Controversies regarding religion in the classroom in the United States are as old as the public school system itself. Most recently, a Louisiana law mandates that posters of the Ten Commandments be hung in every classroom in the state, while in Oklahoma, the state government has mandated that the Bible be taught to all public school students.

Whether these two policies are violations of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment establishment clause will be litigated in the courts in short order. Ultimately, these particular laws will be judged based on the details of how they will be implemented, funded, and enforced on those who refuse or neglect to comply.

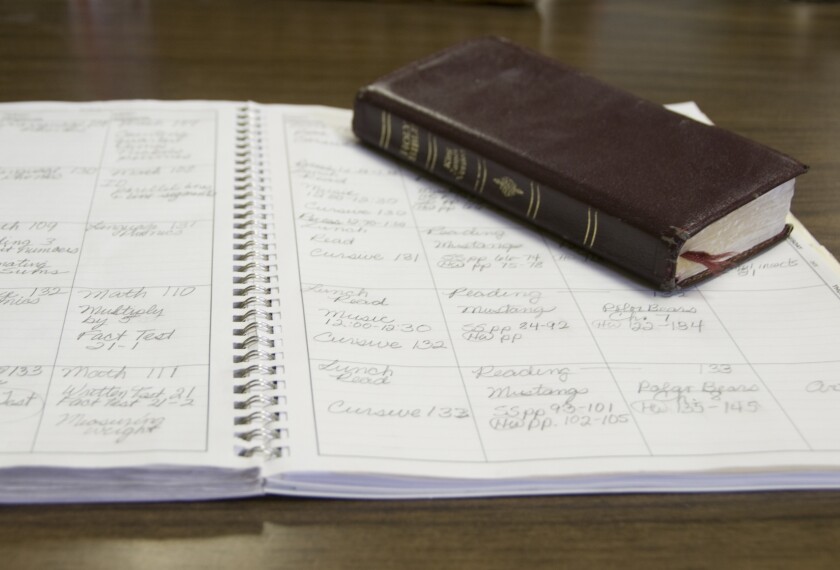

As a public school teacher getting ready to begin my 17th year in the classroom teaching both politics and religion in a politically diverse district, I can say with certainty that both of the religious documents centered by the aforementioned new laws—the Ten Commandments and the Bible—do have a place in public school.

However, I have a few questions for leaders involved in the implementation and enforcement of laws like the ones in Louisiana and Oklahoma.

- Will your students have the opportunity to be exposed to other religious texts such as the Torah, the Quran, the Bhagavad Gita, or the Tripitaka (just to name a few) to compare and contrast their historical and present impact on societies around the world?

- Will your students have the opportunity to learn about other religious codes of ethics, including but not limited to the Five Pillars of Islam, the Mitzvot of Judaism, or the Five Precepts of Buddhism? If you hang the Ten Commandments, will you also hang the others?

- Will your policies also engage students in discussions of why humans are or are not religious at all? Will you make all students, even the nonreligious ones, feel welcome to learn in your schools?

I am all for policies that answer these questions in an inclusive way and that empower students by leading them to ask and answer big questions about religion and its impact on all of us. How can students leave our schools knowing about the world if they don’t study religion in school? How can they collaborate with their neighbors and colleagues to build stronger communities and democracies when they don’t know what others value?

Some have argued that the policies in Louisiana and Oklahoma and any others like them should be rejected on their face because they violate the spirit of secularism expressed by Thomas Jefferson in his Letter to the Danbury Baptists in 1802. In that letter, Jefferson wrote the now-famous phrase “a wall of separation between church and state,” which has been a rallying cry for those concerned about religious liberty and whose sentiments have been reified by multiple U.S. Supreme Court rulings throughout American history.

This has brought many to the conclusion that religion has no place in public schools. In fact, every year I hear some questions from my colleagues and students wondering if my high school course, called Religion and Society, is a violation of Jefferson’s vision and the Constitution.

This is an understandable point of view, but religion and school are not antithetical to each other. From a historical perspective, in fact, religion and education have been inextricably linked in the United States. Religion taught academically at the K-12 level is not only legal but essential.

Many states currently have standards that include explicit instruction in the history of religion in America and around the world including the history and social science framework in my home state of California where the word “religion” is mentioned a couple hundred times. Religion is a mover of history, and it influences our politics every day. Omitting the study of religion from social studies education is malpractice.

For nearly two decades, I have witnessed firsthand the tremendous impact that a deep and diverse study of religion has had on my students. Religious studies courses should be an essential part of any comprehensive public school education. My students have developed into compassionate scholars and citizens because of their engagement with diverse religious perspectives. I hope that all students in the United States will have the same opportunity someday.

Some might say that religion can be done at home, and that is true in a limited sense, but religion at home tends to focus on one religious perspective only, which eliminates the opportunity for kids to grow as citizens in a pluralistic society.

One of the many purposes of our education system is to prepare our students for citizenship in a diverse community. We must lead students to read critically and think deeply about ideas that they agree with and disagree with. These exercises are essential for the development of student intellect and identity.

Engaging in criticality about historical and ethical ideas like the ones presented in the Ten Commandments and the Christian Bible is essential for preparing our students for an adult life where they will live, work, and vote alongside people with different views. However, when the study of religions is uncritical and monocultural, we lose the citizenship mission of public education.