When the gender gap in STEM education is discussed, it usually centers on the lower proportion of women pursuing college majors and careers in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math.

But some recent data suggest STEM achievement disparities persist at the K-12 level, based on results from the Advanced Placement program as well as national and global exams.

And yet, what may be true for the United States is not necessarily so around the world. In some instances, international averages on global exams tell a different story, with either no measurable gender difference in math and science scores or girls outpacing boys.

How to interpret the U.S. data is a conundrum, some experts say.

“This is a bit of an unexplained phenomenon,” said Martin Storksdieck, the director of the National Research Council’s Board on Science Education. “My sense is that these differences are potentially a question of the kinds of tests we have, and the kinds of self-confidence people have, and expectations they have, rather than an innate difference or potentially stronger preparation that boys may have over girls.”

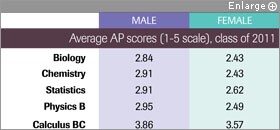

A variety of data indicate a gender gap in science and math achievement, with girls trailing boys.

SOURCES: College Board; Education Week

The gender achievement gaps are far smaller than those seen for low-income, black, and Hispanic students. But they are evident across a number of measures.

Take the AP program. In all 10 STEM subjects currently taught and tested, including chemistry, physics, calculus, and computer science, the average scores of females lagged behind males, according to data for the class of 2011.

Trevor Packer, the senior vice president of AP and college readiness at the College Board, said his New York City-based organization is concerned about the data.

“It’s significant whenever you see different populations, ... whether different by region or gender or ethnicity, perform at different levels,” he said.

Against the Global Grain?

In fact, the College Board recently commissioned a study to examine one possible factor, known as “stereotype threat.” This anxiety is believed to occur when individuals in a certain population group, such as racial and ethnic minorities or females, face a situation in which they may be judged by a negative stereotype. Some research suggests that can diminish performance on assessments, especially high-stakes tests.

Recent results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress indicate some gender gaps, mainly in science.

The latest , for 2011, show 8th grade boys outscoring girls by 5 points on NAEP’s 0-300 scale for the subject. Only 8th graders were tested that year. Looked at another way, 37 percent of boys scored “proficient” or above, compared with 29 percent of females.

show average scores for girls trailed boys at all three grade levels tested. The NAEP gap widened for older students, from 2 points at 4th grade to 4 points at 8th grade and 6 points at 12th.

Going back to 1996, NAEP data show a fairly consistent pattern of girls trailing boys, though the gap size has varied.

In math, show boys performing only slightly better on average, with a difference of just 1 point at the 4th and 8th grades on the 0-500 scale. (The difference was statistically significant.)

In looking beyond the U.S. border, the issue of STEM achievement by gender gets more complex.

Boys—on average—outperformed girls in math across the 34-member nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, based on the , in 2009, from the Program for International Student Assessment. PISA gauges 15-year-olds. In science, there was no measurable gender gap on average across the OECD nations.

PISA results for American students show lower average scores for girls than boys in math and science. In fact, the U.S. gaps were among the largest of any countries tested, an OECD report says.

In science, the biggest gaps favoring boys were in the United States and Denmark. Girls outscored boys in Finland, Greece, Poland, Slovenia, and Turkey.

Data from another global assessment suggest girls generally enjoy an achievement edge in math and science when averaging results across the 58 participating nations and jurisdictions, but not in the United States. That outcome is for the latest round, in 2007, of the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study.

In science, the global TIMSS average was higher for girls than boys at the 4th and 8th grades, according to an analysis by Boston College. By contrast, U.S. boys scored higher than girls at the 8th grade. At the 4th grade, U.S. boys scored higher, but the gender gap was not statistically significant.

For math, the global average for girls was higher at the 8th grade, but for U.S. students, the gender gap was not statistically significant. At the 4th grade, there was no statistical difference in the global average by gender, but American boys outscored girls on TIMSS.

The global data seem to cast doubt on the notion that innate differences between males and females help explain the U.S. situation.

A 2007 report from the National Academies plays down the significance of innate gender differences, as well as differences on achievement tests, in affecting females’ ability to excel in the STEM fields.

“Research shows that the measured cognitive and performance differences between men and women are small and in many cases nonexistent,” it says. “Furthermore, measurements of mathematics- and science-related skills are strongly affected by cultural factors.”

Higher GPAs

Andresse St. Rose, a senior researcher at the Washington-based American Association of University Women, says not all K-12 STEM data point in the same direction.

“Girls actually take slightly more math and science credits than boys do, on average,” she said, “and they actually earn slightly higher grade point averages, but when you get to the AP exams, for example, you see the boys doing a little better.”

She still sees reason for concern and believes stereotype threat may be an important issue.

“All of us really need to examine our thinking and our beliefs and our behavior around different genders,” she said. “Do we really encourage girls to do all the things that boys are encouraged to do?”