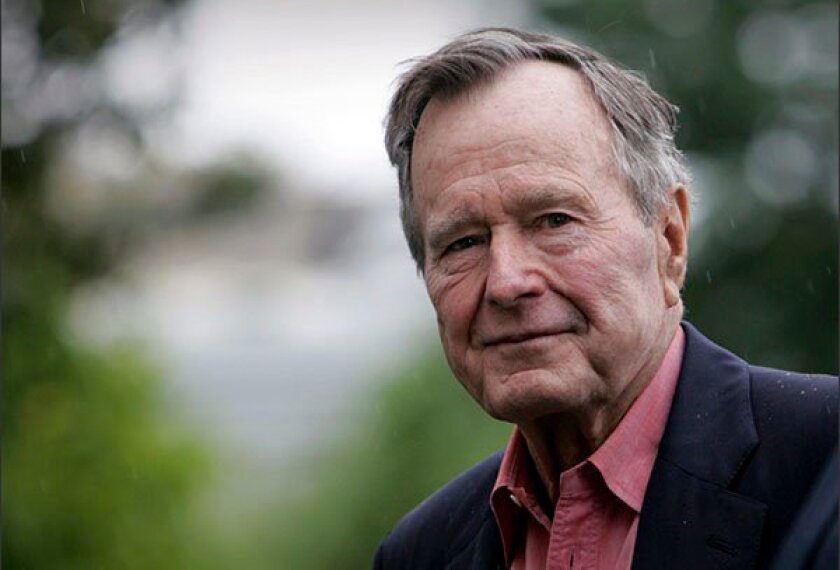

George H.W. Bush, who styled himself as the “education president” and spearheaded a historic 1989 summit meeting with governors that helped propel the standards-based education improvement movement, has died at age 94.

Bush died in Houston on Friday night. Bush’s wife of 73 years, Barbara Pierce Bush, died April 17 at age 92.

“George H.W. Bush was a man of the highest character and the best dad a son or daughter could ask for,” his eldest son, former President George W. Bush, said on Instagram. “The entire Bush family is deeply grateful for the 41’s life and love, for the compassion of those who have cared and prayed for Dad, and for the condolences of our friends and fellow citizens.”

Bush served a single term as the 41st U.S. president, from 1989 to 1993, after years of government service that included member of Congress, ambassador, director of the Central Intelligence Agency, and vice president for eight years under President Ronald Reagan.

He was seeking to seize an issue for his 1988 campaign for the Republican presidential nomination when he stood before an audience of high school students in New Hampshire and declared, “I want to be the education president.”

“I want to lead a renaissance of quality in our schools,” Bush said at Manchester High School in January of that year.

The candidate would return to the theme and to the “education president” tagline throughout the primary season and the general election campaign, in which Bush defeated Democrat Michael S. Dukakis.

Centerpiece Goals

Upon taking office, Bush would soon begin planning a major policy summit on education goals, held in September 1989 on the campus of the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville.

The two-day summit included the participation of 49 of the nation’s governors (Rudy Perpich, Democrat of Minnesota, was the lone absence), as well as business leaders and policymakers. It concluded with an agreement to develop national education goals and take other steps to improve the nation’s schools.

“The American people are ready for radical reforms,” the president said after the two-day summit. “We must not disappoint them.”

A key participant in the summit and the ensuing efforts to hammer out the details of the goals was Bill Clinton, then the 43-year-old Democratic governor of Arkansas who would go on to defeat Bush in the 1992 presidential election.

After months of post-summit meetings that generally included Clinton, at that time a leader of the education task force of the National Governors Association, and Roger B. Porter, Bush’s domestic-policy adviser, the goals became a centerpiece of Bush’s State of the Union address in January 1990.

By 2000, Bush told the country, every child in the United States would start school ready to learn, and the high school graduation rate would rise to at least 90 percent. Every American adult would be a literate and skilled worker. The nation would lead the world in math and science achievement. 69��ý would be safe and drug-free.

And, most critically: Every student would leave grades 4, 8, and 12 having demonstrated competency in English, mathematics, science, history, and geography.

“Ambitious aims? Of course. Easy to do? Far from it,” Bush said in the address before Congress. “But the future’s at stake. The nation will not accept anything less than excellence in education.”

‘Cocky’ and ‘High Hat’

George Herbert Walker Bush was born June 12, 1924, in Milton, Mass., the second of five children of Prescott Bush and Dorothy Walker Bush. The elder Bush was a businessman who was elected to the U.S. Senate from Connecticut in 1952 to fill a vacancy created by the death of an incumbent. He was re-elected to a full term in 1956 and left office in January 1963.

Among the wealthy family’s homes was a compound in Kennebunkport, Maine, that George H.W. Bush would visit frequently during his White House years.

Bush was 5 years old when he entered Greenwich Country Day School in Connecticut in 1929, starting 1st grade a year early so he could be with his older brother, Prescott Bush Jr., according to Jon Meacham’s biography of the president, Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush.

The boys were chauffeured to school by the family driver to the elite private school, where they learned Latin. In 1937, Bush entered Phillips Academy, an Andover, Mass., boarding school founded in 1778 that extolled its motto of accepting “youth from every quarter.”

Bush struggled there at first, according to Meacham’s biography, with a counselor’s report that the young student was “not well measured in all respects” and was “cocky and ‘high hat’.” By his second year, he had improved considerably. But Bush missed much of his junior year due to illness, which pushed his graduation back to 1942.

His yearbook entry reflects an abundance of extracurricular activities: president of the senior class, captain of the baseball and soccer teams, member of the basketball team, chairman of student deacons, and treasurer of the student council.

Bush visited Andover, as the school is sometimes called, as president in November 1989 to help the school mark the bicentennial of a visit by George Washington.

“The Andover Mission states that education has always been the great equalizer and uplifter,” the president said. “And that, public or private, large or small, the schools of America are precious centers of intellectual challenge and creativity.”

“And yet, they’re more than that,” he continued. “For it is in school, as it was for me here at Phillips Academy, that we come to understand real values. The need to help the less fortunate, make ours a more decent, civil world.”

Bush was in his senior year at Phillips Academy when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor occurred on Dec. 7, 1941. He quickly decided he wanted to serve his country, and that he would join the U.S. Navy to become a pilot. In a 1944 attack on the Japanese in the Bonin Islands, the plane Bush was piloting took anti-aircraft fire and his engine caught fire. Bush opened a gash on his head as he parachuted out of the plane, and he was rescued from a life raft by a U.S. submarine. Bush’s two fellow crew members were never found, a loss that had a profound effect on him.

Bush’s military service put off his college education, but not his marriage to Barbara Pierce of Rye, N.Y. They had met at a Christmas dance in 1941 in Rye while Pierce, then 16, was home from Ashley Hall School in Charleston, S.C., and Bush was at Andover.

Bush and Pierce married in 1945. Bush enrolled in Yale University, where he studied economics, was captain of the baseball team, and graduated on an accelerated schedule after two-and-a-half years.

The family moved to West Texas, where Bush pursued a career in the oil business, which he continued with a move to Houston in 1959. In 1964, Bush ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate, then won election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1966. In 1970, President Richard M. Nixon convinced Bush to again run for Senate against Democrat Ralph Yarborough, who had defeated Bush in 1964. But Yarborough lost his Democratic primary to Lloyd Bentsen, who went on to defeat Bush.

In the ensuing years of the Nixon and President Gerald R. Ford administrations, Bush served as ambassador to the United Nations, chairman of the Republican National Committee, envoy to China, and director of central intelligence.

Bush retreated to private life during the administration of President Jimmy Carter, but he decided to run for the Republican presidential nomination in 1980. He defeated Ronald Reagan in the Iowa caucuses and declared that his campaign had gained the momentum, or “Big Mo.”

But Reagan won the nomination, and he selected Bush as his running mate on the eve of the Republican convention. Bush had not shown a great interest in education policy as a presidential candidate or throughout eight years as Reagan’s vice president.

‘He Seems to Feel It and Mean It’

In September 1988, Bush accepted the Republican nomination for president at the party’s convention in New Orleans. In a forum during the convention, Terrel H. Bell, Reagan’s first secretary of education, declared that he believed Bush was sincere in his often-stated commitment to improve education based on evidence from his years as vice president.

“Every time education matters came up at Cabinet meetings,” Bell said, “Bush was on the edge of his seat, telling Cabinet members and the president that human resources is the whole ballgame. I believe he means it when he says ‘I want to be the education president.’”

Bell, who was at the helm of the Education Department when the groundbreaking report “A Nation at Risk” was released in 1983, joined his successor as secretary, William J. Bennett, in a coalition of educators in support of Bush’s presidential campaign.

Lamar Alexander, then a former governor of Tennessee with wide education-policy experience and now the chairman of the U.S. Senate education committee, was a member of Bush’s education-advisory panel during the 1988 campaign.

“When he says he wants to be the ‘education president,’ it is not a canned statement contrived by a consultant,” Alexander told Education Week at the time. “That’s one of the things that impresses me—he seems to feel it and mean it.”

The most discussed education issue during the 1988 campaign involved not standards or goals, but the Pledge of Allegiance.

Dukakis, the Democratic presidential nominee, had in 1977 vetoed a bill as governor of Massachusetts requiring public-school teachers to lead their students in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance every morning. He was acting on the advice of the state’s highest court, which had pointed to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1943 decision in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, which struck down that state’s law requiring students to salute the flag and recite the pledge. (Massachusetts lawmakers overrode Dukakis’s veto, though the law was never enforced.)

Bush hammered Dukakis on the issue and announced that he would have signed the Massachusetts law, in keeping with the Republican platform promise to protect the pledge in schools. The debate dominated the campaign for weeks, to the consternation of many educators and policymakers.

“There are so many other things that they should be discussing,” a Minnesota private school headmaster told Education Week.

A Summit and Goals

Meanwhile, the headline-generating Bennett had left the Cabinet late in the Reagan administration and been replaced by the low-key Lauro F. Cavazos, who was the president of Texas Tech University, a friend of Bush’s, and the first Hispanic to serve in a presidential cabinet.

When Bush won election, he announced that he would keep Cavazos as his education secretary. But by the time of the of the Charlottesville summit, Cavazos was reduced to introducing the president and standing by his side at news conferences. He was not viewed as an especially influential player.

Bush felt most comfortable working with his White House domestic-policy aides, such as Roger B. Porter, and governors active in education policy such as Clinton, a Democrat, and Republicans such as Terry Branstad of Iowa and Carroll Campbell of South Carolina.

At the end of the summit, Bush singled out a few of the governors, including Clinton, “who looks a little tired, but took on an extra responsibility in hammering out a statement upon which there is strong agreement.”

“This is the first time in the history of this country that we ever thought enough of education and ever understood its significance to our economic future enough to commit ourselves to national performance goals,” Bush said at the close of the summit. “And this is the first time a president and governors have ever stood before the American people and said ... we expect to be held personally accountable for the progress we make in moving this country to a brighter future.”

Before the president could announce those goals at his 1990 State of the Union address, much work remained to be done.

Christopher T. Cross, who served as an assistant secretary of education under Bush, writes in his book Political Education: National Policy Comes of Age that weeks of “often rancorous” meetings were held in the White House office of Porter, with Clinton never missing a meeting.

The goals were highly aspirational, policymakers agreed, and despite the creation of a National Education Goals Panel to work toward their fulfillment, “there was no coherent plan for how to achieve the goals,” Cross writes.

In 1990, Bush pushed Cavazos out the door and soon nominated Alexander as secretary of education. Even before he was confirmed, Alexander had helped develop a presidential initiative called America 2000, a mixed-bag program calling for higher standards, a new voluntary national system of achievement tests, and a nonprofit New American 69��ý Development Corporation, which would stage design competitions for innovative schools, with a plan for one in each congressional district.

Chester E. Finn Jr., an assistant secretary of education under Reagan, writes in his memoir Troublemaker: A Personal History of School Reform Since Sputnik, that he accompanied Alexander to the White House to vet the proposal with aides and eventually with the president himself.

“This is the best thing I’ve ever seen,” Bush said, according to Finn. The initiative was launched, though Congress was uninterested in the elements that required legislative approval.

“Truth be told, Bush and Alexander didn’t work Capitol Hill very hard on behalf of America 2000,” Finn writes.

The ADA and Supreme Court Picks

There were other areas where Bush’s time as president made a lasting impact on the nation’s schools. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, which gave schools additional responsibilities for serving students and adults with disabilities.

And Bush filled two vacancies on the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice David H. Souter, who succeeded Justice William J. Brennan Jr. in 1990, disappointed some of Bush’s supporters by turning out more liberal than they had hoped. Souter, who retired in 2009, was a strong supporter of strict separation of church and state in cases about school prayers and religious school vouchers.

In 1991, Bush nominated Clarence Thomas to succeed Thurgood Marshall, the first African-American on the high court and the architect of the legal strategy to undo legal segregation in public education. Few believed Bush’s insistence that Thomas, a federal appeals court judge and former Reagan administration official, was the “best qualified” candidate for the opening.

Thomas, who became the longest-serving current justice upon the retirement of Justice Anthony M. Kennedy this summer, has been a reliably conservative vote for allowance of student prayers in public schools and for eliminating the consideration of race in education. He has written many iconoclastic opinions expressing his views about how students have limited rights in public schools.

While Bush’s role on the international stage, presiding over the end of the Cold War and leading an international coalition of countries against Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, led to a rise in the polls, a souring of the economy late in his term created political difficulties. Clinton, who had worked so closely with Bush and his White House on education matters, did not hesitate to criticize the president as he sought the Democratic nomination.

“I think we need a real education President,” said in a campaign speech in January 1992. “We need more than ‘photo ops’ at schools, and rhetoric, and telling other people what to do.”

Bush, in his re-election campaign, amped up his support for school choice that included the possibility of the use of vouchers at private schools, including religious schools.

An October 1992 presidential debate among Bush, Clinton, and independent candidate H. Ross Perot, at the University of Richmond, highlighted the president’s education themes, as well as his distinctive speaking style.

The nation cannot improve its schools and create better jobs by doing it “the old way,” Bush said. “You can’t do it with the school bureaucracy controlling everything. And that’s why we have a new program that I hope people have heard about. It’s being worked now in 1,700 communities—bypassed Congress on this one, Ross—1,700 communities across the country. It’s called America 2000. And it literally says to the communities: Reinvent the schools. Not just the bricks and mortar, but the curriculum and everything else. Think anew.”

Bush added that he believed “that we’ve got to get the power in the hands of the teacher, not the teachers’ union. ... And so our America 2000 program also says this. It says let’s give parents the choice of a ... public, private or religious school. And it works. It works in Milwaukee. Democratic woman up there taken the lead in this—the mayor up there—on the program. And the schools that are not chosen are improved; competition does that.”

Clinton won the 1992 election with 43 percent of the popular vote, to just over 37 percent for Bush and nearly 19 percent for Perot.

Clinton continued the push for national standards, with the 1994 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, moving the federal government farther into standards and testing.

Bush would go on to see his son George W. Bush succeed Clinton and oversee another reauthorization of the main K-12 education law, this time under the name the No Child Left Behind Act, which put the federal government front and center in ensuring that assessments and federally mandated school improvement remedies were a feature of every state’s accountability system.