The first of some 20 federal investigations into racial disparities in school districts’ disciplinary practices has yielded a for change in the Oakland, Calif., public schools, where black students accounted for 32 percent of enrollment last school year but 63 percent of all suspensions.

The U.S. Department of Education’s office for civil rights called the plan for Oakland unprecedented and a sign of things to come. It described the problems highlighted in Oakland as representative of problems across the country.

Oakland will take a number of steps to address disparities in discipline, including working to find ways to address misbehavior that don’t require students to leave school. The OCR will monitor the district’s efforts through at least the 2016-17 school year.

“This is a landmark resolution. The intent is to suss out and eradicate the causes of discrimination where it may exist,” Russlynn Ali, the department’s assistant secretary for civil rights, said in a phone call with reporters about the Sept. 28 agreement. “It represents a voluntary commitment from the leadership in Oakland to ensure that discipline policies are implemented in a way that is fair and effective, and that they work to change the culture in schools and classrooms.”

An agreement between the Oakland, Calif., school board and the U.S. Department of Education’s office for civil rights requires the school district to take steps to address the suspensions of a disproportionately large number of black students. It says the district should:

• Ensure that misbehavior is addressed in a manner that does not require a student’s removal from school;

• Collaborate with experts on research-based strategies to develop positive school climates that help prevent discrimination when disciplining students;

• Identify students at risk of suspension and provide support services to reduce behavioral difficulties, and continue to provide academic services for students removed from school for disciplinary reasons;

• Review and revise disciplinary policies;

• Train staff members and administrators on disciplinary policies, and develop and implement programs for students and parents that explain the district’s disciplinary policies and behavioral expectations and inform parents of their right to raise concerns and file complaints;

• Conduct an annual survey of students, staff members, community members, and parents regarding discipline;

• Improve data collection so disciplinary policies and practices can be evaluated and best practices can be replicated throughout the district.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education

In a letter accompanying the agreement, the OCR said it found that over time in Oakland, the risk of black students’ being suspended from school had risen. In the 1998-99 school year, black students composed 53 percent of students in the district and 75 percent of students suspended from school. During 2009-10—the year captured by the civil rights data collection—black students made up 33 percent of student enrollment, nearly 64 percent of students suspended from school, and 51 percent of students expelled. Last school year, the statistics were similar, district records show.

During many of those years, the district was mired in financial and leadership woes, and for a time was under state control.

Strategies for Change

had been aware of its problems, said Superintendent Anthony Smith, who took the helm in 2009. The 37,000-student district went so far as to enlist an external group to act as a district watchdog on the issue.

The plan worked out with the OCR, adopted unanimously by the Oakland school board on Sept. 27, will involve in-depth training across the district; additional use of positive behavioral interventions and supports, or PBIS; restorative-justice practices; and “manhood development” classes, designed to help black, male students navigate through school. Preliminary data from the district show that students who take part in those manhood classes improve their attendance and are suspended less often than peers who don’t participate.

Current school board policies don’t require schools to try such strategies before disciplining a student, and the district doesn’t define one key reason for which students can be suspended: “defiance and disruption.” The OCR said that category is the primary reason black students are disciplined. District staff members told the civil rights office that different employees define it in different ways and, the report says, that leeway “allows for the possibility of cultural misinterpretation of behavior and bias to play a role in the discipline decisionmaking process.” Such misunderstanding, staff members said, could escalate a situation and lead to unfair punishment.

“To be able to circle [defiance and disruption] and push a child out of a learning environment is unacceptable,” Mr. Smith said.

Going forward, Oakland teachers will have to describe a student’s behavior, in addition to categorizing it as defiant.

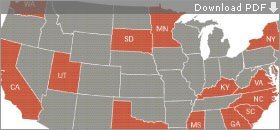

The OCR has undertaken 20 investigations into school discipline practices in 14 states. The probes are part of an Obama administration pledge to work on reducing the overrepresentation of some racial and ethnic groups in discipline cases. The investigations stem from 567 discipline complaints.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education

The federal review ended the same week that California Gov. Jerry Brown signed several bills that aim to change schools’ use of out-of-school suspension, although he vetoed another bill that would have limited schools’ ability to suspend students on those undefined grounds. His decision came weeks after a report found that two-thirds of California school officials were concerned about a differential impact of their disciplinary policies on students from different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Eventually, the middle and high schools targeted in the Oakland plan will have to host annual forums during the school day where students will be able to discuss discipline and share their views on improving disciplinary policies. The district must share the details of each forum with the OCR. Teachers at those schools must also go through training that will provide detailed explanations of the disciplinary code, and when it is and isn’t appropriate to involve a school police officer. And parents will have to be informed of students’ due process rights when the district proposes disciplinary action.

“We have been trying really hard to move away from a zero-tolerance strategy” for discipline, Superintendent Smith said. “When children aren’t in school, they aren’t getting the benefit of the quality instruction. There have been policies that have pushed out boys of color. The waste of so much human potential is unacceptable—not only in Oakland, but across the country.”

Disparate Impact

in May by the Urban Strategies Council, an Oakland-based community-advocacy organization, found that although black boys made up 17 percent of students in Oakland in the 2010-11 school year, they constituted 42 percent of students suspended. Nearly one in 10 black boys in elementary school, one in three in middle school, and one in five in high school were suspended that school year.

Mr. Smith said he believes the measures the district will take, which build on steps taken over the past few years, will shift the culture in the district—and have the potential to improve a troubled city with a history of poverty and violence.

“We think as a public school system we can contribute to a healthier city by addressing this problem,” he said.

The OCR’s 20 investigations, spread across 14 states, are part of an Obama administration pledge to work on reducing the overrepresentation of some racial and ethnic groups in school disciplinary cases.

The results in Oakland show “how OCR can facilitate efforts by districts to move away from discipline practices that leave large and disproportionate numbers of youth on our streets unsupervised to disciplinary interventions that aim to use school exclusion as a measure of last resort,” said Daniel J. Losen, the senior education law and policy associate at the Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“OCR’s involvement through 2017 will help ensure that the undertakings are rigorous, sustained, and well-evaluated,” he said. “Hopefully, many more districts will follow in Oakland’s footsteps.”

This fiscal year, the office for civil rights has received 567 complaints regarding school discipline, Ms. Ali said. “I wanted to be really clear that in this we are not looking to equalize discipline rates,” she said. “This is about how to keep kids in class and ensure that they are learning.”