69��ý spend an average of 10 days out of the school year taking district-mandated tests and nine days taking state-required tests, according to the Center on Education Policy. Over 12 years of schooling, that adds up to nearly four months of a young person’s life.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

That number does not include teacher-made tests, quizzes, final exams, many college-admissions tests and pretests; nor does it account for the amount of time teachers spend preparing students to take all those exams.

But the estimate, drawn from a nationwide 2015 survey of more than 3,000 teachers, provides a starting point for wrapping one’s mind around the amount of testing students actually do in schools. It also points to the high priority that educators and policymakers put on tests and the information they yield. While most of the teachers who responded to the center survey thought states and districts should cut back on the time students spend taking mandated tests, only a fraction of them wanted to dump those tests altogether.

Such tensions help keep the national testing landscape in a constant state of flux. In the search for better assessments, more authentic tests, or assessments that can drive better-quality instruction, new forms of testing come and go.

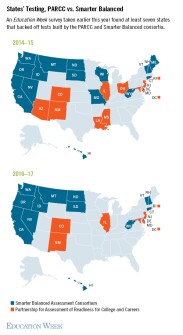

Much of that change in recent years has been driven by efforts to implement tests to measure students’ progress in mastering the Common Core State Standards in math and English/language arts. Between 2010 and 2011, 45 states had adopted the standards. Within a few years, states’ unity began to crumble. By the 2014-15 school year, as the tests were put in place, 27 states were using standards-aligned assessments developed by either Smarter Balanced or the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Career consortia. The number dwindled to 20 this school year.

Ironically, as states backed off those assessment commitments, the prospect of annual testing ramped up for one subgroup of students: English-language learners.

The Every Student Succeeds Act, passed in 2015, requires states to test students in English-proficiency each year and to standardize criteria for determining when students no longer need language-support services.

The new federal education law injects some flexibility—and tumult—into the testing world by inviting states to use college-admissions tests like the ACT or SAT for federal accountability purposes. Twelve states are already doing that, and 13 more are requiring all high school students to take one of the two tests.

The scrambling going on around the college admissions tests obscures a milestone in that sector that passed in 2013 with little fanfare: For the first time that year, more students took the ACT than they did the SAT.

The inclusion of required college-admissions testing in states’ accountability indicators is part of a push to ensure that all students graduate, as the expression goes, “college- and career-ready.” But how should schools measure student’s progress on the career part? That’s a difficult question, and experts are skeptical about the prospects for assessments that reliably predict whether a student has the necessary skills to succeed in the workforce.

Elsewhere on the curriculum standards front, assessments aligned with new science standards are gaining traction, albeit slowly. Tests aligned with the new Next Generation Science Standards should require students to “show us how they know, not just what they know,” as one testing expert put it, and that entails a range of logistical, technical, and financial challenges for states.

Meanwhile, in the classroom, formative assessments are going digital in a big way. Formative assessments are meant to provide a way for teachers to quickly diagnose whether students are “getting it” so they can tailor their instruction accordingly. Teachers can do that by asking students to answer questions or take a paper-and-pencil quiz or they can turn to the growing number of digital products on the market that allow them to gather, track, and analyze their students’ progress. That sector of the market is currently booming, with experts predicting growth rates of 30 percent between 2013 and 2020.

A big downside to tests, especially summative tests where the stakes are high, is the anxiety they can create in students. “People who are anxious in general often get test anxiety, yes, but a lot of people who are not particularly anxious can still develop stress around tests in different subjects” like mathematics, said Mark Greenberg, a Pennsylvania State University researcher.

He is among a growing number of educators and researchers looking for ways to help students better cope with test-related stresses. Perhaps the most interesting example of these efforts is in Austin, Texas, where a full-time “mindfulness director” employed by the district trains teachers in anti-stress techniques they can pass on to students.

In the end, it all comes down to the students. What would assessments look like if they were designed by students themselves? Would students become more engaged in their learning? A network of public schools in Virginia is at work answering those questions right now. While results from their experiments are not in yet, teachers do say that students seem to be more involved in the learning. Stay tuned.