(This is the first post in a four-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What are your recommendations for how best to set up and organize small groups in classroom instruction?

Many teachers find that well-organized student small-group work facilitates learning and effective classroom management.

It’s the “well-organized” part that can trip many of us up, though.

This four-part series will share “tried-and-true” strategies for maximizing the effectiveness of this kind of instruction.

Today, Valentina Gonzalez, Olivia Montero Petraglia, Jenny Vo, and Jennifer Mitchell provide their suggestions.

You might also be interested in a previous series on small-group instruction, as well as .

‘Teach the Routine’

Valentina Gonzalez is a former classroom teacher with over 20 years in education serving also as a district facilitator for English-learners, a professional-development specialist for ELs, and as an educational consultant. She is the co-author of 69��ý & Writing with English Learners and works with teachers of ELs to support language and literacy instruction. Her work can be found on and on . You can reach her through her or on Twitter :

Image by Valentina Gonzalez

I didn’t learn overnight how to make small-group instruction work for my students and for me. When I taught mainstream language arts (reading and writing in elementary school), we planned together as a team. Planning went very quickly because the more experienced teachers would bring their lesson plans from previous years and tell us “newbies” what we would be teaching. We all taught the same thing and mostly the same way.

It quickly became clear that teaching in a whole-group setting wasn’t meeting the needs of all my students. Some students breezed through what I taught because they already knew it. Others had no idea what just happened. And most of the time I felt like students did not understand their role in learning. We were all just going through motions.

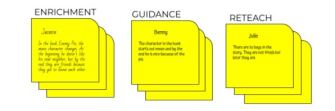

It wasn’t long before small-group instruction organically formed in my classroom. After teaching a whole-group lesson and formatively assessing, I divided the class. For example, at the end of a lesson. I asked students to write a ticket out or gave them five questions to answer on a sticky note. Based on their answers, I quickly formed three groups for our next lesson; one for Enrichment, one for Guidance, and one for Reteach.

Image by Valentina Gonzalez

Over the next couple of days, during independent reading, I gathered students in these small groups to conduct a on the topic. It was not perfect, but I could tell that my students were beginning to grow rather than flounder or become bored.

Here’s what I learned along the way.

1. Teach the routine.

This is make or break. If students understand what small-group time is going to look and sound like, they will be more successful with it. Before you begin implementing small groups, hold a lesson with students telling them what small groups are and why you are doing them. If possible, model for the class what a small group will look like AND what the rest of the class will be doing. By teaching the routine, you set students up for success. On the other hand, if you don’t teach the routine, don’t be disappointed if while you are working with your small group the remainder of the class is off task. Clarity is key!

A few things to teach students about the routine are:

- the time frame for instruction

- what you expect from the time

- the acceptable noise level

- how students can move about

- when it’s acceptable to interrupt the small group

- how to interrupt the small group

2. Teach students what to do independently.

It’s possible that one of the biggest reasons why some teachers abandon small groups is because they become frustrated when they feel they’ve lost control of the classroom. To avoid this, clarity in goals and expectations for the end result is a must. Be as explicit as possible with instructions before sending students off to work on their own.

Tips for teaching students what to do independently:

- write out the goals on chart paper or under a document camera and keep them visible during the lesson

- show examples and nonexamples of end products if applicable

- give options/choice

Keep in mind that while you work with small groups, the rest of the class can be working on various learning tasks. In primary grades, some teachers implement “centers” or “rotations” while gathering small groups. These can be described as short and interesting learning activities that students move through tied to previously learned skills. Older students can be reading or writing independently, working on research, problem solving, experimenting, or more!

3. Keep groups fluid.

These are your small groups. As Penny Kittle says, “Follow the child.” Don’t get too firm about them. Do what students need and keep flexibility alive. Today, “Jasmin” may be in the enrichment group but next week, she may need reteaching when we move to another topic. Small groups are fluid. They move and change with the time, topic, and needs of the learners.

There are so many reasons to hold small groups. Your small groups might include:

- strategy lessons in reading/writing/math

- /writing

- phonics review

- reteaching/preteaching/enrichment (any subject)

- reading/writing/math

- language development

Small groups are commonly seen in reading, but small-group instruction is useful cross-curricularly. The nature of a small group lends itself to a smaller student-teacher ratio allowing for students to share responses more frequently than in large-group settings. Teachers can use this time to gauge understanding, provide timely feedback, take anecdotal notes, and build stronger relationships with students. benefit greatly from small group instruction with their teachers and peers.

‘Practice, Practice, Practice’

Olivia Montero Petraglia began her teaching career as an upper-primary bilingual teacher in San Diego. Over the last 23 years, she has served in leadership, as an instructional coach, language-acquisition specialist, consultant, and teacher in international schools in Colombia, Thailand, Indonesia, and Laos:

To be fully present and have quality instructional time with small groups of students is golden. While we all know what the research says about the positive impact of small-group instruction, it can be challenging to set up and manage.

Something I wished I would have understood earlier in my teaching career is that setting small-group work is a process that requires an investment in time and a collaborative classroom-community effort. A carefully co-crafted approach can transform small-group work into much more than just ideal conditions for differentiated instruction. It is also a great way to build community and help students develop skills such as self management, time management, and independence. Dedicating two to three weeks at the start of the school year to learn about your students while practicing different aspects of small-group work routines will gain you lots of mileage throughout the remaining school year.

Grouping students

When I start the year, I usually plan heterogeneous groups to work through fun, low-stakes activities. This allows me to notice several learning behaviors at a time. By keeping these initial sessions short (8 -12 minutes), valuable data can be collected quickly and minimize the pressure to form “perfect” groups straight away. What you notice from each day’s session will help you regroup students and identify learning objectives for upcoming sessions. As the weeks go by, you will have opportunities to triangulate a range of data to inform different groupings and learning objectives linked to the curriculum; however, you will have had the opportunity to establish dispositions and a sense of community that will help support small-group work for the duration of the school year.

Invite students into the process

Be explicit when sharing the “why” for small-group work. A simple, yet critical initial exercise is to facilitate a circle-time discussion about small-group work. As students share their ideas, record responses on chart paper so that you can refer back to their plan as needed throughout the year.

- What good things can happen as a result of small-group learning opportunities?

- What things might get in the way of quality group work and what can help us to have the best small-group learning opportunities?

Visual guides

Create anchor charts or digital slides to display bullet point steps for each session. If a student is not sure of what to do after you have provided instructions or a mini-lesson, instead of telling them, point to the visual. Over time, you will condition students to reference the visual instead of asking you. For younger students, you can use numbered images as reminders. This one simple step can be such a game changer.

Prepare checklists

Create a spreadsheet for yourself of weekly or daily “look fors” to make it easy to record quick notes and keep you focused on key data. This also helps keep track of how frequently you meet with students.

Practice, practice, practice:

Think Vygotsky’s “i + 1.” Introduce different aspects of small-group work one step at a time. For example, to start, provide the whole class with an independent activity that will keep them engaged for the duration of the time needed for you to meet with one or two small groups. As students begin to understand expectations and routines, gradually add more complexity to the dynamics of small-group work sessions.

- Discuss and post a “What to do when I‘m done” list ahead of time that includes low prep activities such as independent reading, journal writing, or practice for skills previously learned. No need for students to ever be off task even when they finish work.

- Debrief at the end of every small-group practice session. Prompt students to offer feedback for feed forward for improvement during the next session. Celebrate successes and name what students are getting right, and you are more likely to see it again and again.

- Use music as a scaffold for transitioning. Starting a two- or three-minute song can cue students to move around, gather needed materials, get to their learning spaces, check in with others, and aim to be ready by the end of a song. Resist giving instructions; let the music do the work. Keep practicing until everyone knows what to do. Kids love this, and with carefully selected music, it can also be a mood changer.

I used to think that I couldn’t start small-group work until I had time to get to know my students better. Now I understand that there is no better way to get to know students than engaging with them. Small-group interactions make it possible to take careful note of students’ learning behaviors, strengths, and academic gaps.

‘Flexible & Differentiated Learning’

Jenny Vo earned her B.A. in English from Rice University and her M.Ed. in educational leadership from Lamar University. She has worked with English-learners during all of her 26 years in education and is currently the Houston area EL coordinator for International Leadership of Texas. Jenny proudly serves as the president of TexTESOL IV and works to advocate for all English-learners. She loves learning from her #PLN on Twitter so feel free to follow her @JennyVo15.

What is small-group instruction? Small-group instruction is when you teach the students in small groups ranging from 2-6 students. It usually follows whole-group instruction. There are many benefits of small-group instruction. It is effective because the teaching is focused on the needs of the students, with the goal of growing their academic skills.

Small-group instruction provides opportunities for flexible and differentiated learning. With the smaller number of students, students have more chances to participate. Teachers are able to monitor the students better, thus providing better and more individualized feedback and support. Small-group instruction can be used in all content classes and is beneficial for students of all levels.

How do you best set up and organize small groups? There are a variety of ways you can set up and organize small groups. How you do it depends on your objective and goal for the lesson or activity. Some ways you can group students include: by ability, strategy, expert/interest groups, cooperative tasks, and student choice The three setups I use the most are by ability, by strategy/skill, and by interest.

Grouping by ability: You can group your students by ability, such as by reading level or language-proficiency level. Having students of the same ability in the same group will allow the teacher to provide lessons and activities that are more focused and targeted to the needs of the students at that level. There is less pressure because the students know that they are on the same playing ground as the other group members. For English-learners at that same level, they will feel less intimidated to take chances to speak.

Grouping by strategy/skill: Strategy groups are great when you want to provide instruction on a specific skill or strategy. Let’s say you gave an assessment. Looking at the data from the assessment, you see that certain students need more instruction and practice with a certain skill or strategy. Instead of reteaching the whole class, you can group together students based on the skill they need to work on. You can have reading groups working on inferencing, main idea, or summary. You can have math groups working on multistep problems, graphing, or data analysis. Your science groups can be working on food chains/webs, force and motion, or adaptation. Strategy groups very much rely on data. Groups should be short term and should be very fluid.

Expert/interest groups: Grouping students by subject knowledge or interest is a great way to work with small groups for projects. These types of small groups are perfect for science and social studies classes. Because students are grouped based on areas of interests, they consist of students of varying ability levels. With these groups, it is best that there is a cooperative grouping structure where roles are assigned so that responsibilities are equally divided. In that way, one or two students are not doing all the work or taking over the project and not letting the others be involved. English-learners can benefit from being in this type of group because they can share their knowledge since they may know more about the topic than the other members. It also gives them opportunities to improve their language by hearing more advanced students speak.

What are the other students doing while I’m in small-group instruction? I hear this question a lot when there is discussion about implementing small groups. My answer is: They should be working on activities that you have planned where they can work by themselves, with a partner, or in a small group that will allow you to focus on the group you are working with. For the language arts block, they can be reading and responding to their reading independently or working on their writing. For math, you can set up different workstations with activities focusing on different skills for review. Workstations can also be used for science and social studies class. Giving students a menu of activities to choose from is also a very effective way to keep the rest of the class engaged while you do small groups.

If you have not implemented small-group instruction in your classroom, I encourage you to try it. You will come to see the benefits to the students with your own eyes. With anything new, do it in small steps. Try one way of grouping. Try it once a week and slowly add more time. It is a great instructional approach to add to your teaching toolbox!

Student Leadership

Jennifer Mitchell teaches ELs in Dublin, Ohio. Connect with her on Twitter: or on her :

The myriad benefits of partner and group work are clear (particularly for ELs), but a system of purposeful, long-term groups with student leaders can transform classroom culture. Leading groups of 3-5 classmates for a quarter, semester, or year, my “squad leaders” (a structure and term I borrowed from my years in marching band) start group discussions and keep them going, remind their squad members about materials and on-task work as necessary, and, perhaps most importantly, build our community by demonstrating genuine caring for their squad members. As role models for their classmates, these leaders challenge themselves not just to grow academically but also to step out of their comfort zones and hone their leadership skills.

I encourage them to use purposeful small talk and tap into identity-related assignments, just as I do as a teacher, to forge strong connections. They also serve as points of contact between me and their classmates, providing clarification or help to their squad members when possible, notifying me of any concerns, and even pointing out when their squad members excel.

Choosing leaders:

The success of this structure hinges on the effectiveness and buy-in of the squad leaders. It’s tempting to choose students who are academically (or linguistically) strong and/or socially popular, and while these can be great characteristics in a leader, they are not as important as the student’s desire to improve the classroom culture and grow personally. In fact, it’s students who care deeply for others and/or have the personal drive to challenge themselves who are most likely to become effective squad leaders.

Through careful observation during the first month of school, I can usually pick out a few students in each class who will be my leaders. It’s so essential to have the right students that if I can’t identify at least a couple strong leaders in a given class, I do not move forward with implementation. I’ve tried and failed to push students who weren’t ready, and the whole structure loses credibility too quickly. It’s better to stick with typical groups (possibly implementing squads later) than to end up with a class that will never buy into the vision because they’ve seen it fail with leaders who didn’t follow through. (For this reason, it’s essential to put careful work into supporting and developing your leaders throughout the year!)

Once I have my leaders in mind, I share my vision for squads with the whole class and invite anyone who is interested to complete an . I want everyone to feel they had the opportunity, and it’s interesting to see who applies. After the application has been posted for a couple days, I talk individually with any leaders I’d identified who haven’t applied yet. It’s incredible to see the light in a student’s eyes upon hearing that I want them to be a leader. In fact, some of my best leaders were students who initially doubted their own leadership ability and needed encouragement to take on the role, but their determination and love for others drove them to have a real impact.

Implementation:

Once I select the leaders, I invite them to a special meeting to introduce the role in more detail, and each leader reflects and sets goals based on their application responses. Next, it’s important to discuss the vision of the squad structure with the whole class before seating them with their new squads. I share how powerful this structure was for me and my friends in marching band in terms of personal growth, group excellence, and social-emotional support. Then we split into squads for community-building activities, and from then on, the squads are together for nearly everything. They collaborate, share and reflect on their work together, engage in discussions, and participate in deeper connection-building activities with the squad leaders serving as the glue that binds each group ever more closely. Frequent leader meetings, conferring, and mini-tasks challenge leaders to reflect and problem-solve. Within a classroom culture built around reflection and goal-setting, a focus on learning, and SEL, the squads grow into supportive communities that provide a stronger sense of purpose and belonging in our classroom.

Thanks to Valentina, Olivia, Jenny, and Jennifer for contributing their thoughts.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones are not yet available). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first 10 years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- The 11 Most Popular Classroom Q&A Posts of the Year

- Race & Racism in 69��ý

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Challenging Normative Gender Culture in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech With 69��ý

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in 69��ý

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- 69��ý Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Assessment

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in 69��ý

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a .