Many of the teenagers who enter juvenile-justice systems with anger problems, learning disabilities, and academic challenges receive little or no special help for those issues, and consequently fall further behind in school, a report released Thursday concludes.

“Way too many kids enter juvenile-justice systems, they don’t do particularly well from an education standpoint while they’re there, and way too few kids make successful transitions out,” said Kent McGuire, the president and CEO of the Atlanta-based , which produced the report, “”

The report characterizes the problems plaguing juvenile-justice systems as “systemic.” It found a lack of timely, accurate assessments of the needs of students entering the system, little coordination between learning and teaching during a student’s stay, and inconsistency in curricula. Many of the teaching methods were also inappropriate, outdated, or inadequate, and little or no educational technology was used.

“We need to help find ways to create structures and dramatically change how schools and principals and teachers [in juvenile-justice systems] are held accountable,” said David Domenici, the executive director of the Center for Educational Excellence in Alternative Settings, in Washington.

“We have kids who have not done well in school, but, more or less, they have to come every day. They’re a captive audience,” he said. “We can transform their perspective on school. But the reality is, education has been forgotten [in juvenile-justice systems].”

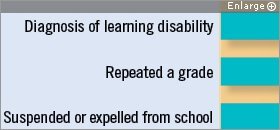

Youths in the juvenile justice system have many difficulties related to education.

SOURCE: U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

On any given day, 70,000 students are in custody in juvenile-justice systems across the country. Nearly two-thirds of those young people are either African-American or Hispanic, and an even higher percentage are male. Those systems, though, may be doing more educational harm than good, according to the report.

Once in the programs, the report says, students made very little academic progress—a situation particularly taxing to students in such facilities for longer periods of time. Fewer than half of “longer term” high school students (those enrolled for at least 90 days) earned one or more course credits while attending juvenile-justice schools. Only about 25 percent of those students were on track to re-enter public schools.

According to federal reports mentioned in the study, only 15 percent of all students in juvenile-justice facilities, and 26 percent of longer-term students, improved to some extent in reading during their custody. In the Southern states, that proportion was 9 percent.

And just 9 percent of students ages 16 to 21 in such facilities were on track to earn a GED credential or high school diploma. Two percent were accepted and enrolled at a two- or four-year college.

Nearly a third of the individuals in juvenile-justice facilities who were tested were diagnosed with learning disabilities, though fewer than 25 percent received special education services and supports to address those disabilities, according to the report.

Racial Disparities

The report also notes that a disproportionate number of the students are male and members of minority groups. In 2010, two-thirds of the young people in custody in the United States were youths of color: 41 percent African-American and 22 percent Hispanic. Eighty-seven percent were male.

The racial and ethnic disparities were even starker in the South, which had a higher percentage of African-American and Hispanic youths than the country as a whole. Of all African-American youths housed in juvenile-justice facilities in the country, 41 percent were located in 15 Southern states. Twenty-one percent of all Hispanic youths housed in juvenile-justice systems in the country were in the South.

The report notes that students who had been suspended or expelled from school were more likely to enter a juvenile-justice program.

Federal data on student suspensions and expulsions show minority students are also disproportionately suspended and expelled from public schools.

Adding to the grimness of the picture for juvenile offenders, some studies, cited in the report, show that as many as 70 percent to 80 percent of all individuals who are released from residential juvenile-justice facilities will return to jail after two to three years.

“The better we could get at keeping kids in school in the first place, at bringing down suspension rates and improving discipline policies and practices,” said Mr. McGuire, “the more likely kids will be to complete their high school degrees and find opportunities in postsecondary education, and the less likely it is that they will land in the criminal-justice system in the first place.”

Cost Comparisons

Juvenile-justice systems are more expensive than keeping teenagers in school.

For example, in Georgia, a special commission on juvenile-justice reform estimated that the cost of each placement in a state facility averaged from $88,000 to $91,000 per year. The annual average cost in Louisiana was $119,073, according to a 2009 audit report. In Virginia, it was an estimated at $101,037 annually, and in Tennessee, the average cost was $92,060, according to data from the states.

But the costs, both fiscal and societal, are more than those numbers suggest, argues the Southern Education Foundation report. Those numbers usually do not include costs for local police, social service agencies, juvenile-court judges and court personnel, public defenders’ offices, and support personnel who are involved through the arrest, referral, intake, screening, and evaluation processes.

“These are still kids,” said Mr. McGuire. “Education needs to become a much bigger focus in these detention centers, because that’s the pathway to participation in the economy and society. It costs way too much for us to not figure out how to do that.”