Author’s note (6/17/19): When I wrote this column, I failed to disclose to EdWeek and to my readers that I was part of a paid fellowship during the 2018-2019 school year involving Empatico, the organization I reference in this piece. The fellowship involved a partnership between the National Network of State Teachers of the Year and Empatico, a nonprofit that provides a free online platform similar to Skype for teachers to connect their students with children in other countries or parts of the U.S. The fellowship involved 20 teachers who did a yearlong classroom exchange, engaged in a research project to measure the impact on the development of empathy in their students, and spread the word about their experience with Empatico through weekly Tweets, open houses at their schools, and written pieces like this column. Each teacher was paid an honorarium of $375 in December 2018 and $375 in May 2019 for their participation. I wrongly assumed that NNSTOY had communicated with EdWeek about the nature of the fellowship in advance of submitting posts by teachers referencing Empatico, and I failed to disclose the fact that I received payments through NNSTOY for my participation. I deeply regret the oversight.

I was teaching at P.S. 192 in New York City on Sept. 11, 2001. In the days following the terrorist attack, my students dealt with the fear and sorrow you would expect. Nine-year-old Clara told me, “I feel sad and scared all the time now. Every time I see a plane up in the sky, I think it’s going to crash down on my head.”

My 4th graders also had a more insidious reaction to the attack. This secondary response took hold after weeks of inundation by media images like the grainy black-and-white photos of the hijackers’ bearded faces. One Monday morning, Luis told me, “I was sitting on the subway with my mom this weekend and I saw a guy with a turban in the seat across from us. I was scared he might do something to us.”

These kinds of comments, expressing fear and anger toward anyone who looked Middle Eastern and potentially Muslim, disturbed me deeply. Almost all of my students were Dominican or Puerto Rican, as were the vast majority of their classmates and neighbors. Most of them didn’t know any Middle Eastern or Muslim people to provide a counter-narrative to the images and messages flooding the media in the aftermath of 9/11. I wasn’t sure how to address my students’ newly manufactured stereotypes, but I knew I needed to figure it out.

We began with a K-W-L (know, want to know, learned) chart, beginning with what students “knew” about Muslims. Their responses were shocking.

“They hate us.” “They’re jealous of our freedom.” “They’re ugly.” “They live in caves.”

Every single comment on the list was negative. After we had completed the first two columns of the K-W-L chart, we read a series of books about Muslim children in the Middle East and elsewhere. We began with by Florence Parry Heide, about a boy in Egypt who has just learned how to write his name in Arabic.

After each book, we would revisit our list. I asked my class questions: “Did the boy in that book live in a cave?” (“No,” they said. “He lived in a regular house.”) “If that kid in Egypt met our class, do you think he would hate us?” (“No,” they told me. “He’d probably be our friend.”)

I learned that year that young children have a huge advantage over adults when it comes to acknowledging, questioning, and changing their biases. Children are often honest in a way that adults struggle to be. Most young kids will tell you exactly what they think and feel about the world, with very little self-censorship. Their stereotypes are also easier to uproot, especially when they’re planted in the shallow soil of second-hand sources like media images or overheard comments, rather than in direct experience with people from those groups.

My students let go of their ugliest stereotypes about Muslims and Arab-Americans in a matter of days, with no more effort than it takes to release the string of a balloon and watch it vanish into the sky.

Bridging Difference

In the 17 years since that experience, I have heard more ugly things come from the mouths of children as young as 6 years old. I have seen some students recoil in disgust at the idea of two men or two women falling in love. A 2nd grader once told me, as casually as mentioning an aversion to guacamole, “I hate black people.”

But these children, when challenged to think through the shaky foundation of their stereotypes, have also let go of their biases as readily as my 4th graders in New York relinquished their sweeping fear of Muslims. As said, “Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.”

At this year’s conference, I learned about a way to connect kids directly—not just through Read Alouds or guest speakers—with children whose lives and cultural backgrounds are strikingly different from their own.

is an online tool that allows for Skype-style interactions between classes of children ages 7 to 11. You might be paired up with a class in Mexico, Ghana, China, or Brazil. Or you might be partnered with a class of children in another part of the United States, separated from your own students not only by geographic distance but by socioeconomic and racial divides. Empatico’s exchanges are free, including the resources for lesson plans with activities to do before, during, and after the conversations with your partner class.

My partner teacher and her class live about 1,000 miles away in New Jersey. They come from more affluent backgrounds than my own 2nd graders, who all live in poverty and almost all speak English as a second language.

Sometimes our conversations with the kids in New Jersey touch directly on cultural differences. Two Indian students in their class shared the languages they speak at home and told us a little about how they celebrate Diwali. In our first meeting, the class in New Jersey asked if we would teach them how to speak Spanish. Last week my student Ana asked our new friends, several of whom are Jewish, “What foods do you eat during Hanukkah, and what do you do to celebrate?”

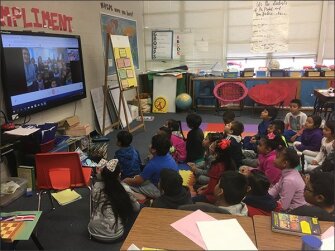

We have also exchanged favorite sports (my Arkansan, predominantly Latino kids had never heard of lacrosse), hobbies (“playing video games” topped the list for both classes), and ice cream flavors (a majority in both classes love cookies and cream). The first time we met, one of my students wanted to know if the kids in New Jersey had heard of Smashball. They hadn’t, but when he started describing it to the kids on the screen, they got excited and told us, “We play that, too, but we call it Gagaball!”

Photo taken by the author in his classroom.

These lighter exchanges might seem silly, and they often are. But when I think about my own cross-cultural experiences in China, Europe, and West Africa, bridges with people across the world were often built on these little discoveries of differences and common ground: Exchanging a jar of Jif peanut butter for a jar of Nutella with my 16-year-old host brother in southern France. Playing soccer with homeless kids in West Africa, with two broken cinder blocks to serve as the goal.

Discovering common ground is crucial within our own country, too, which has been riven in the past two years by divisions based on race, class, religion, country of origin, and virtually any other category you can think of. American , , and remain deeply segregated. We have to find ways for children who will not meet one another in school, church, or while playing on the same block to connect face-to-face in another way.

Friendships between individuals of different backgrounds won’t bridge societal divides on their own. But when I look at the issues that have divided our nation over the past couple of years, from the “Muslim ban” to police shootings of black men to the separation of families at the U.S.-Mexico border, I see a common thread. The people who make, support, and tolerate harmful policies don’t see the humanity of those they are hurting as being quite equal to their own.

A Latina girl in Arkansas asking a Jewish girl in New Jersey to tell her how to make latkes might seem like a small step toward recognizing our shared humanity. But every year I witness the deep goodness of children. I see them choose to be kind, to be curious, to play together at recess and invite each other to playdates on the weekend—even when their skin color, the size of their family’s house, or the language they speak at home is not the same. I see children show us—we adults who have such a hard time admitting to our biases, let alone changing them—the way forward.

Ruby Bridges, one of the first black students to integrate an all-white elementary school, has said, Helping young children realize how much they have in common is a strong antidote to that disease.

To sign up for a partner class in another part of the country or across the world, go to . For sample titles and guidance on selecting books that help break down stereotypes, check out this resource from Teaching For Change: