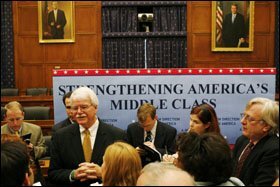

When a reporter asked Rep. George Miller last week whether his agenda for early-childhood education would involve expanding Head Start or starting a universal preschool program, he had a simple answer.

“Both,” the California Democrat said, a smile curling from under his gray mustache for one of the few times during the 45-minute news conference.

“I’m an ambitious guy,” he added, almost under his breath.

And when the Democrats become the majority in the House of Representatives next month for the first time in 12 years, Rep. Miller will be in charge of an ambitious agenda.

Read the related story,

As the chairman of the Education and the Workforce Committee, he’ll spearhead efforts to restructure student-aid programs, overhaul the Head Start preschool program and possibly begin a federal effort for universal prekindergarten, and reauthorize the No Child Left Behind Act. He also said he’ll hold oversight hearings on how the Bush administration has managed the federal 69��ý First program and other initiatives.

That’s just in education. In labor policy, the other chunk of the committee’s domain, Mr. Miller will be expected to help deliver on the Democrats’ promise to increase the minimum wage and protect workers’ pensions, as well as investigations into of workplace safety.

He says the wide-ranging list adds up to a “simple, but urgent” mission to strengthen the earning power of middle-income America.

“This is a very real issue,” Mr. Miller said at the Dec. 12 news conference. “The middle class is losing ground.”

Family Business

At the age of 61, George Miller III is about to enter his 33rd year in the House. He was born into Democratic politics as the son of the late George Miller Jr., an influential California state senator.

“People used to come to our house with all sorts of problems,” Rep. Miller said in an interview last week. “To grow up and see somebody be able to help your neighbors is pretty rewarding.”

By age 29, in 1974, Mr. Miller had won his first election to represent the industrial and suburban communities east of the San Francisco Bay in Congress. Although many new Democrats who won election that year took advantage of anti-Republican sentiment in the aftermath of Watergate, Mr. Miller captured a reliably Democratic district that shares his liberal philosophy.

The 7th District’s oil refineries, steel mill, and other industrial factories bring a “union heritage” with a natural link to Democrats, says Bruce E. Cain, the director of the Institute for Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. As the demographics of the cities of Richmond and Martinez and surrounding Contra Costa County have diversified, the Democratic majority in the district has grown solidified, Mr. Cain adds.

Today, 40 percent of the population is Latino or black, and 16 percent is of Asian descent.

“It’s a pretty liberal district,” Mr. Cain said. “It reflects [Mr. Miller’s] policies in many ways.”

Throughout his congressional career, Mr. Miller has been a strong voice supporting traditional Democratic Party issues, including the expansion of federal education policies.

Early in his tenure, when Democrats held an entrenched majority in the House, he sponsored laws that reformed foster care, protected the California desert, and dealt with other social and environmental concerns.

Age: 61

Hometown: Martinez, Calif.

Family:

Married to Cynthia Caccavo Miller for 42 years; father of George IV and Stephen; five grandchildren ages 1 to 12

Education:

• Law degree, University of California, Davis, 1972

• Bachelor’s degree in American Studies, San Francisco State University, 1968

• Associate’s degree, Diablo Valley Community College, 1966

Congressional experience:

• First elected in 1974

• Ranking Democrat on the House Education and the Workforce Committee since 2001 and a member of the committee since 1975

• Chairman, House Democratic Policy Committee, 2003-present

• Chairman of House Resources Committee, 1992-1994; ranking Democrat on that panel, 1995-1999

Other political experience:

• Staff member, state Sen. George Moscone, a Democrat, who was majority leader of the California Senate, 1969-1974

Hobbies:

69��ý, backpacking, skiing

SOURCE: Education Week

After the GOP triumph in the 1994 midterm elections, when the newly empowered majority worked to scale back Democratic accomplishments such as federally subsidized school meals and the Title I program for disadvantaged children, he became known for his fiery speeches in committee hearings and on the House floor. Once, Rep. Miller spoke so loudly that the Republican sitting in the House speaker’s chair broke the gavel trying to get his attention after he went past his allotted time.

In 2003, Rep. Nancy Pelosi, who represents a San Francisco district across the bay from Rep. Miller’s, became the House Democratic leader, and she appointed him chairman of the House Democratic Policy Committee. That panel outlined much of the agenda that served as the Democrats’ platform in this fall’s elections.

In an e-mailed statement to Education Week, Rep. Pelosi, who is set to become the speaker of the House in January, called Rep. Miller “her dear friend” and said he “is tireless, dogged, and relentless in his efforts to try to expand opportunity through education.” When President Bush came to office in 2001, the 6-foot, 4-inch Mr. Miller befriended him to the point of earning one of the president’s distinctive nicknames: “Big George.”

That cordiality helped foster a working partnership in which Rep. Miller, along with Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, D-Mass., helped craft and gather support for the No Child Left Behind law, one of Mr. Bush’s top domestic priorities. Signed into law by the president in January 2002, the measure reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and dramatically changed its central program, Title I, to require that schools demonstrate gains in student achievement.

Highly Qualified Teachers

In the interview last week, Rep. Miller said he supported the law because it includes accountability measures requiring districts and schools to prove students are learning. That’s something he had pushed for in 1999 in Congress’ failed previous attempt to reauthorize the ESEA.

Before the NCLB law, “there was no real accountability,” he said. “There were no real standards that people couldn’t fudge and doctor up all of the time.”

He also persuaded lawmakers to insert a requirement that districts guarantee all of their teachers meet their states’ definition of highly qualified.

While Rep. Miller’s support for the law surprised many Washington lobbyists, it reflected two of the congressman’s priorities, said Bruce Hunter, the senior lobbyist for the American Association of School Administrators. It set out to improve opportunities for low-income students, something Mr. Miller had always put at the top of his agenda, and it set up a new approach for reaching that goal.

“He’s always pushed: ‘Let’s try this. Let’s try that,’ ” said Mr. Hunter, whose Arlington, Va.-based group has been critical of the law’s prescriptive nature.

Republicans say that they like working with Rep. Miller because he’s willing to take unorthodox positions on issues such as accountability that challenge traditionally Democratic interest groups, including teachers’ unions, to improve the quality of services they provide students.

Rep. Howard P. “Buck” McKeon, R-Calif., the education committee’s outgoing chairman, said in a statement he expects that the panel would continue to work across party lines on many education issues.

Rep. Miller’s support for the legislation also shows that he’s willing to take positions that have the potential for improving schools, said Amy Wilkins, the vice president of governmental affairs and communications for the Education Trust.

“He’s thought so long and so carefully about these issues,” said Ms. Wilkins, whose Washington-based research and advocacy group supports the law’s accountability measures. “At the same time, he remains open to hear other members’ concerns and bring them along.”

Although the NCLB law is unpopular among many educators, Rep. Miller said the leaders of the school districts he represents see the value in its focus on ensuring all students are receiving the instruction they need to eventually become proficient in reading and mathematics.

“The assessment process before No Child Left Behind was a political tool,” he said in the interview. “Now it’s an educational tool.”

Rep. Miller acknowledges, though, that the 5-year-old law needs some changes, including changing accountability rules to reward schools for growth of student achievement.

“I’m open to change and understand what it’s like on the front lines,” he said.

Rep. Miller promises to shepherd a bill through the House next year to reauthorize the federal law—something the Bush administration is also promoting.

While that would keep to the schedule set when Congress passed the law in 2001, many in Washington say the goal is another reflection of Rep. Miller’s ambition. Given a Capitol Hill agenda packed with other issues, they say, and the NCLB law’s complex and controversial provisions, Congress will be hard-pressed to adopt a bill by the 2007 deadline.

“It’s a very, very high priority,” Rep. Miller said at the news conference. “It’s a very, very important piece of legislation in terms … of raising standards.”