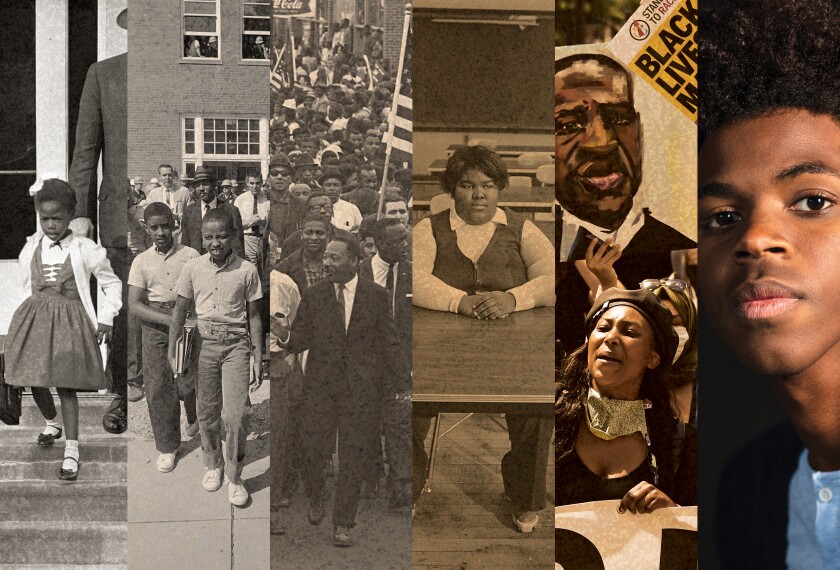

Black History Month is a time for celebration of Blackness; 28 days of joy, love, and stories of miraculous inventions, speeches that shook the moral compass of millions of people, movements for justice that raised the world’s consciousness, and the acknowledgement of a collective human spirit so set on freedom it keeps on pushing for and teaching this country what democracy truly is every day. But when schools reflect America’s racism and the rejection of racial progress, how are students supposed to understand Black history beyond the pages of a book?

This month is more than just a series of lessons focused on how Black people fought for justice in this country: It is a month of wrestling with contradictions while celebrating triumph. A month of textbooks, bulletin boards, and presentations where all children, but especially Black children, learn about movements for racial justice; however, they typically will not see that justice reflected in their schools.

Black students will learn about the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education and how Black families fought to integrate schools as they currently sit in crumbling, . This month Black students will watch video after video of Black people being beaten by the police in the 1950s and ‘60s in their fight for racial justice, as many walk through their schools under the surveillance of the police. that having police in schools or on campus is linked to a disproportionate number of Black and brown students being arrested, expelled, and suspended. Over the last several years, we have watched videos of school police officers physically assaulting Black students, especially Black girls, as they are beaten by the very people paid to protect them. How can a Black student make sense of a lesson that shows racism as historical artifact when they also see a social media feed filled with videos showing the same violence today?

Black students are going to learn how Black people fought for protection from employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, Black teachers today are scarce. After Brown v. Board of Education, Black educators were given the pink slip. According to research by Professor Leslie Fenwick, prior to Brown in the 17 states with segregated school systems, Black teachers and principals made up 35 to 50 percent of the educational workforce. Almost 70 years later, the percentage of Black teachers has plummeted to a mere 7 percent nationally, while only 11 percent of principals are Black. Black teachers were systematically removed from the profession by expensive and irrelevant teacher licensure exams and school board requirements that ensured the erasure of Black educators. How can a Black student explain a positive impact from the Civil Rights Act on employment when they see few, if any, educators who look like them in their school?

If Black history is to matter in the very place we know it’s going to be taught, then schools must reflect Black history, not just teach it.

Black students will sit in segregated schools, surrounded by police, taught largely by white educators, learning that America’s racism of the past is just that—history—when it is ever present.

Not to mention that Republican lawmakers throughout the country have, with surgical precision, passed legislation that bans the teaching of America’s racial history and Black history. Making national news, rejected an Advanced Placement African American Studies course. The state said the course “significantly .”

A 2022 by the RAND Corp. polled nearly 2,400 K-12 teachers and about 1,500 principals and found that 1 in 4 teachers were told by school officials or district leaders to limit conversation about race and racism in their classrooms. When teachers don’t talk about race and racism in the classroom, they are still teaching about race and racism. The absence of conversation speaks loudly, telling students what histories, people, and contributions matter, and, ultimately, who belongs in society.

If Black history is to matter in the very place we know it’s going to be taught, then schools must reflect Black history, not just teach it. We don’t need schools that just teach Black history; we need schools that reflect the sacrifices of those who fought to integrate schools, protested to end police brutality, and worked tirelessly to ensure Black educators were front and center, inspiring Black students.

There is so much beauty, kindness, love, grace, and intellect packed into these 28 days of Blackness, and I am grateful to my amazing teachers who taught me that at an early age. But my teachers also instilled in me the courage to pick up where my ancestors left off, because the struggle for racial justice in this country has no end date.