there’s lots of food. You give people a hug and say ‘thanks.’ You go home and eat. Your dad gives you money. You go shopping.”

On her first day back to school after Eid, she wears new clothes she bought with her gift money—a blue hooded sweatshirt and black sparkly turtleneck.

But when Bayan meets with her non-Kurdish friends over lunch the first day back at school after celebrating Eid, she doesn’t tell them about what she did on the holiday. Instead she quizzes them about school assignments. On her last report card, she got A’s, B’s, and C’s. Bayan, who is the only Kurdish girl in the 8th grade, has made friends with a group of girls who include African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, and a Caucasian.

However, some immigrant students have difficulty negotiating the two different worlds of home and school, says Osinkosky-Perez, the liaison to immigrant parents for the middle and high schools.

For example, some Latino youths react by refusing to speak Spanish with their parents, she says. A Muslim student from Bosnia upset her parents by wanting to date a Christian boy whom she’d met at school, she relays.

Irene Reynolds, the principal of Harrisonburg High School, observes that no matter how traditional the family, youths tend to respond to peer pressure.

Immigrant students soon catch on to fashion trends and challenge their families’ cultural codes to wear the new styles, Reynolds says. A Muslim girl, for example, may continue to cover her head and wear long- sleeved blouses, but she’ll also wear a tank top under her blouse.

“They definitely live two lives,” the principal says. “After they are here for a very short time, most turn into typical [American] teenagers. [But] when they go home, it’s a different culture.”