Michael Randolph, the principal of Leesburg High School in Lake County, Fla., had a wide grin on his face in all the pictures of him handing out diplomas to the graduating class. After all, it’s taken seven years of hard work to get here.

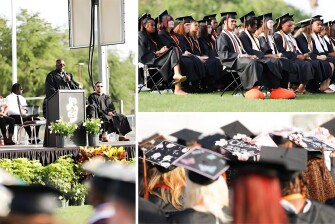

The graduation, held in mid-May, was a historic one for the school—the highest number of seniors were graduating in its 98-year-old history. In Randolph’s seven years as principal of Leesburg, the graduation rate has climbed from 67 percent to 88.9 percent, comparable to other schools in Lake County, and better than the state’s average of .

When Randolph first took over the helm, though, this milestone might have seemed like a stretch.

“We were being looked at [by the district] as a takeover school,” he said. “We had major perception issues. But to be honest, we had earned them.”

When Randolph came on board in 2017, the school had close to 3,000 disciplinary referrals, and the school was known for fights and drug use on campus, not for its academics. Chronic absenteeism rates hovered around 45 percent for Leesburg’s white students, about 28 percent for its Black students, and nearly 17 percent for Hispanic students. (Chronic absenteeism is broadly defined as missing 10 percent or more of school days, for excused and unexcused reasons.)

Eighty percent of the about 1,775 students at the school are identified as “economically disadvantaged” by the Florida Department of Education. Several Leesburg students are the primary earners in their families, said Randolph, and they have to make a choice between working or coming to school.

Randolph knew he had to tackle the negative perception about Leesburg as he simultaneously attacked the twin issues of a low graduation rate and high levels of chronic absenteeism. What followed was a concentrated effort to shift the school’s narrative through an uplifting social media campaign that Randolph dubbed “#180daysofjoy.” Since 2017, Randolph has posted positive updates about Leesburg every weekday on the school’s official Instagram page without pause.

The online campaign documented the structural changes that Randolph and his team were making within the school to give every student a workable pathway toward graduation.

The school has built a multi-pronged model—outfitted with options for night and online school for credit recovery—to give as many options as possible to students. These efforts have contributed toward a 20 percent increase in the school’s graduation rate, as well as a 20 percent increase in enrollment over the last seven years.

To improve the graduation rates, Randolph realized he had to think differently about attendance.

“As a school, we had to accept that there are circumstances that don’t allow our students to come to school,” he said. “But that shouldn’t impact their ability to learn. We had to learn to be flexible.”

Different pathways are a mitigation strategy

In 2017, the school received funding from the Lake County district to hire a graduation resource officer, who developed a graduation tracker for every student to keep track of the credits needed to graduate. Audits happen every quarter.

The effort started with the 300 seniors; it’s now expanded to all students, right from the time they enter the high school. The tracker is also an effective way for the school to keep track of attendance issues, Randolph said.

There is a direct relationship between improved attendance and graduation rates, said Robert Balfanz, the director of the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, whose research addresses solutions to chronic absenteeism in schools. “69��ý who are chronically absent either don’t know the material well enough to pass a course, or they don’t turn in the required assignments. Failing classes has a clear line to dropping out, or not graduating.”

Providing students with alternative pathways can potentially “mitigate” the impacts of chronic absenteeism on graduation rates, Balfanz said.

At Leesburg, students can go to night school or achieve required credits through online self-study. 69��ý who work full-time often choose to go to night school, an option that the school started in 2022. Other students who choose this option might be caring for younger siblings during the day, said Randolph.

At night school, students get assistance from educators as they work on their assignments.

The school created its online study option after noticing that students who were typically absent were still able to complete their work online during the pandemic, Randolph said.

It was also a way to address the needs of students who faced disciplinary problems in school and were at risk for suspension.

Disciplinary action, Balfanz said, can contribute to absenteeism. 69��ý are often handed multi-day suspensions, which can mean missing close to a week of school.

“Kids also know when fights are brewing [in school],” he said. “They may want to stay away from the drama.”

Randolph admitted that in his first three years as principal, he was suspending students frequently, which helped neither the morale of the school nor its graduation rates. Providing an alternative pathway to students has helped curb the suspension rate, he said.

69��ý who choose to study online can do so remotely, but the administration at Leesburg has incentivized them to complete their studies on campus by creating a “school within a school.”

The online school within the physical one has its own bell schedule, and students usually move between one or two classrooms that are monitored by teachers. These classrooms even have their own snack counter.

The online learning option comes with requirements, though: 69��ý have to complete 20 assignments per day to be marked present for that day. Leesburg started this policy of “positive attendance” in 2023.

“We’ve had success with this model because students, learning through their Chromebooks, can knock out four to five credits per semester,” said Monique Griffin-Gay, an assistant principal at Leesburg and one of the key architects of the online school model.

Randolph said 170 students, or 10 percent of the total student body, chose alternative learning pathways in the 2023-24 academic year.

“In the past, we didn’t have a way to work with these [chronically absent] students,” Randolph said. “They may have dropped out or been asked to leave.”

The alternative pathways also allow older students, who may enter 9th grade at age 16, to graduate high school early.

Parents as partners

One of the key partners in Leesburg’s gradual turnaround has been parents. These parents have a history with the school—many of them attended Leesburg and carried the same negative perception that Randolph’s been trying to change.

“It was very much the school versus parents in 2017,” he said.

Bringing parents onboard to address the twin challenges of absenteeism and academics was critical.

Randolph started connecting parents to the graduation resource officer early on to figure what was holding back students from attending school or getting the required credits toward graduation. These conversations would help the administration to determine the right graduation pathway for a student.

Parents have also participated in “restorative conversations” around disciplinary issues, Randolph said, which has allowed Leesburg to bring down its days of suspension from 300 in 2017, to less than 200 last year. Disciplinary referrals, too, have gone from 3,000 to 400 during the same period. Parents have played a key role in creating a better school environment, administrators said.

This doesn’t mean that the 700-odd conversations Randolph and his team have with parents every year are easy. One such conversation revolved around assigning grade-level texts to students. Parents complained to the school that the work was too hard for students. Randolph pushed back.

“We had to educate our parents about grade-appropriate texts and assessments and tell them that students must meet these requirements to graduate,” he said. “That was a shift for some of our parents.”

A work in progress

Over the last seven years, the administration at Leesburg has worked on repairing their relationship with students, their parents, and the surrounding community. The consistent social media presence has helped, Randolph said.

The changes in the school have positively impacted teachers, too. Randolph said the school will retain 90 percent of its 88 teachers for the upcoming school year. When Randolph first came on board, he had 37 vacancies to fill.

Still, there’s more work to be done. In the 2022-23 school year, more than 45 percent of students at Leesburg well below grade level in math; for English/language arts, the figure was 31 percent.

And chronic absenteeism rates, despite all efforts, remain stubborn: In the 2022-23 school year, 35.5 percent of white students, 32 percent of Black students, and 24 percent of Hispanic students were considered chronically absent.

The new school year will also bring a fresh challenge. About 73 percent of next year’s high school seniors are already graduation-ready, which means they’ve taken the necessary assessments in math and reading that are required to graduate. This is a step up from the usual 40 to 50 percent of incoming seniors who’d be ready to graduate in previous years.

This has increased the pressure on Randolph and his team to make sure that these students are leaving with the skills—and credits—they need to attend college, start a career, or join the military.

“These kids are going to have a much shorter runway,” Randolph said.

Randolph’s next goal is to get to a 90 percent graduation rate, a milestone that didn’t seem possible to him the year he joined as principal. He also hopes that policies like “positive attendance” can curb the chronic absenteeism numbers for Leesburg.

“The trickiest bit of this work is to figure out what’s going to motivate students,” said Griffin-Gay. “You can put 50 options in front of them, but they don’t matter if students don’t see the point in graduating. We have to keep instilling the belief that they can do this.”