A slow but significant change has been taking place in the early reading world over the past year, loosening the grip that some long-used, but unproven, instructional techniques have held over the field for decades.

Big names—like Lucy Calkins, of the Teachers College 69��ý and Writing Project, and author and literacy specialist Jennifer Serravallo—have recently released updates to their published materials or announced impending rewrites that change how they instruct students to decipher words.

69��ý researchers say they find these industry moves encouraging. “The fact that there’s an awareness ... that’s a step in the right direction,” said Claude Goldenberg, a professor emeritus at Stanford University who studies early literacy development in English-language learners.

But they also cautioned that this narrow change in materials won’t necessarily lead to large shifts in instructional practice, and that more needs to be done to support teachers of the youngest learners in developing kids’ early reading skills—especially after several years of disrupted, pandemic-era schooling.

The shifts curriculum providers are making mainly have to do with how teachers instruct students in word-level reading—that is, decoding the words on the page into spoken language.

Much of teacher training and many classroom materials adhere to the theory that children should use multiple sources of information, or cues—the letters in a word, but also the pictures on the page or the flow of the sentence—to make a prediction about what the word is.

But evidence from cognitive psychology and neuroscience research has long shown that good readers attend to the letters in the words to identify what words say. Research has demonstrated that instructing students on how to crack the code of written language is one of the most effective ways to get them reading words.

And while it’s important to teach young kids about story structure and syntax, and to have rich conversations about illustrations in picture books, children shouldn’t rely on those sources of information to guess at what the words on the page say, said Goldenberg.

“There’s a very subtle, nuanced, delicate dance in sequencing,” he said. “It’s that kind of delicate balance that I see completely missing from programs that try to do everything all at once.”

Now, some publishers are trying to make a shift in how they integrate, sequence, and attend to foundational skills instruction. But there are open questions about how these changes in materials will change practice in classrooms.

“We see ourselves at a hinge moment,” said Maryanne Wolf, the director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies, and the author of several seminal books about how the brain learns to read. “The separation of two doors on reading has been not just unfortunate, but even tragic, leaving behind children who have needed desperately a different form of instruction.”

A public conversation about reading science led to materials changes

The research motivating these changes isn’t new.

In 2000, a panel of experts was convened by the federal government to evaluate the evidence on reading instruction. One of the takeaways from the National 69��ý Panel’s report was that explicitly teaching about the sounds in words, and how those sounds matched up to written letters, would help children learn to read. This finding drove policy changes in the early 2000s, most notably the introduction of 69��ý First, a federally funded program that emphasized phonemic awareness and phonics instruction.

The program had mixed results, leading to some improvements in children’s word-reading ability, but not in their reading comprehension. In its wake, many schools and teacher education programs adopted a model called balanced literacy—aiming to balance foundational skills instruction with more focus on stories, comprehension, and developing a love of reading.

But in 2018, reporter Emily Hanford of APM Reports brought to light that in many balanced literacy classrooms, —how written letters match up to spoken sounds—and were being encouraged to use other strategies to guess at words. Without this foundational instruction, many students never figure out how to decode the printed words on the page.

Hanford’s documentaries—as well as a slew of coverage from Education Week and other outlets—ignited a firestorm of controversy, with some teachers outraged that they had never learned how to teach phonics in their teacher preparation programs, and others pushing back with a defense of their teaching methods. In the several years that followed, more states started to mandate teacher training in, and classroom attention to, foundational skills instruction in an effort to adhere to what came to be referred to as the “science of reading.”

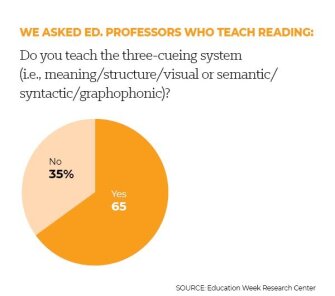

But these word-guessing strategies are also deeply embedded in much of early reading curricula, as Education Week reporting has shown. Many programs and teacher guides encourage prompting students to rely on a story’s meaning and structure, as well as the letters on the page, to predict what words will say—a strategy known as three-cueing or MSV (for meaning, structure, and visual). And while most curricula incorporate phonics instruction, it’s often “competing for teachers’ and children’s attention and time,” said Goldenberg.

Now, some influential publishers are starting to make changes.

This summer, Serravallo released an update to part of her popular The 69��ý Strategies Book, revising strategies for word-level reading to emphasize decoding and abandoning techniques that encourage students to guess at words. Early this year, literacy consultants Jan Burkins and Kari Yates released a new book, Shifting the Balance, that offers “ways to bring the science of reading into the balanced literacy classroom.”

And Calkins, of the Teachers College 69��ý and Writing Project, has announced upcoming revisions to her popular Units of Study for Teaching 69��ý program. The changes, Calkins said, will incorporate more explicit instruction in phonics and remove some prompts that ask students to look to pictures or context for word identification.

I think teachers want to learn, and … I can model that it's OK to say, ‘There were a few things I think I got wrong, and I'm learning about them.’

At the same time, several more states have passed laws mandating that schools teach the “science of reading”—laws that would affect curricula and materials.

Mark Seidenberg, a cognitive scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies reading, said the publishers’ changes are a response to these new policy priorities. But he worries that the revisions will be surface level, only shifting instruction enough to “satisfy the stipulations in those laws,” he said.

“They can’t change their materials too much, because they’ll lose their followers,” Seidenberg said. “What’s going to come out of this? Minimal changes that are enough to satisfy [these] states.”

Wiley Blevins, an educational consultant and author of several books on phonics teaching, understands the critiques, and the skepticism, that some experts are expressing about these changes: “I get the anger, because we’re talking about kids’ lives. We’re talking about their futures.” But he sees more reason for optimism, in teachers who may now have more guidance to “do better for their students.”

Lucy Calkins outlines upcoming changes to Units of Study

In some cases, this guidance for teachers is still forthcoming. Calkins’ 69��ý and Writing Project, a workshop-based program that publishes a reading curriculum used by about 16 percent of early elementary and special education teachers, according to data gathered by Education Week, is planning to release updated materials in summer 2022. (The timeline has been pushed back due to COVID-related production delays, Calkins said.)

The planned update reflects a shift in approach for the group. In November 2019, Calkins released a statement pushing back on those whom she described as “the phonics-centric people who are calling themselves ‘the science of reading.’” About a year later, in fall 2020, TCRWP put out a new position statement, calling for attention to phonemic awareness and phonics instruction, and emphasizing that sounding out words is the best strategy for kids to use to figure out what those words say.

"[P]oring over the work of contemporary reading researchers has led us to believe that aspects of balanced literacy need some ‘rebalancing,’” the document read.

The revised units will offer different guidance on reading “superpowers,” or reading strategies, Calkins said. Instead of being taught “picture power”—to look at the pictures to figure out words—students will be taught “slider power,” that they should “slide” over the word to blend the letter sounds together. Early units will also teach a progression of letter sounds and explicitly address how to decode short, phonetically regular words, Calkins said.

69��ý will still learn “picture power” later, she added, but as a comprehension strategy for understanding the meaning of the story, rather than as a strategy to identify words.

TCRWP will also release new decodable books that include sound-spelling patterns that children learn, so that students can practice applying their phonics knowledge to texts. (Studies have shown that using decodable books can encourage students to try to sound out words while they’re reading.) The group will recommend that teachers integrate these alongside their predictable books, which have repetitive sentence structures and pictures that give clues as to the words on the page. The earliest kindergarten units, which Calkins calls “pre-reading units,” still use predictable books to teach concepts of print and high-frequency words.

Though Calkins says that these changes are “not small,” she also maintains that much of reading workshop will remain the same. “There’s a trademark to our schools that are working with us. There’s a trademark tone to the classrooms. Kids collaborating deeply, passionate about books, talking all the time about their ideas about books, writing up a storm,” she said.

“I don’t think the teachers will find [these changes] jarring,” she continued. ”I think teachers want to learn, and … I can model that it’s OK to say, ‘There were a few things I think I got wrong, and I’m learning about them.’”

Goldenberg, who was one of the researchers who participated in an external review of the Units of Study in 69��ý published in early 2020, said that many of the lessons in the current curriculum are well done, but that they’re “sitting on a flimsy foundation.”

Layering on more attention to the foundations of reading could strengthen the program, but only if this focus is deeply and purposefully embedded, he said.

New teacher guides rethink old practices

Other authors have already released updates into the marketplace, like Burkins and Yates, who have written teacher guides on reading coaching, balanced literacy, and guided reading.

When Hanford’s work first came out, Burkins said, her colleagues in the field were on the defensive—and she and Yates, were, too.

“I’m going to own that I had defensiveness, dismissiveness, uncertainty about why some of these claims seemed outlandish or wrong,” Yates said.

While Burkins had read the work of a few cognitive psychologists in her training, much of the body of research that Hanford drew from was unfamiliar to her. “If you’re an educator, your information inputs have not been from the cognitive [research] side,” she said. Even in her doctoral program, where she completed a dissertation on phonemic awareness research, research courses were limited and she felt that she received mixed messages about evidence-based practice.

Burkins approached Yates about exploring the research together. “Jan really said, ‘Kari, we’ve got to take a deep dive into this because, look—we’ve built careers around supporting early literacy. And we have coached teachers on many of the practices that are being criticized,’” Yates said. “And so I think part of it, for us, was: We know we owe it to the people we’re trying to serve—who are not just children, they’re teachers—to figure out what’s amiss here.”

The book outlines six “shifts” in thinking for the balanced literacy classroom: rethinking how comprehension begins, committing to phonemic awareness instruction, reimagining phonics teaching, revising instruction on high-frequency words, rethinking MSV, and reconsidering which texts beginning readers should read.

The focus, Burkins and Yates said, was on making the research that has appeared in journals accessible and actionable for teachers. They also tried to highlight where practices that many teachers already use align with evidence-based best practice—like engaging students in rich read-alouds, or using text sets of books that approach one topic from different angles to build knowledge.

“When you come in with the approach of, shut all this down and start fresh, you’re going to lose teachers. Energy is our most precious resource,” said Yates. “This work is as much about the reading science as it is about the science of understanding how to support human and organizational change.”

Like Burkins and Yates, Serravallo, the author of The 69��ý Strategies Book, also noted the inaccessibility of paywalled journals. More recently published books, like Seidenberg’s Language at the Speed of Sight, Daniel Willingham’s The 69��ý Mind, and Wolf’s Reader, Come Home “make it easier for people to find the information,” she said.

Serravallo worked with several reading researchers, including Wolf, on the updates to her book. Wolf, who met Serravallo while they were recording a podcast together for Serravallo’s publisher Heinemann, said that they were able to find common ground in a shared vision of what reading instruction should ultimately do.

“She knew that my particular goal, my ultimate goal … is deep reading,” Wolf said. “Deep reading is when the brain has gone well beyond that first decoding brain, and into a place where all the parts are working automatically enough and connected to each other so that time can be allocated to critical thinking, inference, empathy, reflection. All of these are the real goals for a society.”

Strong instruction in foundational skills is just one piece, but a fundamental piece, of achieving that vision, Wolf said.

This work is as much about the reading science as it is about the science of understanding how to support human and organizational change.

Serravallo’s revision is an overhaul of chapter 3 of The 69��ý Strategies Book (the book is designed to help teachers work with students, but it’s not a curriculum). The chapter focuses on strategies for deciphering words. The old version starts, “In order to construct accurate meaning from a text, children need to read words correctly, integrating three sources of information: meaning, syntax, and visual.”

The new version takes an entirely different approach, explaining the different ways a child can decode a word, and noting that the goal of orthographic mapping—"gluing” the spelling and the sound together in memory, so the word can be retrieved automatically.

Gone are the recommendations that children guess at the word based on the pictures or the rest of the sentence; in their place are suggestions for helping students apply their phonics knowledge to word reading. The new version also cites different sources, from a body of research in developmental psychology and cognitive science that wasn’t referenced in the original.

“The common practice that I used, and that my colleagues used, back when I wrote that [original] chapter relied on a certain type of text that scaffolds kids’ early reading by providing a lot of exposure to high-frequency words, some decoding, and some use of meaning to decipher the words on the page,” said Serravallo.

For some children, she said, the combination was enough to get them started on a path to fluent reading. “For other kids, it is a problem,” she said.

69��ý community calls for more work translating research to practice

Seidenberg said the changes in Serravallo’s book, in particular, could prove a useful resource for classroom teachers. But he worries about a framework for reading instruction that is still oriented around “strategies,” focusing on how to respond to struggle.

For example, he said: “If the kid understands that there are digraphs, and has had enough relevant practice with them, you shouldn’t have to have a backup strategy [for recognizing digraphs].”

But Sandra Maddox, a literacy specialist with the South Carolina Department of Education, who consulted Serravallo on the revisions to her book, said that the classroom context isn’t always so predictable. Some students might be able to apply the new phonics skills they learn right away; others need more repetition and targeted reminders. “It’s not enough to just say, ‘sound it out,’” said Maddox, who specializes in working with children with dyslexia.

69��ý researchers, publishers, and educators alike all voiced a need for more translational work—collaborations between cognitive psychologists and educators to implement reading science in ways that are effective and practical.

Understanding reading research is one thing; applying it is another, said Yates. “Knowing how the brain learns to read does not answer the question that a kindergarten teacher [asks], in those 4,000-plus decisions they make every day, about exactly how to proceed with this group of kids in front of them,” she said.

Wolf said that her team at UCLA is “busily building bridges.” They’re working within the school of education, teaching teachers about dyslexia, while also collaborating with neurologists at the University of California San Francisco. “We are really determined to pull neuroscience and education together, for the benefit of all,” she said.

Other researchers, too, are working on local efforts: In Madison, for example, Seidenberg sat on an early literacy task force with leaders from the Madison Metropolitan school district and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Education, with the goal of improving student reading outcomes and closing opportunity gaps.

This kind of work is happening slowly, Wolf said.

It’s hard to know, yet, what effect these publishing changes will have

Maddox has already seen some uptake of Serravallo’s new pages among the teachers she works with. “They’re downloading them, printing them out, and adding them to their book,” she said. “What I hope it does is make teachers more aware of the strategies for decoding, and make them more aware of phonemic awareness and phonics in general.”

This knowledge is more necessary this year than ever, said Blevins, who consults with school districts. Because of educational disruptions during the pandemic, he said, teachers in older elementary grades are seeing large numbers of students with foundational skills gaps—in some cases, for the first time.

“They don’t even know where to start. [The teachers have] never heard of blending,” he said. He’s started doing sessions with 3rd, 4th, and 5th grade teachers in addition to the earlier elementary teachers he normally works with, teaching them a handful of key routines they can use and introducing them to a comprehensive phonics survey they can give kids to figure out what skills they need to focus on.

“I think that there’s a recognition that upper grade teachers need more knowledge of phonics,” said Calkins. “Third graders, the last time they had an uninterrupted year in school was kindergarten.”

But researchers say there are still barriers in schools to identifying student needs. “I do think the measurement groups have been slower to respond than some of the instructional ones,” Matthew Burns, a professor of special education in the University of Missouri’s College of Education and Human Development, said of common classroom tools used to take reading inventories, evaluating what students know and don’t know.

In a study on publisher Fountas and Pinnell’s reading inventory, Burns and his colleagues found that the results weren’t reliable: 69��ý would receive different scores with different books that were supposedly both at their reading level. “We put too much stock in the score we get from these measures,” he said.

Fountas and Pinnell materials, which include reading curricula as well as assessment tools, use many of the word-guessing strategies that other publishers are starting to move away from. The group’s founders, Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell, declined to comment for this story through their publisher, Heinemann.

However, in a Sept. 8 opinion piece for Education Week, Fountas and Pinnell distanced themselves from the term “balanced literacy,” and characterized the ongoing conversation about reading practice as the “latest chapter in the reading wars.”

“We believe this round of conflict, like the previous ones, is harmful to our profession and has real potential for confusing children as well as teachers and administrators,” they wrote.

Fountas and Pinnell’s intervention materials, Leveled Literacy Intervention, hold a large share of the market—43 percent of early elementary and special education teachers said they used LLI in a 2019 EdWeek Research Center survey.

Changes to materials would better support teachers, Blevins said. But he stressed that stamping a “science of reading” approved seal on a resource and putting it in teachers’ hands doesn’t necessarily give teachers the knowledge and understanding they need to change their instruction.

“Whenever you see these shifts happening, it’s always surface knowledge,” Blevins said. “What that has boiled down to is … on social media, teachers will name a program and say, ‘Is this science of reading?’”

The overwhelming interest in reading research presents an opportunity, and a caution, Blevins said. “It is a moment that if we did it right, we could take advantage of it and help millions of kids. But we need to go deeper.”