Here, in the nation’s largest school system, the face of the typical student is, increasingly, that of a child whose parents were born somewhere other than the United States—and, in many cases, someone who enters school speaking little or no English.

More than half of New York City’s nearly 1 million public school students have at least one foreign-born parent. This school year, 148,000 students are classified as English-language learners, or ELLs—up from 109,000 in the 1990-91 school year. By the end of this school year, about 30,000 more such students will have enrolled, the city education department projects.

Given such demographics, New York City offers a barometer of the pressures facing school systems nationally—whether urban or rural—in working to educate English-language learners amid the push for standards-based school reform.

The forecast, across the country, is cloudy at best.

Whether measured by state tests required under the federal No Child Left Behind Act or by the National Assessment of Educational Progress—also known as “the nation’s report card”—English-language learners lag far behind their fluent English-speaking peers in both math and reading proficiency.

And those deficits—a gap in the proportion of students deemed proficient on naep of 25.2 points in math and 24.8 points in reading in 2007, when 4th and 8th graders’ scores are combined—follow a surge in the ELL population in recent years. The number of English-learners nationwide rose about 57 percent, to 5.1 million students, in the decade ending in 2005, according to the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition.

The increase in enrollment and a shift in migration patterns that have led many immigrant families to settle in suburban and rural communities strain the resources both of districts long familiar with English-learners and those with little such experience.

The impact can be felt from the central office, where administrators scramble to find funding for specialized classes and English-as-a-second-language teachers, to the classroom, where teachers must find ways to help ELLs learn course content as well as a new language.

This year’s edition of Quality Counts takes a look at the academic, instructional, and financial hurdles facing the nation’s public school systems in educating English-learners in the era of NCLB.

Educators and advocates for English-learners say the 7-year-old federal education law has shone a less-than-flattering spotlight on how well public schools are doing in teaching such students English and the content they need to become high school graduates.

Even in states like California that have a long history of educating children of immigrants and that enroll a large proportion of the nation’s English-learners, such students lag significantly behind non-ELLs on standardized tests.

English-language learners of school-going age tend to be younger than members of the non-ELL population. That pattern may result from high birth rates among language-minority populations, high immigration rates among the youngest ELL youths, and the tendency to acquire proficiency with the English language over time.

SOURCE: EPE Research Center, 2009. Analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2005-2007).

But because the NCLB law requires that English-learners be tracked as a subgroup for accountability purposes, educators now more seriously weigh what is working, what is not working, and what could work with such students. And that is great progress, say experts in the field.

Mixed Picture

New York City’s experience is instructive.

Only 23.6 percent of students who start 9th grade in the city as ELLs graduate four years later, although some continue their schooling and receive diplomas after that. The four-year dropout rate for ELLs is 41.8 percent.

But, says Maria Santos, the head of the city department of education’s ELL office, other indicators show that some progress is being made through the department’s deliberate effort to ensure that English-learners have access to the regular core curriculum—something she contends many didn’t have before 2003.

For example, the percentage of ELLs in grades 3-8 scoring “proficient” in mathematics on the state’s regular exam in that subject had grown to 58.6 percent in 2008, from just 16.7 percent in 2003, Santos says.

Meanwhile, more students are moving out of the first of four recognized levels of English proficiency—and moving out more quickly—than previously.

The families of school-age English-language learners are consistently more socioeconomically disadvantaged than those of their peers. ELL youths are half as likely to have a parent with a two- or four-year college degree and much more likely to live in a low-income household. While two-thirds of ELL youths have a parent who holds a steady job, their parents typically earn much less than those of non-English-language learners.

SOURCE: EPE Research Center, 2009. Analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2005-2007).

On the 2008 administration of New York state’s English-language-proficiency test, 13.4 percent of ELLs attained proficiency in the language, up from 12 percent the previous year. And ELLs’ scores on the state’s regular reading test are steadily increasing. In 2008, for example, 22.6 percent of ELLs in grades 3-8 scored proficient on the state’s reading test, up from 3.9 percent in 2003. Santos attributes such progress to extensive professional development for mainstream teachers on how to work with English-learners and to increased collaboration between English-as-a-second-language teachers and content-area teachers.

In addition, with Santos’ leadership, the New York City district is looking at ELLs as a very diverse population, made up of different subgroups requiring different strategies. The system has teamed up, for example, with researchers at the City University of New York to explore approaches for better educating “students with interrupted formal education,” or SIFE. The city’s 15,500 English-language learners who fall into that subgroup are immigrant students who have missed at least two years of schooling or who are lagging behind grade level by at least two years.

Long-Term ELLs

The school system and researchers are also working together on how to better serve “long-term English-language learners,” defined as students who have been in the district’s special programs to learn English for six years or more and still haven’t tested as fluent. The district counts 20,000 students in that category, but acknowledges the true number is likely much higher.

Even within the ELL subgroup, there is a great deal of diversity. That variety is illustrated by the 23 SIFE students who attend English Language Learners and International Support Preparatory Academy, a school that opened in the Bronx this school year to serve immigrant students age 16 or older.

Sixteen-year-old Rita Fugar missed many school days in her home country, Ghana, because of an asthma condition; she says that in the United States, the condition is no longer causing her to miss school.

Mariela Estrella, 17, missed school while moving back and forth between the Dominican Republic and the United States—and lost a year of school in the United States after she had a baby.

Slightly more than one-third of ELL youths in the United States are foreign-born, compared with 4 percent of their non-ELL peers. Nearly half of all English-language learners are second-generation Americans, meaning they are native-born with at least one parent born outside the United States or its territories. Seventeen percent of ELLs are third-generation Americans with both parents born in the United States. Ninety-six percent of non-ELL youth are native-born.

SOURCE: EPE Research Center, 2009. Analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2005-2007).

Morry Bamba, 18, is considered a SIFE student because he attended school for the first time when he arrived in the United States from Guinea, in West Africa, at age 15.

The school was awarded a $100,000 grant for this school year from the New York City Department of Education that pays for extra help for such students. Even before the school got the grant, a curriculum specialist was working one-on-one with teachers on how to make the school’s curriculum accessible. And a certified teacher, Annie Smith, was spending two days a week in the school, giving SIFE students special help in class.

Districtwide, strategies for helping SIFE students catch up have included extended-day programs, such as after-school programs.

With the long-term English-learners, the district is taking a different tack. One strategy involves providing Advanced Placement Spanish courses for some students to capitalize on their Spanish knowledge and to increase their motivation, according to Santos.

She credits the accountability provisions of the No Child Left Behind law with creating a political climate that made it easier to push through measures to improve the education of ELLs.

“Certainly, the accountability environment helps,” she says. “Everybody has to target the standards for all kids. ... What we do in the city is help our schools get to the standards.”

Most English-language learners from the ages of 5 to 17 are Hispanic, while 14 percent are white and 13 percent are of Asian or Pacific Islander descent. The majority of the school-age non-ELL population is non-Hispanic white.

SOURCE: EPE Research Center, 2009. Analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2005-2007).

But she says the law also has indirectly discouraged New York City schools from providing bilingual education because educators feel pressured to teach students English as soon as possible so they can do well on standardized state tests in English. The number of students in bilingual programs in the city has declined. Currently, 26 percent of ELLs are in bilingual programs, down from 39 percent in 2002.

NCLB: Reviews Vary

Many experts agree that English-learners have been helped by the NCLB law’s attention. But they say the federal law hasn’t always spurred the kind of response needed for such a diverse group of students.

“There’s more variation in terms of what kids need within the English-learner population compared to the non-English-learner population,” says Robert Linquanti, a project director and a senior research associate at WestEd, an education research organization based in San Francisco. “The tendency among policymakers and some educators is to see English-learners as a monolithic group.”

In reality, he says, “most [ELLs] are born in the United States, and some come from other countries. Some are at grade level and highly educated in their native language. Others are not. ... We need to understand the subgroups within our population.”

Deborah J. Short, a senior researcher at the Washington-based Center for Applied Linguistics and a member of the advisory panel for Quality Counts 2009, says she’s surprised that NCLB hasn’t had more of an effect on teacher-preparation programs or teacher-certification requirements.

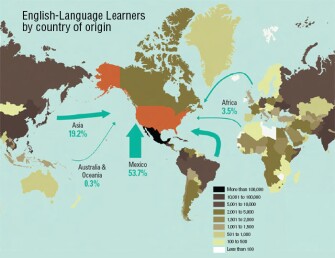

Foreign-born English-language learners of school age hail from more than 200 countries that span every corner of the globe, according to an original analysis by the EPE Research Center. Mexico is the largest single country of origin, accounting for nearly 54 percent of all ELL youths born outside the United States or its territories. Large groups also immigrate from elsewhere in the Americas and from Asia. However, about two-thirds of all English-language learners are native-born.

SOURCE: EPE Research Center, 2009. Analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2005-2007).

“We’re just putting teachers out there who aren’t prepared to work with ELLs in their classrooms,” she says.

Experts also point to various aspects of the accountability provisions of the federal education law that they don’t believe are well thought out for English-language learners.

James Crawford, a longtime writer about language issues and the executive director of the Washington-based Institute for Language and Education Policy, says the high-stakes-testing requirements of NCLB have led to “drill-and-kill approaches” to instruction. “The schools are under tremendous pressure to pump up test scores, whether kids are learning or not,” he says.

Crawford, who formerly covered English-learners as a reporter for Education Week, is particularly critical of states’ use of their regular math and reading tests to assess ELLs for accountability purposes, because the tests aren’t designed for those students. He says the English-language-proficiency tests are “more reasonable,” but they shouldn’t be used for accountability purposes. “The problem is that all kids don’t learn at the same rate,” he says.

Linquanti also believes that testing and accountability for English-learners have to be better thought out, and he hopes that might happen in the overdue reauthorization of the NCLB law. Adequate yearly progress, a key measurement of schools’ success under the law, “has allowed the achievement gap to be highlighted, but there’s this issue of ‘Are we accurately measuring what they know?’ ” he says. “What’s problematic is how their scores count.”

He also criticizes the requirement that accountability decisions be based on the goal that 100 percent of all students—including ELLs—be academically proficient by the end of the 2013-14 school year. Linquanti views that goal as unattainable and says it undermines the credibility of the law’s accountability provisions.

“A lot of good has come out of NCLB for English-learners,” but such gains are at risk, he says.

Progress Debated

Kathleen Leos oversaw implementation of the No Child Left Behind law for ELLs as the director of the office of English-language acquisition of the U.S. Department of Education before leaving to work in the private sector in October 2007. She believes NCLB has helped states make great strides in creating an infrastructure to support English-learners. When President George W. Bush signed the legislation into law on Jan. 8, 2002, she says, “for ELLs, there was no state that had a uniform system that addressed language-development needs and access to the content for ELLs.”

Leos says that the key to a strong state program is for English-language-development standards to be aligned with academic-content standards and for the curriculum for ELLs also to be aligned with those standards. In addition, she says, all teachers who work with ELLs must be equipped to teach language development and content at the same time.

“The information at the state level to put in a uniform system has not reached the district level,” she says. “They need to get the changes to the district and into the classroom. That’s the greatest disconnect now.”

But others believe the solution is more complicated.

Patricia Gándara, an education professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, says she doesn’t see evidence that ELLs are yet ensured access to the same core curriculum as other students.

H. Gary Cook, a research scientist at the Wisconsin Center for Education Research, part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says that while “aligning the standards is a nice thing to say, I’ve tried to do it, and it’s really difficult.” He says that while NCLB has moved states in a positive direction, “when you talk about the school and school district level, you can find pockets of excellence and of mediocrity.”

Reports from large school systems and states seem to bear that perception out.

A federal judge in Texas, for example, concluded this school year that while programs at the elementary level statewide seemed to be serving ELLs adequately, programs at the secondary level violated federal law because of their ineffectiveness. The Texas Education Agency is appealing the decision.

The St. Paul school district, in Minnesota, was commended in 2006 by the Washington-based Council of the Great City 69��ý for nearly closing the achievement gap between ELLs and non-ELLs. But while St. Paul’s English-learners still significantly outperform such students in other Minnesota school districts on average, the district has been unable to keep that gap from widening again as the state has changed its tests.

In New York City, where some sets of data show strong academic gains for ELLs, their graduation rate has worsened. But Santos, the district’s English-learner administrator, sees signs of hope.

“We know that more of our kids who start with us in kindergarten are exiting the [elementary ELL] program with strong foundations in English and core academics,” she says. “This group of kids is moving up through the system. They will be in high school pretty soon, and they are going to start turning this data around.”