The day we can accurately measure a teacher’s performance has finally arrived. Or so the likes of District of Columbia 69��ý Chancellor Michelle A. Rhee and New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg would have us believe.

In a speech this past fall in Washington, but directed at the New York state legislature, “data-driven systems,” while arguing that student test scores should be linked to teacher-tenure decisions. His preferred analogy was to medicine: To prohibit the use of student test-score data in such decisions, Bloomberg explained, would be as insane and inane as “saying to hospitals, ‘You can evaluate heart surgeons on any criteria you want—just not patient-survival rates.’ ”

John Merrow, the education correspondent for “PBS NewsHour,” favors instead the : If half the class nearly drowns when trying to demonstrate what they’ve learned, we’d be downright daft not to find fault with the teacher.

The logic behind both analogies is seductive. If someone’s job is to teach you something and yet you don’t learn it, or you aren’t able to demonstrate you’ve learned it, then isn’t the only reasonable conclusion that the teacher has failed you?

People like Rhee, Bloomberg, and Merrow are so certain of their positions—and so wildly confident in the data—that another perspective seems all but impossible. The clear implication is that to disagree with them, you’d have to be mentally ill, hopelessly naive, or wholly heartless.

But as seductive and seemingly straightforward as their logic appears, it also turns out to be deeply flawed.

Merrow’s analogy, for instance, ignores a very important reality: A 10-year-old who’s ostensibly been taught to swim has much greater motivation to successfully display his newfound knowledge in the pool than do students who’ve been taught fractions in math class. No math student has ever drowned because he couldn’t multiply one-half by one-third.

Rhee, Bloomberg, Merrow, and the many others now beating the fashionable drum of “data driven” accountability in education—right on up to U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and President Barack Obama—seem determined to ignore some basic truths about both education and statistical analysis.

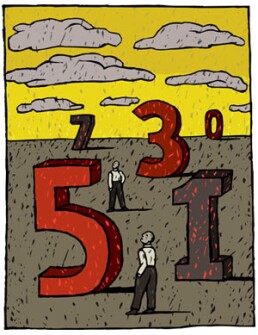

Numbers impress. But they also tend to conceal more than they reveal."

First, when a student fails to flourish, it is rarely the result of one party. Rather, it tends to be a confluence of confounding factors, often involving parents, teachers, administrators, politicians, neighborhoods, and even the student himself. If we could collect data that allowed us to parse out these influences accurately, then we might be able to hold not just teachers but all parties responsible. At present, however, we are light-years away from even understanding how to collect such data.

Second, learning is not always, or easily, captured by high-stakes tests. A student’s performance on a given day reflects a whole lot more than what his teacher has or hasn’t taught him.

When it comes to school accountability, today’s favorite catchphrase is “value added” assessment. The idea is that by measuring what students know at both the beginning and the end of the school year, and by simply subtracting the former from the latter, we’re able to determine precisely how much “value” a given teacher has “added” to his or her students’ education. Then we can make informed decisions about tenure and teacher compensation. After all, why shouldn’t teachers whose students learn more than most be better compensated than their colleagues? Why shouldn’t teachers whose students learn little be fired?

The short answer to both questions is because our current data systems are a complete mess. We tend to collect the wrong kinds of data, partly to save money and partly because we’re not all that good at statistical analysis.

The accountability measures of the federal No Child Left Behind Act, for instance, are based on cross-sectional rather than longitudinal data. In layman’s terms, this means that we end up comparing how one set of 7th graders performs in a given year with how a different set of 7th graders performs the following year. Experts in data analysis agree that this is more than a little problematic. A better system—one based on longitudinal data—would instead compare how the same set of students performs year after year, thereby tracking change over time. But these are not the data we currently collect, in large part because doing so is difficult and expensive.

There’s no denying that we love data. Indeed, we are enthralled by statistical analyses, even—or especially—when we don’t understand them. Numbers impress. But they also tend to conceal more than they reveal.

Every educator knows that teaching is less like open-heart surgery than like conducting an orchestra, as the Stanford University professor Linda Darling-Hammond has suggested. “In the same way that conducting looks like hand-waving to the uninitiated,” she says, “teaching looks simple from the perspective of students who see a person talking and listening, handing out papers, and giving assignments. Invisible in both of these performances are the many kinds of knowledge, unseen plans, and backstage moves—the skunkworks, if you will—that allow a teacher to purposefully move a group of students from one set of understandings and skills to quite another over the space of many months.”

Until we get much better at capturing the nuances of such a performance, we should be wary of attempts to tie teacher tenure and compensation to student test scores.