Includes updates and/or revisions.

The federal government has taken control of state education systems, and state leaders want them back, legislators around the country say.

Through the No Child Left Behind Act, Congress and the U.S. Department of Education have forced state lawmakers to expand their testing systems, alter the ways they reward and punish schools, and spend their states’ own money on federal mandates, the National Conference of State Legislatures contends in a report issued Wednesday.

To address the situation, the 76-page report says, Washington should give states broader authority to define student-achievement goals and more latitude to devise the strategies to help students reach those goals.

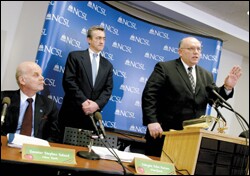

“States that were once pioneers are now captives of a one-size-fits-all accountability system,” New York state Sen. Steve Saland, the Republican co-chairman of the task force, said at a press conference held here Feb. 23 to unveil the report.

While the report includes strong rhetoric—including suggestions that the 3-year-old No Child Left Behind law is unconstitutional—NCSL leaders struck a conciliatory tone when releasing it.

“What we have are specific ideas that we would like to bring to the table,” said Maryland Delegate John A. Hurson, who is the president of the Denver-based NCSL. “The time is right, and we think Congress will work with us to try to make changes.”

Those ideas include granting states greater authority over how to define when a school is making adequate yearly progress, or AYP, a key measure of success under the law. The NCSL also suggests that states be able to reward schools that make progress in improving student achievement even if they haven’t reached their AYP goals in every demographic subgroup, as the law now requires.

Other proposals include dramatically increasing federal financing for the federal law, and commissioning studies to determine the costs of implementing it. The law, a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, is President Bush’s premier initiative in precollegiate education.

Not Budging

So far, though, federal officials appear unwilling to consider the dramatic changes the state legislators want.

A of the “NCSL Task Force on No Child Left Behind Report” has been posted by the . An is also available.

“The report could be interpreted as wanting to reverse the progress we’ve made,” Raymond J. Simon, the Education Department’s assistant secretary for elementary and secondary education, said in a statement.

“No Child Left Behind is bringing new hope and new opportunity to families throughout America,” he added, “and we will not reverse course.”

U.S. Rep. John Boehner, R-Ohio, said in a statement that NCSL’s report was part of an effort to water down the impact of the law.

“Some lobbying groups … want the funding No Child Left Behind is providing, but they don’t want to meet the high standards that come with it,” said Mr. Boehner, the chairman of the House Education and the Workforce Committee. “They want more money and lower standards.”

State officials counter that the NCSL report offers a valid critique of the law.

“They’re saying exactly what needs to be said,” said Betty J. Sternberg, the Connecticut commissioner of education.

Waivers, Changes Sought

In January, Ms. Sternberg requested waivers from the federal Education Department to allow her state to scale back the amount of testing and other requirements of the law. (“States Revive Efforts to Coax NCLB Changes,” Feb. 2, 2005.)

With President Bush starting his second term, and a new secretary of education, Margaret Spellings, in office, a host of organizations are seeking changes to help their members meet the law’s goals.

The National Conference of State Legislatures has a long list of recommendations to change the federal No Child Left Behind Act and the way it is being implemented.

• Congress should assign the U.S. Government Accountability Office to conduct separate studies: one to determine whether the federal education law is an unfunded mandate, and another to calculate the costs of state compliance and of ensuring that all students reach proficiency.

• Congress should almost double current funding levels for programs under the law, enough to provide 40 percent of the national per-pupil funding for every Title I student. The ncsl estimates the cost would be about an additional $18 billion a year.

• The U.S. Department of Education should publish all its decisions on states’ accountability plans under the law and set up an appeals process for states whose requests are denied.

• The law should allow states to determine what interventions to make in Title I schools failing to make adequate yearly progress, instead of following the law’s current prescription that school choice be offered first and supplemental services later.

• The law also should let states determine the percent of special education students to be tested at grade level, and when to require students with limited English proficiency to be tested in English.

SOURCE: National Conference of State Legislatures

The NCSL is the most prominent group thus far to outline so specifically the changes it wants. The panel it convened was a bipartisan group of lawmakers with experience in education. Mr. Saland’s co-chairman, for example, was state Sen. Steve Kelley, a Minnesota Democrat.

Yet the group’s sway is unlikely to be enough to win major changes in the law or the way it’s administered by the Education Department, observers say.

“The [Bush] administration is largely satisfied that it’s accomplished a major change, and they would be loath to open up the legislation,” said William L. Taylor, the chairman of the Citizens Commission on Civil Rights, a Washington-based advocacy group. He supports the law.

Even if the administration were willing to consider legislative changes, it wouldn’t endorse several of the NCSL’s proposals because the changes would undermine the law’s goal of ensuring that all students are achieving at grade level, said one of the law’s architects.

To allow states to set a goal of 100 percent student proficiency at one specific grade level only, as Mr. Kelley suggested at the NCSL’s press conference, would allow some students to fall too far behind, said Sandy Kress, a former education adviser to President Bush.

“We’d open back up the idea that youngsters can fall behind year after year, and then can magically catch up,” Mr. Kress, now an Austin, Texas-based lawyer, said in an interview last week. Mr. Kress was a top negotiator for the White House when the law was being crafted in 2001.

NCSL’s Critique

The National Conference of State Legislatures formed a task force last year to recommend changes that would make it easier to carry out the No Child Left Behind Act. The organization issued the resulting report after collecting testimony from school officials, chief state school officers, and others who must comply with the law.

The NCSL’s executive committee unanimously approved the task force’s report, which offers a long list of recommendations that the state legislators say would improve the law and its implementation.

According to the report, the heart of the problem is the law’s prescriptive nature.

The law, it says, has forced several states either to abandon existing accountability systems that reward growth in student achievement, or to issue reports based on two different systems—which sometimes deliver contradictory results.

Provisions on school choice are also seen as flawed. The law requires districts to offer students transfers to higher-performing schools if their own schools fail to make adequate yearly progress for two consecutive years. After a third year of failing to reach AYP goals, the schools must offer tutoring and other supplementary services.

That sequence is “counterintuitive,” the report argues. The law “shuffles many students between schools before providing individual low-performing students with additional remedial options,” it adds.

On the testing of special education students, the NCSL report says that states should be allowed to set separate AYP goals for students with severe disabilities.

States also should be allowed to decide the percentage of students with disabilities who should be tested against a standard below their grade level.

Some of the complaints could be remedied by changing the rules that govern the law’s implementation, without amending the law itself. The specific requirements for testing, for example, are contained in rules set by the Education Department.

“The focus this year should be on getting the big issues fixed administratively,” Mr. Kress said. “There are some very big areas where states and the federal government can make a lot of progress … without legislative change.”

Changes to the law itself might have to wait until the law’s reauthorization, which is scheduled for 2007.

Constitutional Issues

Although NCSL officials said they hoped the report would open a dialogue with federal officials, the report itself takes a confrontational legal approach.

It speculates that the law is not constitutional, contending that the U.S. Constitution does not explicitly define a role for the federal government in K-12 education.

A 1987 U.S. Supreme Court decision requires the federal government to be “unambiguous” and forbids it to be “coercive” when implementing laws in areas where the Constitution doesn’t explicitly provide for a federal role, the report says.

The report cites several examples to support its contention that the law is ambiguous. For example, it says, there have been protracted periods of negotiation between states and the Department of Education and ongoing amendments to state plans in response to changing federal guidelines, and few models for states to follow when drafting their own plans to comply with the law.

While Mr. Hurson, the NCSL president, said the organization itself has no plans to sue the federal government, he said states could act on their own to challenge the law in court.