The Montessori and Direct Instruction teaching methods can seem worlds apart. But in Texas' Aldine district, parents can pick between them—at the same schools.

Candee Wilson commands two universes in one school building. “The part to the right is Montessori World,” the principal explains, nodding toward one wing of the A.B. Anderson Academy. There, the classrooms are run according to the perennially avant-garde thinking of the Italian physician and educator Maria Montessori.

“And here,” she continues, “is DI World,” where another set of teachers practices the Direct Instruction methods of skill-building dear to many academic traditionalists.

The two worlds often collide when ideologues battle over how best to teach children. But here in this public magnet school on the frayed northern edge of Houston they coexist harmoniously. The students from the Montessori classrooms and those from the Direct Instruction classrooms literally make music together. Fine arts offerings are the third major draw of the school, which serves 1st, 2nd, and 3rd graders in the Aldine Independent School District.

As far as Wilson and other officials in the 53,000-student district know, Anderson’s program and the almost identical one at its nearby “sister” school for prekindergarten and kindergarten, the Versa V. Reece Academy, don’t have a match elsewhere in the nation. Not in wealthy suburbs, let alone in a district where 79 percent of the children are poor or near-poor, and where 8 percent are non-Hispanic whites.

“Curious and kind of surprised” is how educators from outside Aldine often react to the notion of a school housing such contrasting approaches to learning, says Wilson, a pert woman with poise galore.

But there is another surprise: “They usually don’t realize that parents have chosen their child’s program.”

Anybody visiting Anderson Academy— and many do—should not be in a hurry.

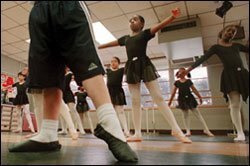

Visitors will want to pause at the door of the dance studio and steal a glance. On a recent day, 18 diminutive performers in leotards and pink slippers step-slide the length of the wooden floor under a mirrored disco ball. Michelle Schroeder, who not long ago was named “Texas K-2 Dance Instructor of the Year,” oversees their progress.

Down the hall, Anderson’s full-time art teacher discusses perspective with his charges, while across from the art room, one of the academy’s two full-time string teachers leads a handful of 2nd and 3rd graders playing pint-sized violins in a spirited “Go Tell Aunt Rhody.”

|

Boys and girls warm up prior to Michelle Schroeder’s dance class at A.B. Anderson Academy. The fine arts magnet school in North Houston soon will be holding its spring recital, an annual showcase of student talent. |

Children at Anderson and Reece rotate every afternoon among music, art, and drama. At Anderson and most years at Reece, some students also take violin, viola, or cello on school instruments that go home for practice. Others choose a dance class that covers ballet, tap, and jazz.

Summer school helps students stay in tune during June and July, especially for the children in the dance and string performance groups.

“We are encouraging the children to have real standards for performance,” says Assistant Principal Julie Johnson over the controlled din of Anderson’s standard-issue cafeteria. The two schools’ leaders believe that the fine arts, taken seriously and taught with the district’s academic goals in mind, will help children master not only rhythm and color, but also the three R’s. “Fine arts and academics are interlocking here,” Johnson says, lacing her fingers together.

But when she pulls them apart again, the two hands could represent the academic halves: Direct Instruction and Montessori.

Take, for instance, Laura Perez’s Montessori class at Reece Academy. Compare it with LaTonya Miller’s Direct Instruction kindergarten perhaps 20 steps away.

In the Montessori classroom, a New Age composition, turned down low, mellows the air. Teacher Perez kneels by the side of a child, listening, then speaking in a near- whisper. When she or her assistant minister to one of their 3- to 5-year-olds, they seem to demand nothing from the child. In fact, the “demands” are around the children’s necks on cords. “Daily Work Card” says the laminated paper with a list of subjects, some in the special lingo of Montessori: “language,” “math,” “golden beads,” “sensorial,” “practical life.”

The 23 children, 3 to 6 years old, move from activity to activity as their cards direct, each activity geared to a specific skill or understanding. Once students have demonstrated mastery—to a teacher or a more advanced peer—they can check off the subject for that day.

In Montessori education, a classroom is a “prepared environment” for fostering growth, filled with many of the special hands-on materials that have been in use since the Italian education pioneer’s work in the early- and mid-20th century. Children learn at their own pace from all five senses.

Keara, who on this March day says she is “3, 4 in April,” bends over a diagram called an “addition wheel.” She has placed it on the square of carpet that marks her work space. Along with the diagram are red beads for counting and red foam squares with the numerals 1 through 7 on them. The task is to formulate and solve one-digit addition problems from the numbers in two concentric circles of the wheel. She can use any of the materials to help her, but she quickly sees the first answer and gripping her pencil, writes in wobbly numerals the equation 1 + 1.

Sitting cross-legged next to her, Marlon, 4 years old, sounds out the endings of words. “D-uh-l,” he says looking at a picture of a doll and flipping his hand over as he enunciates each different sound.

“What subject do you like to do the best?” a visitor asks.

“Free choice,” says Marlon firmly, referring to the Montessori practice of giving children a break with a regular school activity of their choice. Then he goes back to his words.

Across the way, in LaTonya Miller’s Direct Instruction kindergarten, free choice is not a given, the teacher is at center stage, and even the sounds are different. The Montessori classroom hums. The Direct Instruction classroom moves forward on percussive rhythms: a call, a response, a snap of the teacher’s fingers.

“Go to the blue carpet,” Miller directs, calling six children by name. They gather in six little blue chairs facing their teacher, one of six groups that Miller and her aide have formed according to reading skills.

The young teacher asks in a clear voice ringing with energy: “Are you rea-dy?”

“Yes, ma’am,” comes the response, almost a shout.

|

Nigel Maddox, 8, manipulates a large bead frame in Traci Fisher’s Montessori classroom at Anderson Academy. The school’s approximately 600 students are split almost evenly between its Montessori and Direct Instruction programs. |

“When I touch it, you say it,” Miller continues, holding high the inside of a spiral-bound book. The book is part of the SRA’s Direct Instruction programs, published by McGraw-Hill Cos., which grew out of the work begun by maverick researcher Siegfried Englemann in the 1960s. The approach emphasizes careful and explicit skill-building and, in reading, phonics. It lays out in detail what teachers should say and do in lessons.

With an exaggerated gesture, Miller puts her finger on letter after letter in the book, some of them with shape or notation cues to differentiate sounds. The kindergartners chorus back the sounds.

“Good job! Now, say these words the fast way,” Miller continues, calling for the children not to sound out the word phoneme by phoneme but to state it whole. She points to a word.

“Like” they respond. She points again. “Liked.”

After that warm-up, Miller asks individual pupils to read sentences in a story.

“Part of the program is to make sure they stay focused,” the teacher says later. “Lessons must completely flow.”

Except for the fine arts and physical education instructors, teachers at Anderson and Reece are hired specifically for the Montessori or Direct Instruction classrooms. Most of the teachers, though, don’t come with the training they need. Direct Instruction teachers get a week’s workshop in the method and then periodic help during the year.

And although a few teachers have been hired already certified in Montessori, most have received eight weeks of training from the Houston Montessori Center during the summer, at a cost to the district of at least $4,200 per teacher. As they head classrooms, the Montessori trainees—already certified teachers—fulfill a two-year Montessori internship requirement that includes scrutiny of their teaching and workshops on weekends and in the summer. At the end of that time, they are certified by the American Montessori Society, one of the two main U.S. Montessori certification bodies.

Just this winter, Principal Wilson of Anderson Academy and Reece Principal Stephanie Y. Rhodes persuaded the school board to pay each Montessori teacher an extra $1,500 a year, which they hope will help in attracting and keeping more Montessori instructors. Two classrooms—part of an eight-room addition to Reece last year—stand unused in part for lack of teachers.

While there may be openings for teachers, there is no lack of students. Last month, some 1,050 families were waiting for places at the district’s 13 magnet schools— which offer special programs to draw racially and ethnically diverse students. Of those, 255 were waiting for Reece, which sends most of its students on to Anderson. Anderson had a waiting list of 129 students.

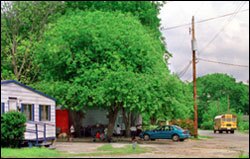

Acres Homes got its name from the tradition of selling land by the acre rather than by the lot in the original development of the area for black families around World War I. The neighborhood remains overwhelmingly African-American and hugely spacious, with a mix of neat and dilapidated houses set among oak trees near the roar of Interstate 45. Acres Homes’ children go to school in three districts, including the Houston Independent School District and Aldine, which stretches beyond the city limits to encompass miles of largely working-class suburbs.

The seed for the hybrid schools was a desegregation suit in the 1960s that led to widespread busing of black students out of the schools in the Aldine district’s part of Acres Homes. In the early 1990s, some Acres Homes leaders sought to reverse the busing policy, at least for their neighborhood. As Aldine officials devised a plan to mix the area’s black, Hispanic, and white students through magnet schools, Acres Homes leaders pressed for better schools closer to home.

By that time, the Montessori movement had spread to more than 60 public school districts nationwide, in many cases as a tool to attract the white, middle-class families who knew the approach from private preschools. When groups of district residents were asked to focus on the kind of school that would appeal to them—enough to send their small children on 50- minute bus rides across the district—many put a Montessori program high on their lists.

Meanwhile, the leaders in Acres Homes were pressing for a different program—one that the community’s Wesley Elementary School, in the adjacent Houston school district, had used with such success. Direct Instruction was the choice of Principal Thaddeus S. Lott, whom educational traditionalists have held up as the type of no-nonsense, high-expectations leader that failing schools need.

|

Jordan Lane, 7, sounds out “th” with the rest of her class during Direct Instruction lessons in Carrie Miller’s 1st grade class at Anderson Academy, which opened in 1995. |

“We went in there and looked at what he was doing to raise up children who were supposed to fail before they were born,” says Roy Douglas Malonson, a local businessman and activist who heads the Acres Homes Citizens Chamber of Commerce. So Malonson thought: Why not have both programs?

“People from outside the district and from within told us we were crazy, to put it bluntly,” recalls Kay Massey, the district’s superintendent for magnet schools. “How could you have a principal who was the instructional leader of programs which were the exact opposite of each other?”

They did it anyway—but carefully. The Reece and Anderson programs opened in 1995: Anderson in a made-over building and Reece in temporary quarters. They were designed as part of a magnet feeder pattern, with all five schools located in Acres Homes.

In addition to Reece and Anderson, Acres Homes now has magnet intermediate, middle, and high schools. All are obligated by an amended desegregation order to reserve enough places in the schools so that African-American children constitute no less than 15 percent above or below their proportion in the district as a whole—34 percent.

Accepting all the neighborhood children who apply, the schools in the feeder pattern enroll 46 percent black students, 53 percent Hispanic, and 8 percent white. District officials hope to keep up with at least most of the growth in demand by opening a new school in the strand in 2003-04.

But only the two schools for the youngest children combine two different teaching approaches. The other schools offer the same beefed-up fine arts as Reece and Anderson. But neither the Montessori nor the Direct Instruction approach is continued.

One of the keys to the success of Reece and Anderson, says Massey, was the decision to give each school two assistant principals, one for the Direct Instruction classrooms and one for the Montessori classrooms.

School leaders say they tried to be attentive to other kinds of balance as well. For instance, Montessori classrooms represent an initial investment of some $30,000, and the program requires that teachers have an aide. So the officials made sure that Direct Instruction teachers also have aides, as well as a rich supply of materials.

“At the beginning stage, the job is harder,” admits Rhodes, the Reece principal, about making sure all the teachers are pulling together. Common times for planning lessons helped, she says, as did committees that pulled in teachers from the two “worlds.”

The principals offer evenhanded support for both approaches, to a fault, serving as advocates for Montessori and Direct Instruction within their school communities and as cheerleaders for the schools generally.

|

Local children play in the shade near Anderson Academy as one of the more than 60 buses that serve the school passes by. The buses cover more than 100 square miles. |

At Anderson, the passing rates on the 2001 state tests for 3rd grade reading and math put the school among the state’s top 10 schools with comparable or more needy populations, according to the research group Just for the Kids in Austin. (Another school in the district— with 90 percent of its pupils from low-income families, compared with Anderson’s 70 percent—did even better.)

Equally important, the trend lines for Anderson Academy pupils’ attainment of the “proficiency” level have been upward in both reading and math. Almost 80 percent of the 3rd graders were “proficient” last year in reading; about 60 percent in math.

The principals say that when they have looked at the test results by program, there is little difference, with Montessori students sometimes showing a small advantage in math and Direct Instruction students in reading.

That conclusion is seconded by a spokeswoman for Houston’s Annenberg Challenge, a philanthropy that has given millions of dollars to schools in six area districts. “We’ve looked at academic achievement of both types of instruction, and the kids show pretty much equal gains,” says Nan Varoga, the group’s spokeswoman, adding, “They’ve been focusing resources on professional development for both.”

So the question for the schools becomes just this: Which approach fits an individual student best?

“That’s the beauty of the school,” says Wilson, the Anderson principal. “We have two very diverse programs that are meeting the different learning styles of children.”

As well as the preferences of parents.

When parents apply for their child’s admission to the school, they must specify their choice of either the Direct Instruction or the Montessori program. The school tries to prepare them for that choice by hosting sessions that demonstrate the differences between the programs.

And parents seem to relish having the choice, whether or not they think deeply about it.

Leaning out of her school bus window last month, a Hispanic mother who is employed by the district as a driver says she wanted Anderson Academy for her youngest child because of the individual attention.

Why Montessori? “I heard great things about that from parents I knew,” she says.

Another mother, who is white and substitute teaches at Anderson, struggled with the choice in the case of both her children. The older one, a boy, is “very artistic, but we weren’t sure he had the focus to drive himself in a Montessori program,” she says. He went through Reece and Anderson as a Direct Instruction student.

Her daughter, on the other hand, was enrolled as a Montessori student. That had been the parents’ second choice, but still one they were comfortable with. On a tour, the mother recalls, “We walked into the Montessori rooms, and I was overwhelmed by all the stuff. But she was like a duck in a pond.”

The experience has been a good one, but with their daughter approaching 3rd grade and continuing to have trouble spelling, the parents requested a switch this year to a “DI classroom.” That, too, is working out well, according to the mother.

|

Kaulen Applin, 7, practices a collection of songs he has memorized. His school, Anderson Academy, lends students musical instruments, such as this violin, so that they can practice at home. The school’s string ensemble requires auditions. |

Such switches are not commonmaybe a dozen children out of 600 a year, Wilson estimates. The schools try to admit and keep equal numbers of children in the two programs.

What’s striking in talking to parents is the variety of different ways that the schools appeal to them. Even without the choice between Montessori and Direct Instruction, the offerings are considerable.

“Where else can you give your child piano lessons during the school day?” sums up Aldine Superintendent Nadine Kujawa.

About 100 children in each school, to give another example, receive instruction for a substantial part of the day in Spanish, mostly in Montessori classrooms. More than 300 at Anderson are enrolled in extensive before- and after-school programs, including tutoring, which stretch the school day from 7:30 a.m. to 6 p.m., if a parent wishes.

Some parents are probably also aware that Anderson has been named an “exemplary” school under the Texas rating system for three years in a row.

“There are so many things offered,” says an African-American mother whose son is on the school’s waiting list. “I wanted more for [my son]” than his current school.

In a way, the two schools show what can happen when resources are applied to the right list of priorities: sound curriculum, teacher training, and good leadership. But it’s hard not to recognize the extra boost that comes from the choices built into Reece and Anderson—choices that help make parents and teachers alike more knowledgeable and committed.

“I get more involved parents, I certainly do,” muses Wilson, who has worked as a teacher and an administrator in Aldine for 25 years.

Still, if Wilson had to pick out one thing that makes a difference for the quality of the schools, it would be the staff.

“I really don’t think the magic is in the programs,” though it’s important they be sound, the principal continues. “The magic is in the people teaching the programs. They believe in the programs, and they are extremely well-trained.”

Around the corner in her classroom, 1st grade teacher Misty D. Lo is still thanking her lucky stars for Anderson Academy. Before coming to the school two years ago, she piloted Direct Instruction at another Aldine school, where seven different reading programs were being tried. The 29-year-old Iowa native saw the potential of Direct Instruction, but knew neither she nor her children were reaching it.

Transferring to Anderson, she got more intensive training, joined colleagues committed to the method, and was assigned children who had been under the same regime at Reece.

Though the programs are costly, teachers and parents say the extra effort are worth it in order to have the added choices.

“I came here because of the program,” says the pony-tailed young woman, who is wearing an Anderson T-shirt and a denim shirt embroidered with the school’s name. “Without it, I don’t know how effective a teacher I would be. None of our students are falling through the cracks.”

To the contrary, 7-year-old Zayna seems ready to soar when it comes to the written word. Just a few minutes earlier, the bespectacled little girl earned praise from her teacher for recognizing that a sentence she was reading to her classmates was about a “kite,” not a “kit.”

“Zayna, wonderful!” Lo exclaims, explaining to the group: “She went back and corrected herself. That’s what a good reader does.”

And here’s what a good reader like Zayna likes: “Taking books home, reading with my mom and dad, reading with my friends, and,” she adds, “with my teacher.”