| |

| Women Superintendents: Few and Far Between |

| In Providence, a Superintendent Follows Her Dream |

| Women Superintendents Credit Support From Colleagues |

| In Washington State, A Welcoming Hand for Women Chiefs |

The Shorewood, Wis., schools had never hired a woman for a high-level job when, in 1981, Barbara Grohe, a 36-year-old assistant superintendent from a nearby district, was picked to succeed veteran schools chief Doug Brown. To the educator’s delight, the fact that she was anything other than a talented administrator seemed to have escaped the notice of the staff and the school board that selected her. But the local newspaper was not so high-minded. The day Ms. Grohe was chosen, the headline read: “Woman Replaces Brown.”

About This Series |

| Study after study shows that a crucial factor in determining whether schools—and school districts—succeed or fail is the quality and stability of their leadership. A growing consensus among educators and policymakers in business, government, and philanthropic circles says that serious attention to the issue is long overdue. With this week’s articles on the shortage of women superintendents, Education Week begins a two-year special project that will examine leadership in education. The Carnegie Corporation of New York is providing financial support for the project. |

Nearly two decades later, the selection of a woman superintendent remains a rarity in the nation’s school districts, if of a lesser order.

For many policy experts, the persistent shortage of women at the highest levels of a field otherwise dominated by women— as teachers, principals, and central-office administrators—is one of the most troubling leadership issues in public education.

“The numbers are not much different from the early part of the century,” said Peg Portscheller, the superintendent of schools in Lake County, Colo. “I find that very depressing.”

A report this year from a consortium of education-leadership groups decried the pace of change for women and minority educators. The nation is “very far behind in attempting to more closely reflect in public school leadership the gender and racial make-up of its students,’' says the report, titled “The Invisible CEO.”

The picture is even more bleak,” it says, “when one sees minimal efforts at the state and national level to even keep track of the problem, let alone to try to solve it.”

Members of minority groups are also seriously underrepresented in leadership positions. Many experts say that women face a unique set of challenges in their attempts to overcome bias.

| Women Superintendents |

|

Includes state, local, and intermediate districts.

NOTE: Percentages vary from “Glass Ceiling” chart due to different data sources.

SOURCE: Jackie M. Blount, Iowa State University. |

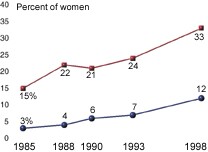

| The Glass Ceiling |

|

KEY

Superintendents

Assistant/associate/deputy/area superintendents

NOTE: Percentages vary from “Women Superintendents” chart due to different data sources.

SOURCE: “The Invisible CEO,” 1999, Superintendents Prepared. |

Much of the problem these days, researchers and educators say, stems as much from subtle notions of gender and leadership as from outright discrimination.

Women constitute about 12 percent of the superintendents in the roughly 14,000 U.S. school districts. That’s up from 2 percent in 1981, when Ms. Grohe got her job in the suburban Milwaukee district, but below the 75 percent of teaching jobs held by women and the 51 percent of the population that is female.

Of the 15 largest districts, only one is headed by a woman, Joan P. Kowal of the 144,000-student Palm Beach County schools in Florida.

“Five years ago, I thought it would take another five years for women to take their place,’' said Paul D. Houston, the executive director of the American Association of School Administrators. “Now I think it will take another 10.”

In many ways, the shortage of women in top education jobs mirrors other fields. In business, where 46 percent of the workforce is female, fewer than 11 percent of corporate officers are women, and only 3 percent are heads of companies, according to recent figures from Catalyst, a New York City-based research and advocacy group for women in business.

But what galls many educators is the contrast between women’s historical contribution to education and their status at its highest levels. Unlike in business or law, for example, women can hardly be called newcomers to the field.

“The [superintendent’s] role is defined by men,” said C. Cryss Brunner, an education professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and one of a small group of researchers who have focused on women leaders in education. “Much like the presidency, we expect to see a man in the office.”

The ‘Glass Ceiling’

Women now make up around half the ranks from which the vast majority of superintendents are drawn: central-office administrators and principals. In district central offices, 57 percent of the professionals are women, as are 41 percent of principals, according to the “Invisible ceo” report from Superintendents Prepared, a group formed nine years ago in Washington to help create a larger and more diverse pool of superintendents.

Those figures suggest that many women are close enough

to see the superintendent’s job clearly, but relatively few crack the barrier.

Many educators and policy experts say a change is long overdue. With baby boom administrators expected to retire in droves over the next decade, many see an opportunity for more women to take their place at the top. More minority women in the job would help public school leadership better reflect the makeup of an increasingly diverse enrollment.

Researchers who have studied the problem and some women educators themselves say that, in the end, many women decide

to live under the glass ceiling rather than struggle against the often unconscious notion that leadership is a male trait. Others refuse to sacrifice their personal lives to a grueling job—a job that was shaped to fit men.

Different Expectations

In the past two decades, dozens of surveys and studies have documented bias against women seeking administrative jobs in education.

“The evil we’ve shown,” said Charol Shakeshaft, an education professor at Hofstra University in Hempstead, N.Y., “would go something like this: Ten people apply for an administrator’s job—five men and five women, with equal credentials—and four of the men and one of the women are chosen for an interview.”

Such circumstances have led many women to conclude that they must be better prepared and do a better job than men to succeed. Even then, the effort might be hopeless.

“Gender is an issue in terms of selection,” said Diana Lam, the superintendent of the Providence, R.I., schools— her fourth job as a district chief. Even in her latest search, she said, “a couple of districts might as well have said, ‘No women need apply.’ ”

“The expectations for women are different, too,” the 51-year-old administrator added. “Women are expected to do twice as much in less time.”

For that reason and for others, women have often short-circuited their ambitions and downplayed their abilities. Evelyn Blose Holman, the superintendent of the 5,000-student Bay Shore, N.Y., schools, remembers interviewing several people for a principal’s job.

“The men didn’t have half the background or the skill the women had, but when you asked the men, they all said they were ready to take it on,’' Ms. Holman recalled. “With the two women, it was: ‘I have more to learn.’ There was more self-analysis.”

Margaret Grogan, a University of Virginia education professor, reports that many women have firm notions about what’s needed to get the top job. In a 1993-94 study of 27 women aiming to be superintendents, Ms. Grogan found that most believed it would be futile to try for the job without going down the most conventional path—from teacher to principal to assistant superintendent. They believed that to establish their competence on a par with men, they also needed a doctoral degree, sponsors, professional visibility, and experience dealing with business issues.

Shifting Demands

But some women who seek and gain the experience and credentials that would qualify them for a superintendent’s job decide against it.

“The primary reason that women say they don’t want to be superintendent is it’s too big a price to pay,’' Ms. Shakeshaft said. When women weigh the possible rewards against the costs, their conclusion is likely to differ from that of their male counterparts. The rewards may be less because of their lower need for status and self-esteem, Ms. Shakeshaft suggested, and their greater need to succeed as spouses, parents, and friends.

“Women tend to have more responsibility for the home and family,” she said.

As a result, the job will shut out more women than men until the work no longer consumes private life or until men and women share equally in family responsibilities.

Ms. Brunner of the University of Wisconsin found that among 12 successful women superintendents she studied, several said the job had cost them their marriages.

“I was married when I took over in Wicomico County [Md.], and I’m divorced now,’' said Ms. Holman, the Bay Shore, N.Y., superintendent. Her then- husband lived in Baltimore while she took up residence in the rural district, some 100 miles away.

“I don’t have children,” Ms. Holman added. “I think it’s very difficult for men as well as for women superintendents to be fair to their families.”

Changing the Job

Women who have risen to the superintendent’s job have dealt with this set of problems in various ways. Some have delayed their entry into administration until their children are older—one reason search consultants say that, on average, women start their first jobs as superintendent at an older age than men.

Others, such as Diana Lam and Barbara Grohe, have husbands who have provided much of the logistical flexibility in their marriages. And a few, such as Paula C. Butterfield, the superintendent for Mercer Island, Wash., have focused on redefining the job so that the well-being of the superintendent, and of other administrators, is seen as contributing to the success of the organization.

To some extent, argues Ms. Brunner, most women who make a success of the superintendency are transforming the traditional conception of the job. That’s because they have to confront a serious cultural contradiction: The job is powerful, yet women, in the minds of many people, should not be. According to this set of beliefs, a powerful woman is distasteful, unfeminine, even ludicrous.

A strong woman, Ms. Brunner said, can make both men and women uncomfortable by challenging the conventional understanding— unless, that is, she finds a way to exercise power that is recognizably different from the norm.

Successful women superintendents typically “remain feminine while succeeding in a masculinized role,’' she added, “which is an incredible negotiation.”

Part of doing that is redefining power, some research suggests. Women superintendents are more likely than men to speak about and use power in ways that emphasize working with others for common ends. Rather than “command and control,” these women expect to communicate and collaborate.

Women often take this approach to remain true to themselves, they say, but it is also practical.

Patricia A. Schmuck, a retired professor of education at Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Ore., and one of the first researchers to study women school leaders, cautions against seeing the differences between men and women in this realm as inherent. “There may be a different approach because women finally learn that what works for men doesn’t work for them,” she said.

And, ironically, even those forging the new style are not likely to dwell on the rough spots or cast themselves as feminists.

That disturbs many of the researchers, who see themselves as advocates for women, but the scholars are also sympathetic to the real-life concerns of administrators in the field.

“They have figured out stuff, but they don’t want to focus on [the condition of women]—they have other things to do,” Ms. Schmuck said. “Things like pass the school budget.”

Ms. Holman agrees with that perspective. “I don’t think it’s healthy to look at [job opportunities] as a matter of race or sex,” the 59-year-old superintendent said. “I believe if you do the very best, people are going to come seeking your expertise because there is not enough expertise out there.”

Playing to Strengths

That expertise has never been more in demand, especially if it includes the collaborative approach to leadership that is now being commended to men and women alike, said Mr. Houston of the Arlington, Va.-based administrators’ organization.

That approach, he said, is better suited to the community- building role that superintendents must play as their constituencies and their students grow more racially and ethnically diverse.

And some of the other strengths that women often bring to the superintendent’s office are particulary valued these days, notably knowledge of curriculum and teaching and a focus on children.

The job “is playing much more to their strengths” than in the past, Mr. Houston said, when the superintendent was supposed to be “a guy who started as a coach with keys dangling from his belt.”

Still, history offers a cautionary tale for those who predict steady improvement in the proportion of women running public school districts. For much of this century, the percentage declined, and only since the 1980s has it begun to inch back up.

In 1930, amid a wave of political activism among women (who won the vote in 1920) and spurred by the dominance of their sex in teaching, women made up about 11 percent of the nation’s superintendents. It has taken nearly 70 years for the percentage to return even to that level.

Starting in about 1950, the numbers plummeted, reaching just 3 percent in 1970, according to Jackie M. Blount, whose 1998 book, Destined to Rule the 69��ý, chronicles the trends of women in working as superintendents.

“There looked like a time when women were going to take on school administration, and then something happened,” said Ms. Blount, an education professor at Iowa State University. Indeed, the title of her book is drawn from a speech given by Ella Flagg Young, who in 1909 became the first woman to head a big-city school system. That year, the Chicago superintendent declared optimistically that “women are destined to rule the schools of every city.”

What happened was a whole tide of social and cultural factors that conspired to take women out of the workplace and make them seem, once again, inadequate for the tasks of administration.

The rise of educational administration as a distinct profession in the earlier years of the century, for instance, helped make men the managers and women—teachers—the workers.

The Future

Many experts say the lack of data itself is a major hindrance to improving the situation. No fully reliable statistics exist, for example, on the gender and ethnicity of school administrators.

“There is almost no national knowledge base on American school superintendents,” says the report from Superintendents Prepared.

At the same time, the reduction in recent years of support for affirmative action worries many advocates for women. Preparation programs in universities, including doctoral programs in educational administration, currently have enrollments that are at least 50 percent female, but only about a quarter of their faculty members are women.

Some critics say that colleges and universities have been slow to recognize and address the problem, though that could change both with a shift in faculty and more conscious efforts, already under way at some institutions.

Women benefit from support networks both in looking for a job and in surviving one. Though not exclusively for women, programs such as the Danforth Foundation’s Forum for the American School Superintendent, based in St. Louis, and the Urban Superintendents program at Harvard University’s graduate school of education, help women make connections that inspire and sustain them.

Once a bastion of male authority, the aasa has in recent years added a formal women’s committee to its structure and sponsors an annual conference for women administrators.

Those activities, along with an informal women’s caucus, have helped women to gain visibility within the 14,000-member organization, which represents superintendents and other district administrators.

But that may not be enough to overcome some of the other pressures women face as they move up the district ladder, according to research by Carolyn Riehl and Mark A. Byrd of the University of Michigan.

In 1997, they published a study, drawn from a federal survey done in 1987-88 of 4,800 teachers, some of whom became principals and assistant principals during those two years. Their research suggests that while a degree in administration and experience as

an administrator increased the chances of becoming an administrator, having a spouse decreased the women’s chances but not the men’s of becoming a secondary-school administrator.

Overall, the probability that women would become principals or assistant principals—a key step to the superintendency—

remained far below that of men.

A study released this year, though, sees promise of improvement. Three researchers— Susan Bon Reis of Pennsylvania State University, I. Philip Young of Ohio State University, and James C. Jury of The Citadel in Charleston, S.C.—asked 150 high school principals to evaluate documents from hypothetical male and female applicants for an assistant principal’s job.

To the researchers’ surprise, the women won significantly more favorable marks than the men, whether the evaluators themselves were male or female.

The findings, the researchers write, “point to improved odds for women who want to advance into school administrative positions.’'

Floretta D. McKenzie, an education consultant and a former superintendent of the District of Columbia schools, agrees with that conclusion, but offers a different reason. “Because the pool [of candidates] is getting smaller, I think women are going to have a better chance of getting in.”