In a presentation to educators on July 20, the head of the Advanced Placement program for the College Board, Trevor Packer, spoke of major decisions the College Board made since the start of the pandemic that generated controversy, including edits to its African American studies course, and provided some insight into where programs were headed.

Thousands of teachers and school and district leaders gathered last week for the College Board’s Advanced Placement annual conference, its first since 2019.

Workshops and sessions covered developments in AP from transitions to digital testing, to two high profile new courses in precalculus and African American studies. Equity and access to AP courses—which offer students the possibility of earning cost-saving college credits in high school—were a major theme throughout.

The AP African American Studies pilot, AP Psychology, and Florida

The College Board made national news this year when edits were made to the AP African American Studies pilot course framework.

Specifically, Packer detailed the tumultuous rollout of the framework.

His timeline of events began with a January letter from the Florida Department of Education in which state officials claimed the course “lacks educational value.” The letter was later followed by a tweet from the state’s commissioner of education, Manny Diaz Jr., citing topics of concern including “Intersectionality and Activism” and “Black Queer Studies.” (State law in Florida, as in a number of Republican-led states, restricts instruction on topics of race, gender, and sexual orientation.)

By the time the College Board published the AP African American Studies course framework on Feb. 1, it did not address those topics.

“So what did that look like to the public? Exactly what it looked like to the public, that the College Board had made changes to appease one governor’s agenda, and one state’s agenda at the expense of 49 other states’ priorities,” Packer said.

“We were caught off guard, we attempted to protest, to explain what we were doing. We were not especially effective at doing that. And we ultimately decided to empower the committee, professors that are content experts that work on AP African American studies, to make further revisions to the framework to restore any of the topics that they would want to restore that we were criticized for cutting.”

He added that the organization never “colluded” or “collaborated” with Florida but rather that College Board officials were thinking of the larger political climate of the country in their decisions over what to include in the course. Course framework edits are currently underway ahead of a second pilot year for the course in which more than 700 schools are expected to participate, up from the 60 that participated in the first pilot year.

Packer said that in the creation of the course, there was an initial intent to require daily readings that aligned with texts studied in college level African American Studies courses, such as “The Souls of Black Folk” by W.E.B. Du Bois.

But at least 18 states have imposed bans and restrictions on instruction of race in K-12 schools.

“In preparing for the second year of the pilot, we removed some of the readings that would make the course illegal in particular states. We removed particular topics that would have made it illegal for a teacher to teach this class,” Packer said.

“We’re trying to decide how can we make this course a course that will not put teachers’ livelihood at risk, and that will be available to students regardless of where they live. At the same time, we’re trying to make it a college level course that colleges will be proud of and will be willing to give college credit. That was our attempt, and we were not successful in that attempt.”

Earlier this year, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who is also a Republican presidential candidate, banned the course in the state for allegedly defying state law.

“A ban on a college level course is unprecedented,” Packer said. “We believe in parental choice. It has been a hallmark of the AP program for 68 years. And we call upon all 50 states to revert to principles in which parents have the right to choose whether their students take an AP course rather than taking that option away from them.”

Packer also referred to Florida officials’ May request for potential edits to the organization’s AP psychology course, which includes a required topic of instruction on gender and sexual orientation. State law bans instruction on gender identity and sexual orientation in grades K through 12.

In a letter sent to AP educators in June, however, the College Board affirmed it would not make any edits to pre-existing AP courses per state requests, which Packer affirmed at the AP conference.

The future of AP

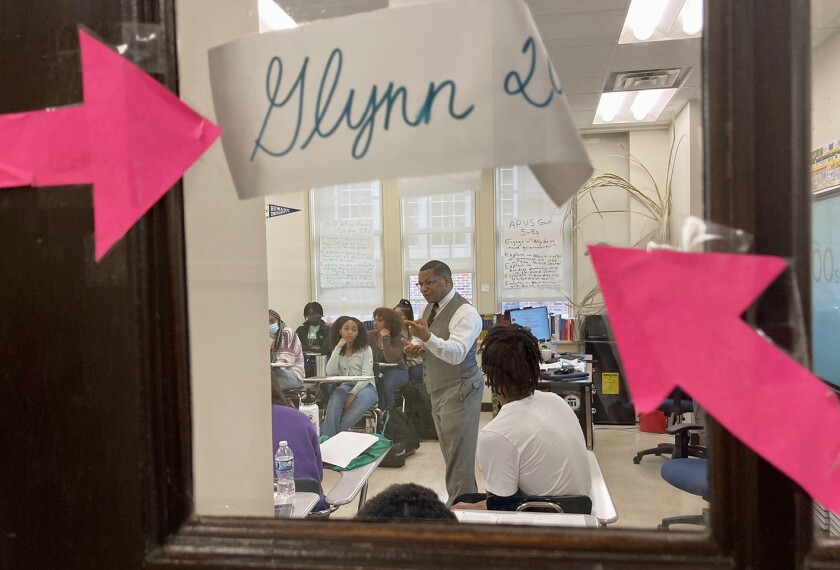

Looking ahead, Packer spoke of the importance of expanding access to AP courses to underrepresented student groups.

Citing College Board data, he said, about 7 percent of students take six or more AP courses before graduation, about 28 percent take one to five, and about 65 percent take none.

Outcomes in college don’t necessarily improve all that much for those taking multiple AP courses. But improvements can be more substantial for students least likely to take a bulk of AP offerings.

“Our research shows that taking and performing well on more than four to six AP exams does not markedly alter first year college grades and four year degree completion,” Packer said.

69´«Ă˝ who enter AP below the 50th percentile of their class have the most to gain from AP courses with a 14 percent boost in the likelihood of on-time college graduation compared to an 11 percent boost to those in the 50-95th percent and a 5 percent boost to those about the 95th percentile, Packer added.

He urged educators to re-evaluate how many seats they offer in AP courses and who takes up the bulk of them to ensure fair access. One example would be to consider the new AP precalculus course launching this fall as a course specifically for students who otherwise may not be on track to earn AP math credits.

In a later session, Packer also previewed some potential developments ahead for the College Board, including more digital testing for AP courses, and an entry into career and technical education for the organization in the form of a pilot program called Career Kickstart, which would offer schools career-oriented high school courses in fields such as cybersecurity.

Packer also shared the results from a number of changes the College Board has made to AP in the past three years.

Requiring students to register for AP exams in the fall

For decades the College Board allowed students the flexibility to decide when to register to take AP exams, including up to the night before the exam. That changed in the last few years when the organization moved to require registration in the fall as part of a $90 million effort to get more students of color and female students to sign up for AP exams, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and math courses, Packer said.

Since the move to require fall registration, the organization saw both an increase in underrepresented students taking exams and a boost in exam performance, he added.

Online testing in spring 2020

When the pandemic upended the 2019-20 school year, the College Board moved to shorter online testing as an immediate response.

“There was not 100 percent agreement among teachers or students that we should offer AP tests during the pandemic,” Packer said.

Educators argued that it would stress out students and result in uncontrolled testing environments. Surveyed students, meanwhile, said they wanted the chance to still earn college credit while in remote learning, Packer said.

Nationally, students ended up qualifying for $3 billion in college credits through May 2020 testing, he added.

Since then, some AP courses have continued to offer digital testing options with the organization exploring whether and how to expand them.

Offering content videos as instructional resources

Though the College Board sets course requirements that must be taught, the organization generally doesn’t prescribe how teachers should go about covering them.

Yet at the start of the pandemic, the College Board wanted to assist educators in navigating remote learning by creating AP Daily videos for every topic in every AP course. The free videos allowed students to follow along if they missed class, or offered additional support if they were struggling with a concept, Packer said.

The organization now seeks input from educators as to whether these resources are still helpful as most schools have re-adjusted from remote learning.