The current movement for paying teachers based on how well they teach, rather than how long they’ve been on the job, represents at least the fourth wave of national interest in performance-pay plans, two scholars say in a new book.

With some deliberate planning, comprehensiveness, and attention to what drives teachers to enter the field, the Harvard Graduate School of Education researchers contend, recent efforts to reshape teacher-pay systems might not be as short-lived as they were in the past.

Susan Moore Johnson and John P. Papay make that case in , being published this month by the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-oriented Washington think tank. Ms. Johnson and Mr. Papay trace the origins of teacher merit-pay programs to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and offer a new model that builds on the successes and failures of past efforts.

“I really think we have to rethink the current salary schedule and not add to it little pieces of incentives that will direct teachers in the wrong way,” said Ms. Johnson, a professor of teaching and learning and the director of Harvard’s Project on the Next Generation of Teachers. Mr. Papay is an advanced doctoral student and a research assistant on that project.

The book, which was presented at a conference last week at the institute, has already drawn some favorable responses, including one from the American Federation of Teachers, which often looks cautiously on such efforts. In a press release, AFT President Randi Weingarten said the book “takes serious steps toward not just demonstrating what is wrong with current teacher-compensation systems but also offering good, solid ideas on how to fix it.”

From 1880s to Now

The authors say early efforts to peg teachers’ salary increases to administrators’ assessments of their effectiveness grew out of the “scientific management” theories developed by Frederick W. Taylor in the 1880s and 1890s.

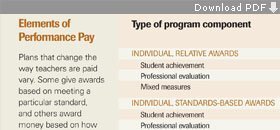

Plans that change the way teachers are paid vary. Some give awards based on meeting a particular standards and others award money based on how individuals or groups compare.

SOURCE: Redesigning Teacher Pay

Often abused, such systems disappeared quickly, and were replaced by the single-salary schedules used in most districts today. Interest in merit pay surged again briefly in the 1960s, the book says, in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik, and in the 1980s, following the publication of the education critique A Nation at Risk.

“We’re returning to that approach again with new methodology,” Ms. Johnson said, “but we still haven’t figured out how to assess teachers’ work in all its complexity.”

Beginning in 2006, with support from President George W. Bush, the federal government set aside $100 million to launch the Teacher Incentive Fund, a grant program aimed at encouraging experimentation with performance pay. Under President Barack Obama, the U.S. Department of Education has continued to bolster that program.

“It’s time to start rewarding good teachers,” Mr. Obama is quoted as saying in the book, “[and] stop making excuses for bad ones.”

Proposed guidelines for the $4 billion Race to the Top program, part of the economic-stimulus law, go one step further and require states to allow districts to use students’ test scores in making decisions about teacher compensation and evalution if they want to land a federal grant from the competition.

To take a closer look at the merit-pay programs under way, the Harvard authors studied compensation systems devised by districts in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C.; Hillsborough County, Fla.; Houston; and Minneapolis, all of which take a slightly different and complex approach to the task.

“One thing that was clear is that these programs developed over time, and in response to a variety of opportunities, so it wasn’t necessarily a planful approach,” Ms. Johnson said. “I think the bigger question, though, is whether the pay system is actually helping districts increase the capacity of schools to educate students, or whether they are just satisfying the external expectation that the pay system ought to help teachers work harder.”

Often, she added, districts don’t ask expert teachers to share their know-how, and don’t target incentives to address gaps in skills or staffing or to support teachers’ career aspirations.

Some districts also run into problems, the researchers found, when teachers begin to doubt the accuracy of the measures the systems use to judge their effectiveness—regardless of whether those evaluations were done by principals on a “drive by” classroom visit or by statistical analyses of students’ test-score gains.

For example, in Houston, where school officials are basing rewards on student test scores, some teachers have come to regard the district’s pay system as a “lottery,” because they don’t know what they have to do to achieve a bonus, according to the book.

New Roles, New Pay

The system that Ms. Johnson and Mr. Papay propose is reminiscent of the career-ladder systems of the 1980s and the Teacher Advancement Program, begun by businessman Lowell Milken, which dozens of districts use today.

Their proposal would set up four tiers to classify teachers’ pay gradations, based on their expertise, effectiveness, and the roles they take on outside the classroom. Beginning teachers would make up the first tier, remaining there until either passing a tenure review or being let go. Most tenured classroom teachers would occupy the second rung of the salary schedule.

In the third tier, teachers would be expected to open their classrooms so that less-skilled teachers could observe them, or take on other kinds of leadership roles.

The highly effective teachers who made it to the fourth tier might assume even greater leadership roles, serving full or part time, for example, as coaches, data analysts, or peer evaluators.

The plan also calls for supplementing the tier system with performance bonuses for schools whose students made above-average learning gains, and for other incentives aimed at addressing staffing shortages or drawing top-notch teachers to struggling schools.

Ms. Johnson said the most novel feature of the authors’ plan, though, is its recommendation for a “learning and development fund,” created from money previously used to reward teachers for accumulating academic coursework and degrees. The fund would finance learning opportunities that were more targeted to the changing needs of the district or to building needed skills.

“This is much more comprehensive than anything I had seen in the past,” said Robert R. Spillane, a former superintendent who spearheaded a now-defunct career-ladder plan used for seven years in the Fairfax County, Va., public schools. But, he added, the “devil is in the details,” most of which the researchers would leave up to local school systems to decide.

One such detail: how to evaluate teachers. While such systems should take into account student achievement, the researchers say, they caution against relying solely on “value added” measurements, which account for students’ year-to-year learning growth rather than overall achievement. In practice, the authors say, such measurements fluctuate too much from year to year, require testing in every grade, and exceed the capacity of most districts to carry them out.

The potential cost of a system that pays for new learning opportunities at the same time that it rewards teachers is another unanswered question.

Thomas Toch, the executive director of the Association of Independent 69´«Ă˝ of Greater Washington and a longtime education analyst, said the proposed system’s benefits in the end might outweigh any added costs.

“More-comprehensive models cost money,” he said, “but we currently spend over $16 billion a year on professional development that is not tied to teachers’ strengths and weaknesses, and not nearly as deliberate as it needs to be.”