Recent moves by state leaders have reenergized a debate: Is teaching about the Bible in public schools necessary to develop well-rounded, culturally literate students? Is it possible to do so without violating the Constitution or unfairly singling out students of various faiths—or those with no faith at all?

Oklahoma Superintendent Ryan Walters, who has called the separation of church and state a myth, issued a June 26 memo to school districts, directing them to incorporate the Bible into classes for 5th through 12th grades. “Immediate and strict compliance is expected,” he wrote.

Walters later announced a committee to review the state’s social studies standards and incorporate the Bible “as an instructional resource.”

His directive came a month after the Texas Education Agency proposed optional new elementary school English/language-arts materials that include references to the Bible alongside information about science and stories from history.

A 2nd grade unit on “fighting for a cause” includes the story of Queen Esther. A 3rd grade unit on the Roman empire calls for students to read passages about the birth, crucifixion, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Texas officials said the scripture references provide important background knowledge to help students build reading comprehension.

Oklahoma will bring the Bible “back to our schools” because it is a a “momentous historical source” frequently cited in the 1600 and 1700s, Walters in a July 1 interview.

“The Left can be offended, they can be mad, they can be upset, but what they can’t do is they can’t rewrite history,” he said, predicting success with former President Donald Trump’s nominees to the U.S. Supreme Court if the state faces a legal challenge over the directive.

But some skeptics—including scholars who study the role of religion in public schools and efforts to teach the Bible in academic settings—panned Walter’s directive as another effort to insert Christianity into public life as the country becomes more religiously diverse.

“I think there’s a strong case to be made that biblical literacy is an important component of a broader religious literacy that is itself an essential component of cultural literacy, and that a broad religious literacy is essential in a religiously diverse democracy,” said Mark A. Chancey, a professor of religious studies at Southern Methodist University who studies Bible courses in public schools. “But it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that [Walters] is trying to promote his own particular religious views over those of everyone else.”

The that while academic lessons on the Bible are permissible, devotional readings in public schools violate the establishment clause in the First Amendment, which protects Americans’ free exercise of religious beliefs.

Among Chancey’s concerns: Walters’ directive focused specifically on the Bible and no other religious texts, and the committee he assembled to review Oklahoma’s social studies standards includes , who rejects the notion that the U.S. Constitution protects religious pluralism.

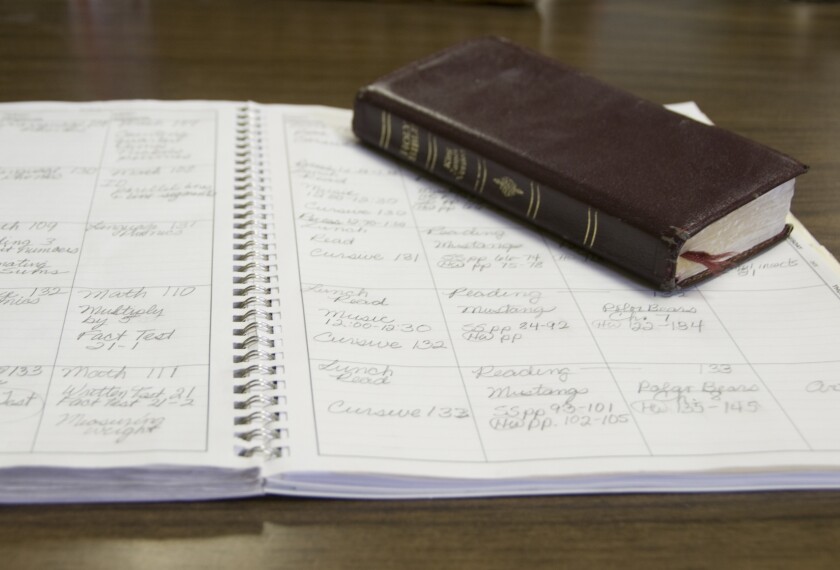

The American Academy of Religion and the American Historical Association both condemned Walters’ directive, saying in statements that it “shrinks rather than expands religious literacy” by presenting a narrow view of the role of Christianity in the nation’s founding. And at least one leader, Norman schools Superintendent Nick Migliorino, said his district will not comply with Walters’ order or with his insistence in a June 27 state board meeting that “every teacher in the state will have a Bible in the classroom.”

“We’re gonna follow the law, we’re going to provide a great opportunity for our students, we’re going to do right by our students and right by our teachers, and we’re not going to have Bibles in our classroom,” Migliorino

A spokesperson for the Oklahoma department of education responded to emailed questions about Walters’ order by sending a press release about the social studies review. He did not respond specifically to questions about when state officials would provide schools additional resources on fulfilling the mandate or whether the agency would provide guidance on selecting a translation and respecting the rights of students from various religious backgrounds.

Connecting the Bible to background knowledge for reading

Among the newer arguments being used to bolster teaching the Bible is one that connects to the national conversation about reading. Supporters of calls to incorporate scripture into classwork argue students need a basic level of biblical literacy to understand common references in literature, stories depicted in significant art pieces, and the perspectives and beliefs of historical figures.

Research has long shown that background knowledge is linked to students’ ability to understand what they read. And more districts are exploring “knowledge-building curriculum,” an approach to English/language arts instruction that aims to systematically grow students’ knowledge about the world by using texts that incorporate literature, the arts, and science and social studies’ concepts to build vocabulary and fuel reading comprehension.

Now, some argue that familiarity with historically significant books like the Bible is an equity issue. Ensuring students have a basic knowledge of the text ensures there aren’t “language have-nots” who will always be at a verbal disadvantage, Robert Pondiscio, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, (Walters has since named Pondiscio alongside big conservative names like Barton, radio host Dennis Prager, and Heritage Foundation President Kevin Roberts.)

“Speakers and writers make assumptions about what listeners and readers know,” Pondiscio wrote. “Not just vocabulary, but a vast array of literary and historical allusions and idioms, including biblical references—Pandora’s box, a pound of flesh, prodigal son, good Samaritan, David and Goliath, forbidden fruit, white whale, to name but a few. These and countless other examples act as a kind of shorthand for complex ideas and concepts.”

Pondiscio cited E.D. Hirsch, a University of Virginia professor whose 1987 book Cultural Literacy included a list of 5,000 references, dates, and other bits of knowledge he claimed to represent the ideas shared by literate Americans. (That appendix lists Christianity as a topic as well as several references from biblical literature, but does not specifically name the Bible.)

Teachers face common pitfalls in teaching about the Bible

But even well-intentioned efforts to teach about the Bible can be fraught with challenges, said Chancey, the Southern Methodist University professor. And broad, unclear directives about Bible-teaching often overlook those difficulties.

For one thing, teachers must navigate differing views, even among Christian students, about how the text should be interpreted an applied, Chancey said. Even selecting a Bible translation can be tricky because various Christian sects differ on perspectives about accuracy and even which books to include. And teachers may not recognize the personal biases they carry about reading scripture.

“One of the biggest stumbling blocks is presentation of the Bible as straightforward and unproblematic history, which is in effect making a religious claim,” Chancey said.

People, including teachers, often read the Bible through “the interpretive lens with which they are most familiar,” sometimes without recognizing that other interpretations exist, he said. For example, a teacher may present the prophetic books of the Hebrew Torah or Old Testament as a foretelling of the birth and death of Jesus Christ without acknowledging that that viewpoint is not shared by Jews.

“Intentionally or not, Bible courses are often taught from religious perspectives, with the result that some students find their own beliefs endorsed in the classroom while others find theirs disparaged or ignored,” Chancey wrote in commissioned by the Texas Freedom Network, an organization that promotes the separation of church and state.

Using public records requests, Chancey obtained syllabi, quizzes, handouts, and other classroom materials from districts around the state to examine how educators taught elective Bible courses offered under a 2007 state law. That law also requires K-12 districts to incorporate “religious literature, including the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) and New Testament, and its impact on history and literature” into their required curricula.

Common concerns Chancey observed:

- Teachers—many who had never had a college-level course in biblical or religious studies—often lacked training to teach the Bible in an academic way. In some cases, districts hired local Christian pastors to teach the courses.

- Courses varied greatly in rigor and approach. Lessons included weekly requirements to memorize verses, a common practice in church Sunday schools; inaccurate or conflicting facts about the history of the Bible; and showing movies like Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” in class.

- Teachers discussed Judaism in the Bible “through Christian eyes,” suggesting that Christ’s teachings in the New Testament supersede the covenant God made with the Jewish people in the Old Testament.

- Materials included inaccurate quotes about the role of the Bible in the nation’s history.

Why switching between devotional and academic points of view be difficult

Teaching about the Bible can also create challenges for nonreligious students or those from minority faiths in classrooms where a majority of their classmates interpret the text through a similar Protestant lens, said James W. Fraser, professor of history and education at New York University and pastor emeritus of Grace Church in East Boston, Mass.

69��ý may have difficulty shifting between the devotional use of the Bible outside of the classroom to a purely academic approach at school, he said, and that can create a sense of isolation for those who don’t view the text in a similar way.

“I worry that in this day and age, mandating [teaching the Bible] is going to put it in the hands either of teachers who are hostile to it or teachers who want to turn it into the truth and teach it that way,” Fraser said. “Both of those perspectives can be very harmful to large numbers of students.”

Debates over teaching the Bible are woven throughout the nation’s history, said Benjamin Justice, a professor of educational theory, policy, and administration at the Rutgers University Graduate School of Education who has written several books on religion and public schools.

In the 19th century, the nation’s Protestant majority emphasized “the greatest common denominator” in schools, adopting practices that ran counter to the Catholic minority’s traditions. 69��ý adopted the King James Bible, a translation favored across many Protestant denominations that excludes included in the canon used by Roman Catholics.

Leaders believed they found an answer to Catholics’ concerns about differing interpretations of scripture by directing schools to read the Bible without “note or comment.” But that solution created problems of its own, Justice said, because, while Protestants value individual interpretation of scripture, Catholics rely on Church authorities to help understand and apply the text. Open-ended reading of the text violated Catholic students’ religious values, creating conflict.

Those challenges could persist today if schools favor a Protestant interpretation of the text, Justice said.

“It’s actually violating a child’s First Amendment right to tell them that their interpretation of the Bible is wrong,” he said.

The challenges of presenting the text without favoring or excluding any particular religious group have only grown more complex as the nation has grown more religiously diverse, Justice said. He called Walters’ order a “baldly political ploy.”

“I don’t believe that this is a good faith effort to give kids a better education,” Justice said.